Retour au texte original en français : Lisières

Edges – Fringes – Margins

Collage

On April 26, 2019 a meeting took place in Lyon between György Kurtag (composer and improvisator visiting from Bordeaux), Yves Favier (then technical director at ENSATT in Lyon), and the members of the PaaLabRes collective, Jean-Charles François, Gilles Laval and Nicolas Sidoroff. The format of this meeting was to alternate moments of musical improvisation with discussions about the different participants’ backgrounds.

Following this meeting, we decided to develop a kind of “cadavre exquis” [game of consequences] around the concept of “edges”, each of the participants writing more or less fragmented texts in reaction to the writings that were accumulating little by little. In addition, the five people were also allowed to propose quotations from various authors in connection with this idea of edges, fringes or margins. It is this process that gave rise in the Grand Collage (the river) of this edition “Faire tomber les murs” to 10 collages (L.1 – L.10) of these texts accompanied by music, recorded voices and images, with in particular extracts from the recording of our improvisations made during the meeting of April 26, 2019. You will find below all the texts.

Direct access to the texts of the authors included in the collage:

experiencespoetiques

Définitions 1 Définitions 2 Définitions 3

Aleks A. Dupraz 1 Aleks A. Dupraz 2

Yves Favier 1 Yves Favier 2 Yves Favier 3 Yves Favier 4 Yves Favier 5

Gustave Flaubert

Jean-Charles François 1 Jean-Charles François 2 Jean-Charles François 3

Edouard Glissant 1 Edouard Glissant 2 Edouard Glissant 3 Edouard Glissant 4

Emmanuel Hocquard 1 Emmanuel Hocquard 2

Tom Ingold 1 Tom Ingold 2

György Kurtag 1 György Kurtag 2

François Laplantine et Alexis Nouss 1 François Laplantine et Alexis Nouss 2

Gilles Laval

Michel Lebreton 1 Michel Lebreton 2

Jean-Luc Nancy

Nicolas Sidoroff 1 Nicolas Sidoroff 2 Nicolas Sidoroff 3 Nicolas Sidoroff 4

Dominique Sorrente

Emmanuel Hocquard :

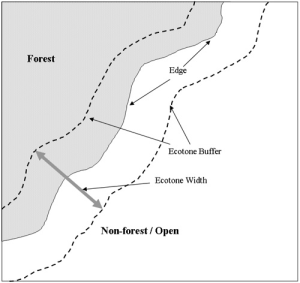

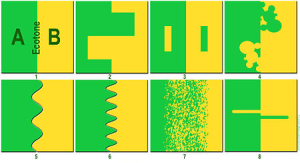

The edge is a strip, a list, a margin (not a line) between two milieus of different nature, which have something of the nature of two entities without being confused with any of them. The edge has its own life, its autonomy, its specificity, its fauna, flora, etc. The edge of a forest, the fringe between sea and land (estran), a hedge, etc.

dans la cour platanes cinq

dans la cour platanes cinq

dans la cour platanes cinq

(Le cours de Pise, Paris : P.O.L., 2018, p. 61)

Yves Favier :

Evidently the notion of “Edge” or “Fringe” is the one that tickles the most (the best?) especially when it is determined as an « autonomous zone between 2 territories », moving and indeterminate musical zones, yet identifiable.

They are not for me “no man’s (women’s) land”, but rather transition zones between two (or more) environments…

In ecology, these singular zones are called “ecotones”, zones that shelter both species and communities of the different environments that border them, but also particular communities that are specific to them. (Here we touch on two concepts: Guattari’s “Ecosophy”, where everything holds together, and Deleuze’s “Hecceity = Event.”

Définitions : Lisières – subst. fém.

Étymol. et Hist. 1. 1244 « bord qui limite de chaque côté d’une pièce d’étoffe » (Doc. ds Fagniez t. 1, p. 151); 2. a) 1521 « frontière d’un pays » (Doc. ds Papiers d’État de Granvelle, t. 1, p. 185); b) 1606 « bord d’un terrain » (Nicot); c) 1767-68 fig. « ce qui est à la limite de quelque chose » (Diderot, Salon de 1767, p. 195); 3. a) 1680 « bandes attachées au vêtement d’un enfant pour le soutenir quand il commence à marcher » (Rich.); b) 1752 mener (qqn) par la lisière « conduire (quelqu’un) comme on mène un enfant » (Trév.); c) 1798 mener (qqn) en lisière « exercer une tutelle sur (quelqu’un) » (Ac.); 1829 tenir en lisière « id. » (M. de Guérin, loc. cit.); 4. 1830 chaussons de lisière (La Mode, janv. ds Quem. DDL t. 16). Orig. incertaine. Peut-être dér. de l’a. b. frq. *lisa « ornière », que l’on suppose d’apr. le lituanien lysẽ « plate-bande (d’un jardin) » et l’a. prussien lyso « id. (d’un champ) ». Cette forme *lisa a dû exister à côté de l’a. b. frq. *laiso, de la même famille que l’all. Gleis, Geleise « voie ferrée, ornière »; cf. a. h. all. waganleisa « ornière »; cf. aussi le norm. alise « ornière »; alisée « id. » (v. REW et FEW t. 16, p. 468b). L’hyp. du FEW t. 5, pp. 313b-314a, qui dérive lisière du subst. masc. lis (du lat. licium « lisière d’étoffe »), est peu probable, ce dernier étant plus récent que lisière (1380, « grosses dents aux extrémités d’un peigne de tisserand », Ordonnances des rois de France, t. 6, p. 473, v. aussi note b; puis, au xviiies., au sens de « lisière d’une étoffe », v. FEW t. 5, p. 312b).

http://www.cnrtl.fr/etymologie/lisi%C3%A8re

György Kurtag:

[He quotes here Pr. André Haynal, psychiatrist, psychanalyst, emeritus professor at Genève University, concerning the book by Daniel N. Stern, Le moment présent en psychothérapie : un monde dans un grain de sable, Paris: Éditions Odile Jacob, 2003.

https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-carnet-psy-2004-2-page-11.htm]

“More spectacular is the emergence of ‘urgent moments’ that produce ‘moments of encounter’.

Stern emphasizes experience and not meaning, although the latter, and thus the dimension of language, plays an important role. For him, present moments occur in parallel with the language exchange during the séance. The two reinforce and influence each other in turn. The importance of language and explicitness is therefore not called into question, although Stern wants to focus on direct and implicit experience.”

Yves Favier:

These edges between meadow, lake and forest are home to prairie species that prefer darker and cooler environments, others more aquatic ones, and forest species that prefer light and warmth.

Isn’t this the case in improvisation?…

Aleks Dupraz:

In my writings, the notion of “edge” or “fringe” is gradually replacing that of “margin”, which is very much used by sociology and is frequent in the alternative spheres of art and politics. Even though we know that “the margin” is always in interaction – if only in the imaginary – with its opposite (the center where the centrifugal force of norms may seem at its highest level, which seems debatable insofar as the proximity of power places also confers a certain freedom as to the application, alteration and production of norms), the notion of “edge” carries within it the possibility of another displacement that is no longer simply that of the relationship between “a center” and “its periphery”. Being on the edge of the University is already being on the frontier of other worlds, and perhaps this opens up possibilities for me to think about my life experience and my approach differently than through the sole prism of the tension at work in a process of identity construction that would relate mainly to the university institution and its norms.

experiencespoetiques | lisière(s)

François Laplantine and Alexis Nouss:

The thought of the between and the in-between is linked to crossbreeding, because attention to the interstice makes us realize that we cannot be both at the same time but alternatively, as in Frenando Pessoa’s heteronymic process or as in the steps of the tango. (…) The in-between is what we cannot place border to border or put end-to-end and which prevents us from following the groove. It is a gap that cannot be filled, or at least cannot be filled immediately, but which calls for mediations that, as with Adorno, should be opposed to reconciliation and also to the notion of work of art insofar as the latter claims to reach a completion.

Métissages, de Arcimboldo à Zombi. Montréal, Pauvert, 2001.

Michel Lebreton:

The edges are the places of what is possible. Their limits are only defined by the environments bordering them. They are shifting, subject to erosion and sedimentation: there is nothing obvious about them.

(See in the present edition paalabres.org the « house » of M. Lebreton).

Yves Favier :

1/ Would the improviser be this particular “being on the alert”?

Hunter/gatherer always ready to collect (capture?) existing SOUNDS, but also “herder”, in order to let those “immanent” ones emerge? Not yet manifest but already “possible in in the making”?…

2/ “the territory is only valid in relation to a movement by which one leaves it.” In the case of the notion of Hocquard’s Border associated with the Classical political conception, the improviser would be a transmitter between 2 territories determined in advance to be academic by convention: a transmitter between THE contemporary (sacred art) music and THE spontaneous (social prosaic) music…we’ll say that it’s a good start, but which will have no development other than in and through conventions…it will always be a line that separates, it’s an “abstraction” from which concrete bodies (including the public) are de facto excluded.

3/ What (musical) LINE, could mark as Limit, an “extremity” (also abstract) to a music so-called “free” only to be considered from the inside (supposedly from the inside of the improviser).

Effectively taking away any possibility of breaking out of these identity limits (“improvisation is this and no other thing”, “leave Improvisation to the improvisers”) comes from the fantasy of the creative origins and its isolated « geniuses ». … for me the « no man’s land » suggested by Hocquard can be found here!

Nicolas Sidoroff :

Emmanuel Hocquard distinguishes three conceptions of translation with regard to the limit (the “reactionary conception” where translation can only betray), to the border (the “classical conception” where translation passes from one language and culture to another), and to the edge (a conception that “makes translation […] a hedge between the fields of literature”).

(Emmanuel Hocquart, Ma haie : Un privé à Tanger II, Paris : P.O.L., 2001, pp. 525-526.)

I work on the notions of “border” and “edge” between different activities. (…) A border is crossed in the thick and consistent sense of the term, one part of the body then the other, more or less gradually. This body has a thickness, we are on one side and on the other of a line or a surface which constitutes a border at a given moment. This can create a swing, such as back and forth movements in body weight above that line or on either side of a line or surface which constitutes a border at a given moment. How do you cross a border between several activities: what happens when I change “caps,” for example, between a space-time where I am a composer and another where I am a sound engineer?

(Nicolas Sidoroff, « Faire quelque chose avec ça que je voudrais tant penser, faisons quelque chose avec ça, de ci, de là », Agencements N°1, mai 2018, Éditions du commun, p. 50)

Dominique Sorrente :

For a long time, I’ve lived on the edge of the world.

experiencepoetiques

From one edge to the other, our movements form a song of echoes, a forest of signs in the sky.

Ecological corridor :

An ecological corridor [corridor], as distinct from a biological corridor [corridor biologique] and from the ecological continuum [continuum écologique]], is a functional passage zone, for a group of species belonging to the same milieu [espèces inféodées] ], between several natural spaces. This corridor thus connects different populations and favors the dissemination and migration of species, as well as the recolonization of disturbed environments.

For example, a footbridge [passerelle] that overlooks a highway and connects two forest massifs constitutes an ecological corridor. It allows fauna [faune] and flora to circulate between the two massifs despite the almost impermeable obstacle represented by the highway. This is why this footbridge is called a wildlife passage.

Ecological corridors are an essential component of biodiversity conservation [biodiversité] and ecosystem functioning [écosystèmes]. Without their connectivity, a very large number of species would not have all the habitats necessary for their life cycles (reproduction, growth, refuge, etc.) and would be condemned to extinction in the near future.

Moreover, exchanges between environments are a major factor of resilience [résilience]. They allow a damaged environment (fire, flooding, etc.) to be quickly recolonized by species from the surrounding environment.

Taken as a whole, the ecological corridors and the environments they connect form an ecological continuum for this type of environment and the species that depend on it.

It is for these reasons that current biodiversity conservation strategies emphasize exchanges between environments and no longer focus solely on the creation of sanctuaries that are preserved but closed and isolated.

https://www.futura-sciences.com/planete/definitions/developpement-durable-corridor-ecologique-6418/

Michel Lebreton :

Will the teacher leave the barriers open to wandering and tinkering? Or will he confine all practices to the enclosure he has built over time?

Edouard Glissant :

(…) where the migrant people from Europe (…) arrive [in America] with their songs, their family traditions, their tools, the image of their god, etc., the Africans arrive stripped of everything, of all possibilities, and even stripped of their language. For the den of the slave ship is the place and the time when African languages disappear, because people who spoke the same language were never put together in the slave ship, just like on the plantations. The beings were stripped of all sorts of elements of their daily life, and especially of their language.

(Introduction à une poétique du divers, Paris : Gallimard, 1996, p . 16)

Emmanuel Hocquard :

Everything that concerns margins (marginalia), crossroads, residual spaces or wastelands is to be attached to the edges…

The edges are the only spaces that escape the rules set by the State grammarians, the Versailles gardeners and international town planners.

(Op. cit. p. 62)

Edouard Glissant :

What happens to this migrant? He recomposes by traces a language and arts that could be said to be valid for everyone. (…) The deported African has not had the opportunity to maintain these kinds of punctual legacies. But he did something unpredictable on the basis of the only powers of memory, that is, of the only thoughts of the trace that were left to him: he composed, on the one hand, Creole languages and, on the other hand, art forms that were valid for all. (…) If this Neo-American does not sing African songs from two or three centuries ago, he is re-establishing in the Caribbean, Brazil and North America, through the thought of the trace, the art forms that he proposes as valid for all. The thought of the trace seems to me to be a new dimension of what must be opposed in the current situation of the world to what I call the thoughts of the system or systems of thought. The thoughts of the system or systems of thought were prodigiously fruitful and prodigiously conquering and prodigiously deadly. The thought of the trace is the most valid today to affix to the false universality of the thoughts of the system.

(Op. cit., p.17)

Jean-Charles François :

The wonderful “lisières” [edges, fringes, margins], the wonderful “lisières”, the wonderful “lisières”

The wonderful “lisières”, the wonderful “lisières” and… the nasty “lisier” [manure].

The wonderful “lisières” and the nasty “lisier”

The rebel “lisières” and in the middle of the field the “lisier”.

The “lisières”, the “lisières”, the “lisier”.

The beautiful “lisières” and the nasty “lisier”.

The “lisier” responsible for the beautiful green algae of northern Finistère [in Brittany], which decompose into nasty toxic elements dangerous to humans.

The beautiful “lisières” and the nasty “lisier”.

The mystery of the “lisières”, the great misery of the “lisier”.

The feast of the merry leeways, the feat of the mingled leaflets.

The flux of the winding river, the fever of the weak-link leaser.

The severe inklings of the pollster, the never-ending undulating of the roller-coaster.

The folly of the spending waist and the olive-green of peace on earth.

The beautiful “lisières” and the nasty “lisier”.

The “lisier” is used to define the nasty space of artichokes, between the beautiful “lisières” as nasty result of a beautiful industrial production and nasty ferment of a production of the same kind of beauty.

Being on the alert, entre-capture, being on advert, entre-rapture, being that asserts, prey that lets itself be captured, being-aggressor, enter raptors we get along well, being-a-Grecian, Kairos, intense moment of interaction, being-a-gracious…

The “lisier” is a nasty nose aggressor, while the polished “lisière” agrees to read the parking meters.

The perking masters of the church of the Most Holy Therese of Lisière get bogged down in agreeing with the prosaic Guest-State-Police-Lisier.

The Eldorado of the beautiful Gluierphosate grid fills clysteres in the back pockets of filthy sires linked to their glycemic-prostatic swellings.

The beautiful “lisières” and the nasty “lisier”.

How to get out of the “lisières” and into the space of the “lisier”?

This seems to be the problem of improvisation. The ideal of communication belongs to the “lisières”, the edges, but the content itself remains in the incommunicability of the “lisier”, the slurry (apart from its stench). If the definition of the origin of the sounds at the time of the improvised performance on stage seems to belong to the domain of the unspoken, because it is strictly relevant to the intimacy of each participant, then only the « lisières », the edges of human interactivity, seem to be able to enter the field of reflection. The planning of the sounds, their effective elaboration, appears then to be the exclusive domain of the individual paths. The collective elaboration of the sounds is left to the surprise of the moment of the encounter of personalities who have prepared themselves for it: come what may. Getting stuck in the “lisier” (liquid manure).

However, this is not to say that the “lisières” (edges) of communication between humans do not play an important role in the reflection. In this sense, the question of being on the alert and the meanders of the unconscious /conscious are essential vectors to be taken into consideration. But if improvisation is a collective game, then the elaboration of sounds by individuals on separate paths is no longer sufficient to reflect the collective elaboration of sounds. The problem of the co-construction of sound materials then arises. This is where we fall into the “lisier”. If one prepares the sounds collectively, there is a strong risk of no longer being in the ideal of improvisation, which democratically leaves voices free to express themselves, which accepts the principle – in principle! – of dissension in its midst. But if all those who belong to the club of improvisers have followed the same path before getting on stage, then democracy and dissension on the stage are nothing but a simulacrum, the effects of a theater for a naive audience. Likewise, if those who do not correspond to the idealized sound models of the network are not invited, the agreement among those who are will be almost total. Is the notion of deterritorialization a matter for individuals who meet on neutral ground, or is it the collective elaboration of an unknown terrain? The list of elements of the “lisier” is long. How can we open up this type of research project, both from the point of view of practice and of reflecting on practice?

Nicolas Sidoroff :

Emmanuel describes the edge as: “white stain” [tache blanche]. For a long time, I understood and made him say “white task” [tâche blanche]. The circumflex accent made a lot of sense, evoking both the work to be done (by the task) and a space to be explored characterized by its situation (by the slightly nominalized adjective “white”). Behind this, I understood and still understand, an invitation to come and inhabit, explore and practice such spaces. It evokes the unexplored places of geographical maps, where one could not yet know what to write nor in what colors. The “white stain” is very present in the work of Emmanuel Hocquard. The “white stain translation” for him, a “white stain activity” for me, is to create “unexplored areas (…), it’s gaining ground”. In my vocabulary habits, I would also say: to create the possible.

(« Explorer les lisières d’activité, vers une microsociologie des pratiques (musicales) », Agencements N°2, décembre 2018, Édition du commun, p. 263-264)

François Laplantine et Alexis Nouss :

The zombie or the borderline example of crossbreeding. Both dead and alive, it alone condenses the irreducible and unthinkable paradox of every being. The zombie will never be fully alive, or totally dead. As if the journey of the living to death and the return of the dead to life irretrievably prevented a return to a primary condition. Impossible and vacillating journey, which prohibits any possibility of returning to a point of departure, to a stabilized and recognized identity of social being or moribund being.

(Op. cit.)

Edouard Glissant :

For a very long time, Western wandering – it must always be repeated – for a very long time Western wandering, which has been a wandering of conquests; a wandering of founding territories, has contributed to the realization of what we can call today the “totality-world”. But in today’s space there are more and more internal wanderings, that is to say, more and more projections towards the totality-world and returns to oneself while one is immobile, while one has not moved from one’s place, these forms of wandering often trigger what we call internal exile, that is to say, moments when the imagination or sensitivity are cut off from what’s going on around. (…) And this is one of the givens of chaos-world, that assent to one’s “surroundings” or suffering in one’s “surroundings” are also operative as a way and means of knowing one’s “surroundings”.

(op. cit., p. 88)

Lisière, subst. fém. :

All the dreams had risen, abandoned to their free flight. Servet recounted his impending joy of coming out of the edges. (Estaunié 1896)

I’ll get up at noon: I’ll have cozy mornings in bed. No more studying, no more homework. (Estaunié 1896)

God! I will always have to be pushed and I will always have to be held on the edge and I will languish in eternal childhood. (M. de Guérin, 1829)

Edouard Glissant :

To oversimplify: crossbreeding would be the determinism, and creolization is, in relation to crossbreeding, the producer of the unpredictable. Creolization, it’s the unpredictable. We can predict or determine the crossbreeding, but we cannot predict or determine creolization. The same thinking of ambiguity, which specialists in the chaos sciences point out, at the very basis of their discipline, this same thinking of ambiguity now governs the imaginary of chaos-world and the imaginary of Relationship.

(Ibid. p. 89)

Nicolas Sidoroff :

The expression “edge nucleus” therefore allows, first of all, to radically evacuate representations in rigid boxes with borders or in limiting and excluding boxes. (…) To view musical practices as the interaction and articulation of six “edge nucleus”, each corresponding to a family of activities: creation, performance, mediation-education, research, administration, techniques-instrument making.

(op. cit., p. 265)

https://images.app.goo.gl/F9rWyUQYkWpjJNKF7

Yves Favier :

The notion of “edge” or “fringe” is the one that titillates (best): moving and indetermined yet identifiable musical zones.

Sons-pliés Boltanski

Gilles Laval :

Is there an improvised present, at instantaneous instant T? What are its edges, from the instant to be born or not born, or not-being, the instantaneous not frozen at the instant, right there, hop it’s over! Were you present yesterday at this precise shared but short-lived instant? I don’t want to know, I prefer to do it, with no return, towards the commissures of the senses.

Is improvisation self-deluding? Without other others is it possible/impossible? What target, if target there is?

Instantaneous stinging interpenetrations and projections, agglutinating morphological introspective replicas, turbulent scarlet distant junctions, easy or silly combinations, sharp synchronic, diachronic reactions, skillful oxymoristic fusions and confusions. If blue is the place of the sea, out of the water, it is measured in green, on the edge it is like a rainbow. Superb mass of elusive waves where inside shine and abound edges of gradations, departures with no return, unclear stops, blushing pink blurs, who knows whether to silence, to sight land or say here yes hearsay.

I’ve yes heard the hallali sensitive to the edges of improbreezation, (sometimes gurus with angry desires of grips tumble in slow scales (choose your slope), when others sparkle with unpredictable happy and overexcited surprises). End-to-end, let us invite ourselves to the kairostic heuristic commissures of imagined spaces and meanders, alone or with others, to moredames [pludames], to moreofall [plutoustes].

“commissure: (…) The majority of 19th century and 20th century dictionaries also record the aged use of the term in music to mean: Chord, a harmonic union of sounds where a dissonance is placed between two consonants (DG).”

“The end-to-end principle is a design framework in computer networking.

In networks designed according to this principle, application-specific features reside in the communicating end nodes of the network, rather than in intermediary nodes, such as gateways and routers, that exist to establish the network. In this way, the complexity and intelligence of the network is pushed to its edges.”

(End-to-end principle, Wikipedia)

“Kairos (Ancient Greek: καιρός) is an Ancient Greek word meaning the right, critical, or opportune moment.[1] The ancient Greeks had two words for time: chronos (χρόνος) and kairos. The former refers to chronological or sequential time, while the latter signifies a proper or opportune time for action.” (Kairos, wipikedia)

Kairos is the god of opportune occasion, of right time, as opposed to Chronos who is the god of time.

Jean-Charles François :

The “lisières” (edges) make you dream,

melt into white tears

the mythology of the white stain

is that all the maps are colored

no more of them to make us dream

Yves Favier :

…fluctuating moving data…leaving at no time the possibility of describing a stable/definitive situation…

temporary…valid only momentarily…on the nerve…

to touch the nerve is to touch the edge, the fringe, the margin…

improvisation as rapture…temporal kidnapping…

…where one is no longer quite yourself and finally oneself…

…testing time by gesture combined with form…and vice versa…

the irrational at the edge of well-reasoned frequency physics…

…well-tempered…nothing magical…just a fringe, an edge, reached by nerves…

ecotone…tension BETWEEN…

…between certainties…

…between existing and pre-existing…

immanent attractor…

…between silence and what is possible in the making…

this force that hits the nerve…

…that disturbs silence?…

…the edge, the fringe, the margin as a perpetually moving continuity…

The inclusion of each milieu in the other

Not directly connected to each other

Changing its ecological properties

Very common of milieux interpenetration

Terrier

Termite mound

A place where one changes one’s environment

For its own benefice and for that of other species

What narrative does the edge convey?…

György Kurtag :

[Quote from Pr. André Haynal :]

“In his new book (Daniel N. Stern, Le moment présent en psychothérapie : un monde dans un grain de sable, Paris : Editions Odile Jacob, 2003), Stern talks, as a psychotherapist and observer of daily life, about what he calls the ‘present moment’, what could also be called the blissful moment, during which, all of a sudden, a change can take place. This phenomenon, which the Greeks call kairos, is a moment of intense interaction among those who do not appear without a long prior preparation. This book focuses our attention on the ‘here and now’, the present experience, often lived on a non-verbal and unconscious level. In the first part, the author gives a very subtle description of this ‘now’, the problem of its nature, its temporal architecture and its organization.

In the second part, entitled ‘The contextualization of the present moment’, he talks, among other things, about implicit and intersubjective knowledge.

Implicit <> explicit :

to make the implicit explicit and the unconscious conscious is an important task of psychotherapies of psychoanalytical (for him ‘psychodynamic’) or cognitive inspiration. The therapeutic process leads to moments of encounter and ‘good moments’ particularly conducive to a work of interpretation, or even to a work of verbal clarification. These moments of encounter can precede, lead to or follow the interpretation.

These ideas are obviously inspired by research on implicit non-declarative knowledge and memory on the one hand, and explicit or declarative knowledge and memory on the other. These terms refer to whether or not they can be retrieved, consciously or not. The second therefore concerns a memory system involved in an information process that an individual can consciously retrieve and declare. ‘Procedural memory’, on the other hand, is a type of non-declarative memory, which consists of several separate memory subsystems. Moreover, it is clear that non-declarative memory influences experience and behavior (the most frequently cited example is knowing how to ride a bicycle or play the piano, without necessarily being able to describe the movements involved).

A therapy séance can be seen as a series of present moments driven by the desire that a new way of being together is likely to emerge. These new experiences will enter into consciousness, sometimes as implicit knowledge. Most of the growing therapeutic change appears to be done in this way, slowly, gradually and silently. More spectacular is the emergence of ‘urgent moments’ that produce ‘moments of encounter’.”

Jean-Luc Nancy :

How can one, as an artist, give shape…? You are asking me to enter into the artist’s skin… That is precisely what I cannot do… And if I say » into the skin » it is of course very literally. The skin (peau) – “expeausition” (…) – is nothing more than the limit where a body takes its shape. If I think of the soul as “the shape of a living body” for Aristotle, I can say that the skin is the soul, or better, that it animates the body: it doesn’t wrap the body like a bag, it doesn’t hold it like a corset, it turns it towards the world (and as well towards itself, which thus becomes both a “self” and a part of the non-self, from the outside). The skin does not cover, it forms, shapes, exposes and animates this incredibly complex, entangled, labyrinthine ensemble, which constitutes all the organs, muscles, arteries, nerves, bones, liquors, which is in the end such an “ensemble”, such a machinery only to get in form in, through and as skin, with its few variations or supplements, mucous membranes, nails, hairs, and this notable variation which is the cornea of the eye, with also its openings – nine in number –which are not “inputs” or “outputs”, much less cracks or fissures, but instead the way the skin flares out or invaginates, shrinks and unfurls or expresses itself in various ways with the outside – food, air, odor, flavor, sound (we can add electrical, magnetic, chemical phenomena that mingle with what the “senses” tell us), – and the skin not only spreads from one opening to another but, I repeat, unfolds at each opening to form tubules, cavities, through the walls of which occur all the metabolisms, all the osmosis, dissolutions, impregnations, transmissions, contagions, diffusions, propagations, irrigations and influences (also like influenza). This system, which is both organic and aleatory, functional and hazardous (by itself essentially exposed), does nothing else but constantly reform, renew and transform the skin.

(Jean-Luc Nancy et Jérôme Lèbre, Signeaux Sensibles, Montrouge : Bayard Édition, p. 64-66)

Jean-Charles François :

For the apeaustle, the skin (peau) – expeausition – as the limit where the body takes its form, skin, edge where the pores are the form of the soul and animates the body, Saint-Bio of the contiguity of other bodies to the stars.

The peau-lisière (skin-edge) of Apollinaire, peauet until his trepanation, and peau-aesthete a-linear, was not at all police-wear, nor very polished, but poly-swarming, poly-swirling.

The emptiness of the soul is the form taken by this communion between the sensitive body and the epeaunym (in the sensitive lion eye of the Gaul primate).

Tim Ingold :

Wherever they go and whatever they do, men draw lines: walking, writing, drawing or weaving are activities in which lines are omnipresent, as is the use of voice, hands or feet. In Lines, A Brief History , the English anthropologist Tim Ingold lays the foundations of what could be a “comparative anthropology of the line” – and, beyond that, a true anthropology of graphic design. Supported by numerous case studies (from the sung trails of the Australian Aborigines to the Roman roads, from Chinese calligraphy to the printed alphabet, from Native American fabrics to contemporary architecture), the book analyzes the production and existence of lines in daily human activity. Tim Ingold divides these lines into two genres – traces and threads – before showing that both can merge or transform into surfaces and patterns. According to him, the West has gradually changed the course of the line, gradually losing its connection to gesture and trace, and finally moving towards the ideal of modernity: the straight line. This book is addressed as much to those who draw lines while working (typographers, architects, musicians, cartographers) as to calligraphers and walkers – they never stop drawing lines because wherever you go, you can always go further.

((Introductory text (in French ) to Tim Ingold,Une brève histoire des lignes, traduit de l’anglais par Sophie Renaut, Bruxelles : Zones sensibles, 2013. English original text: Lines. A Brief History, London-New York, Routledge, 2007.)

http://www.zones-sensibles.org/livres/tim-ingold-une-breve-histoire-des-lignes/

Gustave Flaubert :

An edge of moss bordered a hollow path, shaded by ash trees, whose light tops trembled.

Tim Ingold :

But what happens when people or things cling to one another? There is an entwining of lines. They must bind in some such way that the tension that would tear them apart actually holds them fast. Nothing can hold on unless it puts out a line, and unless that line can tangle with others.

(op. cit., p. 3)

Aleks Dupraz :

My relationship to research became more pronounced after a year spent relatively on the fringes of the academic institutions. While I was wondering about research that I could join or set up with a perspective of contributing to the development of action-research, my trajectory has been strongly affected by my participation in different spaces of research and experimentation that were for me the network of Fabriques de sociologie (I joined in 2015), the creation of Animacoop collective in Grenoble (initiated in Grenoble a few months later), and the seminar of Arts de l’attention in Grenoble (inaugurated in Grenoble in September of the same year). Thus, it is above all in the encounter that my research recommitted itself, getting summoned to where it sometimes seemed to be lacking. Indeed, despite my attempts to introduce myself otherwise, I was often identified in these circles as a student and/or young researcher at the University. This was particularly the case at 11 rue Voltaire, the first location of the Chimère citoyenne, when I was part of the research seminar of the Arts de l’attention. I then became aware once again of the extent to which being identified as an academic came at first to freeze something of an identity to which I refused to be reduced while at the same time assuming a part of the social and political function that this entailed and the responsibility that this seemed to me to imply. In this tension, I could not help but notice my attachment to the world of the University – for which I remain very critical – this in a political context in which the discourses arguing the waste of time or the luxury of reflexivity and research in literature and the human and social sciences tended to multiply.

(« Faire université hors-les-murs, une politique du dé-placement », Agencements N°1, mai 2018, Éditions du commun, p. 13)

Nicolas Sidoroff :

Let’s take an artistic example: music and dance. Considering them as practices strongly marked by the historical setting of discipline, they are clearly separated. You are a musician, you are a dancer; you teach (you go to) a music or dance class. There are cases, boxes or tubes on both sides. Crossbreeding is possible, but it’s rare and difficult, and when it does take place, it’s in an exclusive way: you’re here or there, on one side or the other, each time you have to cross a border.

Considering music and dance as daily human practices, they are extremely intertwined: to make music is to have a body in movement; to dance is to produce sounds. Since 2016, an action-research was conducted between PaaLabRes and Ramdam, an art center. It involved people who are rather musicians (us, members of PaaLabRes), others rather dancers (members of the Maguy Marin company), a visual artist (Christian Lhopital), and regular guests in connection with the above networks. We’ve been experimenting with improvisation protocols on shared materials. In the realizations, each everyone makes sounds and movements in relation to the sounds and movements of others, each is both a musician and a dancer. For me, the status of the body (the gestures including those for making music, the care, the sensations, and the fatigue) are very different than the one I have in a rehearsal or a concert of a music group. They are even richer and more intense. With the vocabulary used in the previous paragraphs, in these realizations I am in a form of “tâ/ache blanche” (white task/stain) dance-music edge or fringe. A first assessment that we are in the process of drawing up shows that going beyond our disciplinary boxes (exploding the border, making the edge exist) is difficult.

(« Explorer les lisières d’activité, vers une microsociologie des pratiques (musicales) », Agencements N°2, décembre 2018, Édition du commun, p. 265)