Retour au texte original en français : Demain, Demain !

Tomorrow, Tomorrow!

Ecolo-musical Lecture

For reflecting, dreaming, acting

Marie Jorio, 2018

Summary:

From music to ecology, from ecology to music

Examples of audio files

Extracts of texts of the programme

How did I become an ecologist?

From music to ecology, from ecology to music,

to break down the walls of denial, fear, anger…

Marie Jorio is an urban planner committed to ecological transition and has extensive experience on stage in theatre/music performances. She found herself in the situation of (trying to) break down walls, literally and figuratively, as early as her engineering studies, where her artistic sensibility had difficulty finding a place, and as an urban planner, as a weaver of physical and human links.

In the proposal “Demain, Demain !” [“Tomorrow, Tomorrow!”] she wants the audience to reflect, dream and act, in order to overcome the denial or stupefaction that suffocates us today in the face of the magnitude of environmental issues.

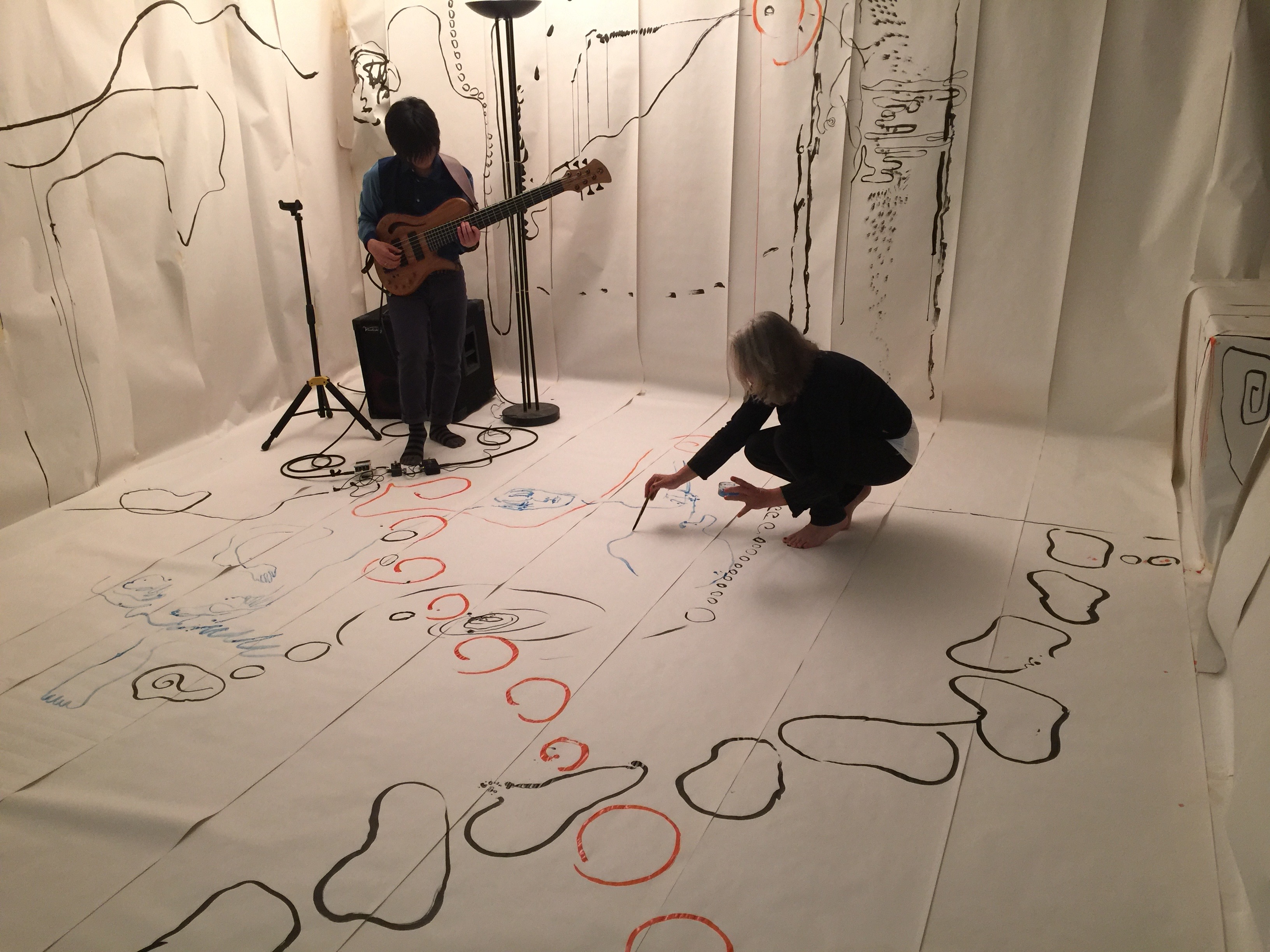

Accompanied by the theorbist Romain Falik, and by other guest artists depending on the venues, she puts in place an original form of sensitization that mixes the reading of reference texts by major authors on ecology with literary and poetic texts, and a sensitive musical accompaniment of Baroque and improvised music.

Considering that music, like all forms of art, is a form of demand and implementation of the happy sobriety to which our societies should turn, its crossbreeding with ecology becomes a foregone conclusion.

To make people want to read and learn more about ecology is another aim of the lecture-performance. The performance program, which is the result of a long and ongoing bibliographical quest, presents classics of the genre, such as rarer texts, fictions, essays or poems, and attempts to combine the bitterness caused by the observation on the state of the planet, an existential reflection and an enthusiasm for action. The reading can be extended by an exchange on the subject of books and reading suggestions.

Audios (other examples are available)

nelevezpaslespieds.blogspot/DemainDemain!

Extracts of text in the performance program

Pierre de Ronsard, Contre les bûcherons de la forêt de Gastine

« Forêt, haute maison des oiseaux bocagers,

Plus le Cerf solitaire et les chevreuils légers

Ne paitront sous ton ombre, et ta verte crinière

Plus du Soleil d’Esté ne rompra la lumière.

Plus l’amoureux Pasteur sur un tronc adossé,

Enflant son flageolet à quatre trous percé,

Son mâtin à ses pieds, à son flanc la houlette,

Ne dira plus l’ardeur de sa belle Janette :

Tout deviendra muet : Echo sera sans voix :

Tu deviendras campagne, et en lieu de tes bois,

Dont l’ombrage incertain lentement se remue,

Tu sentiras le soc, le coutre et la charrue :

Tu perdras ton silence, et haletant d’effroi

Ni Satyres ni Pans ne viendront plus chez toi. »

,

Reproduction (Poem by Marie Jorio, from the blog « ne levez pas les pieds »)

La ville semble proche de l’effondrement,

Ses habitants fourrés dans des boîtes métalliques,

Comme des petits pains frôlant l’indigestion ;

Le moindre grain de sel fait gripper la machine.

Tout cela est complètement fou

(et pourtant ils pondent).

Mais quoi ! La ville est-elle folle au point

Que l’on construise toujours plus

Sur des lignes pourtant saturées ?

Et 100 000, 200 000, 300 000 mètres carré,

Pour se faire élire, s’ériger une gloire, une fortune.

Les conducteurs de métro sont-ils condamnés

A rouler au pas dans la peur d’arracher un bras ?

The city seems to be on the verge of collapse,

Its inhabitants jam-packed in metal boxes,

Like bread rolls verging on indigestion;

The slightest grain of salt causes the machine to stall.

All this is completely insane

(and yet they hatch).

What the hell! Is the city so insane

That we build more and more

On lines that are already saturated?

And 100,000, 200,000, 300,000 square meters,

In order to be elected, to build a fame, a fortune.

Are subway drivers condemned

To riding at a slow pace in fear of tearing off an arm?

How did I become an ecologist?

Marie Jorio, August 2018

How did I become an ecologist? Why did I become an ecologist? It is interesting to ask this question.

First answer, very clear in my memory: Christmas 2002, I’m staying with friends in Lyon, their apartment in Croix-Rousse neighborhood. They subscribe to Télérama and I read an article by Jean-Marc Jancovici about global warming. My Cartesian and naturally worried mind is struck by the subject. I would spend the following weeks devouring his website; his somewhat haughty polytechnic tone is not enough to spoil its real popularizing qualities, especially when it illustrates the gigantic amounts of energy we waste, with conversions into a number of slaves. I realize irrevocably that our growth-based lifestyle cannot continue for long in a world of finite resources. This simple reading definitely changes the way I look at the world. I’m a beginner urban planner, working on the redevelopment of Les Halles, Paris’ central metro station; this work is somewhat consistent with my brand new environmental concerns, since it involves improving the capital’s public transportation network.

If I go back further in my memory, I find older traces of awareness of the fragility and infinite beauty of nature. A summer trip in the family car, probably on the “sun” highway south. We come across a quarry in operation; “Dad, what are we going to do when there won’t be any more stones?” I don’t remember much of the answer, which was supposed to reassure me that we would always find some. Always…. Until when? And then I discover and devour all of Pagnol’s books and take advantage of the summer vacations in a large property in Provence to spend whole afternoons in the garrigue. I observe the fauna and flora, invent paths and stories. My childhood and early adolescence are marked by immersions in the forest and nature, which the urban planner that I will become will completely forget to the point of being afraid of the slightest thorn and the slightest noise each time I return to nature.

How to deal with this sensitivity and restless consciousness? For 15 years, it has been more of a weight than anything else, a black cloud over my head that I had to forget as best I could in my daily actions. I savor the long summer evenings thinking that these may be the last ones… Practicing self-mockery so as not to get too much attention, I try to convince and make my colleagues and those around me aware of the climate issue and the depletion of resources. At the beginning of the 2000s, the subject is minor and controversial. The qualities of logic and rigor that led me to study engineering, without any vocation, are the same qualities that made me recognize in the curves and figures, brilliantly exposed by Jancovici, among others, an irrefutable fact. These same engineering studies have had the result of making me skeptical about the validity of scientific models to describe the living, or in any case to grasp their limits. Understanding that models are by definition approximate with respect to the infinite complexity of nature, was undoubtedly the demonstration of an ecological intuition that was unknown at the time. In any case, this ecological consciousness, if it does not translate into political commitments – I have seen up close the Greens of the Parisian microcosm who have perfectly cooled the idea I might have had of getting involved – has a very concrete consequence on my private life: while my engineer friends already have 2 or even 3 children, I take refuge in the idea of not having any, overwhelmed by the responsibility of leaving them a dilapidated world and a disillusioned tomorrow. However, I have enough social sense not to worry my friends that having a third child seems irresponsible to me in view of the state of the planet.

And then the environmental issue progresses in the media, as all environmental signals turn red. It is becoming difficult to ignore the issue. My job as a developer, building infrastructures and selling land to developers or social sponsors, is becoming a heavy burden. Of course, I have chosen to work on projects that are exemplary from an ecological point of view. But the worse environmental news accumulates, the more I am convinced that the scope of the changes to be made is enormous, and that continuing “business as usual”, mixed with green cosmetics, is totally trivial.

Changing is slow and painful. An immense anger overwhelms me. What can I do about it? What drops of water to bring into the ocean? If the legend of the hummingbird, which carries its share of water to extinguish the fire, puts balm in our astonished hearts, it nevertheless masks the need for changes that go far beyond individual initiatives. How can we live with this acute lucidity of the impending collapse? With the bad conscience of being better off than many others? How can we continue to breathe, to laugh, and find the path of action that will give meaning to this life that has become precarious? How can we live when we are aware that the human species has its days numbered? What killjoys these eco-freaks!

This anger, combined with a few accidents along the way, pushes me to change my professional path, to turn to teaching and counseling; to try to transmit new, possibly radical, ideas, while maintaining a certain independence of mind. And above all to slow down the pace, to sing, to get closer to nature, to better apprehend the necessary changes, and to calm down, little by little, the anger.

There are no answers, just paths to take. The practice of singing and performing arts are my lifebuoys of lightness and beauty to support the cloud which is much darker than fifteen years ago. And then sharing this weight with other convinced people, with whom there is no need to “show green paw”, is absolutely necessary for me to move forward. Consciousness is progressing, and we will soon all be schizophrenic: we know that we have to change everything, but we are only human, and we continue to live, to change cars, to discover Thailand… Some of us are hoping for a violent shock (but not too much) as soon as possible, which will serve as an electroshock. One thing is sure, being a shrink is a way to the future. And being an ecologist is not only an external struggle, more and more violent, but also an internal one, to try to stay straight in the storm of uncertainties and worries.