Encounter with Sharon Eskenazi

Jean-Charles François, Gilles Laval and Nicolas Sidoroff

November 9, 2019

Sharon Eskenazi taught dance and improvisation in several art schools and conservatories in Israël from 2000 to 2011. She graduated from the “Movement notation Department of the Rubin Academy of Music and Dance” in Jerusalem, and studied at the Université Lumière in Lyon where she obtained a Dance Master (2013). Co-founder of the group DSF / Danser Sans Frontières in Rillieux-la-Pape, she directed at the Centre Chorégraphique National in Rillieux-la-Pape (CCNR) in 2015 the projet Passerelles. She is the choreograph assistant of Yuval Pick since 2014. She is Artistic Coordinator and Assistant Choreograph at the CCNR.

https://dansersansfrontieres.org/les-spectacles-les-projets/

http://ccnr.fr/p/fr/sharon-eskenazi-coordinatrice-artistique-et-assistante-choregraphique

Summary :

1. General Presentation of the « Danser Sans Fronières » (DSF) and « Passerelles » Projects

2. « Danser Sans Frontières »

3. « Passerelles »

4. Relationships Dance/Music and the Question of Creativity

1. General Presentation of the « Danser Sans Fronières » (DSF)

and « Passerelles » Projects

Perhaps, to begin with, could you just describe a little about your background before the projects that took place in Rillieux-la-Pape for example?

So, I was born and raised in Israel. I lived there until 2011, when we decided to come to France – my husband is French, so for him it was like coming back – for me it was a real life change. And so my career as a dancer took place mainly in Israel, but I would prefer to say that I am a dance teacher and a choreography teacher. That’s my specialty: teaching choreography or creative processes, that’s what I did in Israel. In my work I’ve carried out a lot of projects between Israelis and Palestinians. I have a very close friend, Rabeah Morkus[*], who is also a Palestinian colleague.

Were you students together?

At one point, we were both in the equivalent of a “Conservatoire Supérieur” in quotation marks – in Israel it’s not organized in the same way. It is a group of young people who dance with the Kibbutz Dance Company. (It’s the second largest company in Israel, along with Betcheva.) That’s where we met. I grew up there and she joined us when she was 18 I think. I was about 18 years old too. It wasn’t on my Kibbutz, it was right next door. And so we spent a year together in this training program.

You say your job is to teach choreography, but is there a diploma? Did you go to school for this?

Yes, but that was later. I started… I had danced all my life, there, in their school, and then I did the two-year training course before becoming a professional dancer, and then I stopped. I told myself that I didn’t actually want to be a dancer and I wanted to stop everything. But I thought, still, I loved dancing, so I decided to continue. And I went to do a four-year Degree in Choreography at a dance and music university in Jerusalem, really similar to the CNSMD [higher education conservatory]. The three majors were: choreography, improvisation and notation. The notation system cannot be the same as in music, it tries to analyze movement through signs. So each notation has a different system to perceive space, time, body and body parts. It’s very interesting, I loved it.

So these are scores?

Yes, it’s completely another world, but it really opened up my thinking on choreography and composition. I learned a lot, and much more than choreography, because choreography includes scenography and performance, but also composition, that is to say how you create the actual score of the movements. That’s it, and after that I continued to dance, but in different projects here and there, and soon I started to teach choreography .

And the degree was for you to become a choreographer? Wasn’t it also to become a choreography teacher? You talked about the three majors, wasn’t there a « minor » in pedagogy or teaching?

I can’t say, because some people came out of this program and are now choreographers or dancers. I came out and I was a teacher, so it wasn’t turned towards it, but you had to take courses on – how do you say it? – teaching subjects or pedagogy.

Let’s come back to the projects between Israelis and Palestinians?

With Rabeah over the years, we have set up projects that use dance as a tool to bring the two peoples in conflict closer together. To be more precise: we have never worked with Palestinians who live in Palestine, so we are talking about Palestinians who live in Israel. When I arrived in France, we had just launched another project in Israel, and I was very disappointed: it was a bit of a shame not to be able to continue working with her. And then when I arrived in France, I said to myself that in fact it’s not only in Israel that there are problems of identity, of living together: how do you meet others? Without being afraid, how do you reach out to someone who is very different and who is sometimes in real conflict – well, this is perhaps less the case in France, but… When I arrived, I realized that there was a real problem of identity here. And so I had the idea of opening a place of creation for young people who love dance and who come from different social backgrounds, to bring together young people from the new town of Rillieux-la-Pape [suburb of Lyon], where we lived, it was just a coincidence…

How did you happen to get here? You talk about “coincidence”, about luck?

In fact, we arrived in the Lyon area by chance, because we were looking for a bilingual school for our children who didn’t speak French. And we found a school in Lyon, that’s why we moved there. And in Rillieux-la-Pape because we were looking for a house or an apartment, and we were not accepted anywhere because we didn’t have the necessary papers… You know how it is here, it’s very, very strict. And so “here” [in Rullieux-la-Pape], by chance, was the only person who accepted our file. So we said yes right away. And I didn’t work, I had nothing here; at first I decided not to look for work because the children had to face a very big change. And then, after a year, I decided to do a Master 2 at Lyon II in dance, more precisely in performing arts, because I didn’t really speak French and I had very little experience of reading and writing in French. I thought that if I wanted to work here, I would have to improve my level of French and also have a diploma or training in France. And during this Master, I decided to create the association “Danser sans frontières” (DSF) [Dance without borders] to bring together a group of young amateur dancers, who come from very different places and cultures, and practice different styles of dance.

Precisely, yourself, what style of dance do you come from?

I come from contemporary dance. But as I am more involved in the creative process, it is not a particular style of dance that interests me, but rather what is behind it, the content that people bring into their dance. So it can be urban dance as much as classical dance or contemporary dance. That’s what interested me in this project, to open up a place for creation. For me, creation is a very important act that liberates the person, that gives them access to something inside, to their identity; because to create, you have to know who you are and what you want. And so, for me, the approach was not to envision a dance group working with a teacher who would teach this or that dance or this or that choreography. In addition to the act of creation as a founding act, it was also about collective creativity because, if you create something together, you always have to build something in common, to have the possibility to talk, to share and so on. Those were our two goals and so I founded the association at the end of 2013. The group was created in April 2014 with 12 young people. From the beginning there was equality between girls and boys, really 6 and 6, so it was already good… And there were young people from Rillieux-la-Pape, from the new town as well as from other districts, and also from Caluire-et-Cuire. And we started to work on the first creation together, really the very beginning. So I suggested a few procedures, a few guidelines for creation, and each one created small things for the group, which we put together. Little by little, over the years, it really developed. And since the main goal was to give them the opportunity to create, at the end of the second year, I think, they created their own pieces. So, one person, a dancer, carried and signed the creation. And since then, it’s like that, they are the ones who create and I am there to do my job: to be an outside eye and to accompany them in their approaches, right from the start.

It took place in the National Choreographic Center of Rillieux?

Not then. It was a personal initiative and so I created an association which carries out its actions in Rillieux-la-Pape. So every year the town council gives me a time slot in a studio belonging to the town, and we work there every Sunday from 4 to 7 pm. So it’s a real commitment on the part of the young people, because it’s no small thing to be present every Sunday from 4 to 7 pm. And in fact it was a very clear axis: there are no auditions, it is not by virtue of ability that someone can be accepted, but by virtue of commitment. Being committed is also an aspect that I find super important for young people. If you decide to do something, it’s to see it through to the end. And it’s not “I’m coming, I’m not coming, it’s cool, it’s not cool.”

Did you sometimes have trouble with that?

Ah, yes! All the time.

And what do you tell people?

That means yes, sometimes I tell people for example that they can’t be on stage during the performance because they haven’t been present at rehearsals before. Because they might say: “Well, I can’t, no, I’ve got something else on, ah no, but actually, Sharon, I’m sorry, I’ve got a family dinner…” Then it might happen, but now, for example, I don’t have to worry about it anymore. And for the young people who work with us, as well as new people who join us, it’s so much a matter of course that I have practically no worries about commitment.

To come back to Jean-Charles’ question, you went to the Town hall to ask them to lend you a dance studio. And then, little by little, it got closer to the Centre Chorégraphique, later on?

Then, the partnership with the Centre Chorégraphique National [in Rillieux] began around the project “Passerelles”. In fact, from the beginning, in addition to all the initiatives that I mentioned earlier about collective creation, I immediately had in my mind the desire to undertake the “Passerelles” project. As I worked in Israel with a group of Israelis and Palestinians, a mixed group, I thought that it could be very interesting to bring the two groups together so that each group could see what it means to meet the other. What does it mean to look at another conflict a little bit from a distance, a different conflict, while not using the word “conflict”, but a social and cultural and political situation, such as the situation in Israel or the situation in France. What does it also mean to have very different identities? How everyone lives their own identity without hiding it, for example. What I found very present here is that… – perhaps there is a political desire or a cultural question? – but one tends to hide one’s singularity or one’s roots in order to be like everyone else. And so I really wanted the young people – I don’t know – blacks or Arabs who live here in the new city to feel proud of their roots, their origins, and to express them freely. And that it’s good to be all different and that everyone brings their own culture. So I thought that by organizing a meeting between the French and the Israeli-Palestinian groups, it would open doors for all the participants. But, at the beginning it was just a project without any money, without knowing if I would have someone behind me to carry it. And I was just starting to work with Yuval Pick[*], director of the Centre Choréographique National, at the time I wasn’t yet his assistant, I hadn’t even started to work at the CCNR. I explained this project to him, he was interested. It was a year and a half after my arrival in France and I no longer had a group in Israel, so I also had to help my Palestinian friend Rabeah to build one…

This was very laborious. At first I started the whole thing here on my own. The Grand Projet de Ville in Rillieux-la-Pape helped me to set up a “city policy” project, so I was able to get public money. And so it was absolutely necessary for this project to succeed. So we created a group together in Israel, me a little bit far away, but Rabeah up close. And all this was realized in February 2015, when the Israeli-Palestinian group arrived in Rillieux-la-Pape. The Centre Choréographique National provided the framework: that meant the use of the studio and also – because there was also the first floor – a place to eat and welcome everyone. There were 24 people in the Israeli-Palestinian group and 12 in ours, so it was a huge group. In addition, the CCNR granted dancer Yuval Pick time to lead the workshop, because the idea was to meet around dance, but not just in a cafe or to visit Lyon. We lived a week of real dance workshop together, with both groups. And it was really a human encounter and a very strong cultural shock for everyone. We had the feeling that “breaking down the walls” is possible. But it’s not that simple, because there were no walls already established between the two groups, because they were very distant, they were very different, culturally very distant. They had no language in common, as the French barely spoke English, the Israelis and Palestinians did not speak French. There was also no common history between the two groups and within each group taken separately. That is, within the Israeli-Palestinian group, there were Palestinians and Israelis who were not used to working together or doing things together. And within the DSF group here, as I told you, there were very different people. And it really had a “whhhfff” effect of – how can I put it? – yes, of coming together, actually of getting closer. People who were complete strangers at first became best friends a week later. It was also true for us adults who were around, we were very impressed with this power that dance has. I say dance, because it’s not just the fact of meeting each other, for me, it’s the dance that made it possible to meet the other, in the first place without using spoken language. That is, without words, and through the body, because the body speaks and it has this capacity to welcome the body of the other, probably better than through words. For them and for us too, it was a very powerful experience.

Let’s just explain a little bit the approach to this project and see how it was built. I started with the Town Hall and the “Grand Projet de Ville” to obtain public subsidies. It wasn’t a huge sum, 3000 or 3500€ I think, and I set up the project with that. In order to be able to cover the costs, I called on families in Rillieux-la-Pape to host the young people. The desire was to get the inhabitants of Rillieux to participate in this project, to really involve them in a common action. It went really well, because they were really there and they came to see the performance. These people, afterwards, kept in touch with the young people of the Israeli-Palestinian group and the French group. It became a circle close to the DSF group. In addition, these families made it possible to welcome the young people without having to take out the budget that this required. And then I also called on the inhabitants of Rillieux-la-Pape to volunteer in the kitchen: there were 35 young people and then the adults around. So there were 50 of us in all who had to eat every day, three meals a day, for young people. And as I had a very small budget, I needed someone who could cook, especially pasta, for 50 people. It was another way to include the inhabitants in this project. And the MJC [Maison de Jeunes et de la Culture – Youth Cultural Center] was also a partner.

2. “Danser Sans Frontières”

Do you remember how you contacted these people, these volunteers? Was it in the municipal newspaper?

Good question. There’s one very important aspect: at the beginning, I didn’t create the DSF group alone. I created it with Hatem Chraiti[*]. He is a hip-hop dancer-choreographer and lives in Rillieux-la-Pape. He is everything I am not: a man, a Muslim, who dances hip-hop. Whereas I am Israeli, woman, Jewish and I come from contemporary dance. I said to myself, voilà, it’s not enough to tell others to break down the walls, you have to start doing it yourself. So he started this project with me, and it was very interesting. Even when I did projects in Israel with Palestinians and Israelis, it was always in the field of contemporary dance. So this was different. I met him, and that was the first time I attended a hip-hop dance class – because in Israel it’s not like here, it’s not very common; although now it may have become so, but 10 years ago I don’t think it was. I worked mostly in places that train young people who wanted to be professionals, urban dance was not taught there. And so I was quite far from this culture and it was through Hatem that I was able to discover hip-hop. It was a way to work with some different people. We started the first “Passerelles” project together. He wasn’t born here, but he has been living and working in Rillieux-la-Pape for years, he has family and friends. So he also helped me to find volunteers, and at that time he also worked at the MJC [Youth Cultural Center] in Rillieux-la-Pape. Through Hatem we also made partnerships with the MJC, with the CCND and through DSF with the Town. So it was the three partners who finally brought the project to fruition.

Maybe we can go back a little bit. You talked about commitment, I wanted to know exactly what that meant: was it just a commitment of time? Or to be there? Or were there other things that came into play?

For me it was being there.

Is it a physical and active presence?

Yes, exactly.

Is it the only requirement?

Yes, that’s all that’s important actually. Because each person brings something, so if they are there, present, they will contribute. And if they’re not there (or only from time to time) it won’t work, neither for the group nor for the specific person.

So what was the profile of the people who were removed?

In fact I didn’t take anyone out. What was important for me was to demand a regular presence, because commitment is precisely one of the problems of young people living in the new town. Either they have fewer examples in their lives of real commitment, or they don’t feel responsible for what they do. So getting everyone to learn how important commitment is was an essential educational process for me. Because if people aren’t there, they’re not going to learn. It wasn’t so much a question of eliminating anyone, as of saying that success starts with this commitment aspect in one’s professional life. It was to make that clear.

So, I understand and even adhere to this idea, but at the same time what interests me is to know a little bit about the reasons for those who didn’t stay hooked.

So, here’s an example of a young person who had a lot of personal problems, as well as at school. He got to ninth or tenth grade and then he left school. And so he had a real problem with commitment, a difficulty in believing in something. I accompanied him for three years, from 2014 to 2017. Well I can tell you that I tried everything. I even went with him to the Second Chance School after he was expelled from his high school. So he spent a year at home doing nothing, and I tried with his mother and grandmother to make him continue DSF in spite of all his problems and it was not easy. And in the end I even went to his school to be the accompanying responsible adult and it didn’t work out. He stayed maybe three months in that school, and then he left. And then I tried again to get him back into DSF, because I thought that DSF was a framework that could help him, but I did not succeed. Now he’s no longer in DSF. And it’s true that it wasn’t the fact that we put commitment as the number one rule that led to him no longer being part of DSF, because he had every chance. And the door was always open and he knew it. But it shows that having commitment problems is not just a question of personality. It is also a question of life experience, of… not a family problem, but of…

… environment?

Yes of environment: what is around you? What makes you unable to be yourself completely in a place for at least some time? Because you don’t believe in it; because nobody trusts you, so you change all the time, so you leave, you come back, you leave, you come back, it’s super complicated. And it’s true that, for example, I know that at the Town Hall, they adhere to the DSF project, but once an elected representative told me: “but why don’t you work with people who are on the street or who are in a very precarious situation?” Because it’s true that the people of DSF are not like that now. Even at the beginning, the young person I was talking about was one of the most vulnerable. The others are students, they are also young people who are very well supervised in their personal lives.

Yes, there are a lot of future engineers among these young dancers…

Yes, they do major degree studies. But it’s also true that I believe and I hope that being in this context, in DSF, brought a tremendous benefit to everyone. It has strengthened their confidence and their professional path. Now some of them became professional dancers, thanks to that as well. But not all, DSF remains open to amateurs, it is not a professional group.

And just to conclude with this initial group, what happened at the first session? Or the first few sessions? At the very beginning? What was the exact situation? What were the dynamics that enabled the development of the group?

In fact, in the beginning it was not easy to establish trust with them because of their habits. For example, there were young people who practiced contemporary dance, hip-hop and “dance-hall” which is a dance from the islands, an African dance. But those who practiced these three styles of dance, did it in a way – how can we describe it? – in a very stylish way, that is to say: I produce, I copy the teacher, I produce a style of dance, there is a specific vocabulary that I master more or less. There’s no creative approach to it, it’s just a production approach, that is, producing something and doing it well. And so, for me, with exercises that are more focused on creativity, it was much more difficult. The difficulty was for everyone to be able to develop something creative to get them out of their comfort zones: “Ah, I know how to turn on my head, I know how to do this or that well… whatever…” And through this approach, to be a little closer to artistic endeavors, because that’s what interests me, in the end, it’s art. And MTV’s video-clip isn’t art. Art is all about being able to touch someone’s sensibility. That’s what has been very difficult. If we talk about walls, that’s where the highest wall is. In this city anyway. To show what one is capable of doing specific to oneself is always dependent on the dominant culture of the group to which one belongs, or else, one risks being rejected. This is a phenomenon that can be observed everywhere. But it is even more true when one grows up in a city such as the new town of Rillieux. Then it is not two or three meetings that made the difference. This work took a few years. But at the same time, I knew that it was very important to make them discover the art of dance, because there are some who had never come to the Maison de la Danse for example, had never seen a dance art performance. Some had years of “cultural” practice behind them, and others didn’t at all. And so, just this encounter between people who practice culture or art differently, makes everyone grow. Moreover, the idea was to make them discover the art of dance in all its forms. So we went to the Maison de la Danse, which even organized for us a visit behind the scenes to discover the different professions. And after the Passerelles project, they were really “at home” in quotation marks, at the Centre Choréographique National. So they came to see almost every performance at the end of the CCNR residency, and this is really hard-core. These are emerging companies that are doing things that are not in the mainstream, not in the practices that are recognized by the institutions. How can I put it? That’s not what we see at the Maison de la Danse [laughs]. For example, even very simply the question of homosexuality: I remember one time, a company had worked around that, and for them, it was really the first time they’d seen such free expression around that subject. Then there’s the question of nudity (“you see what I see?”) [laughter]. So, it was also a way of making them discover something artistic or sensitive in them, and to see that it’s OK. We are allowed to touch things that are sometimes forbidden or hidden. So all this was part of breaking down the walls of the facade. Did I answer your question?

We can try to go into more detail. In PaaLabRes, we talk about the notion of protocol, the “trick” that allows it to begin. So Jean-Charles’ question was also about when they arrive, on the first Sunday at 4 pm. How do you open the door, what do you say, the question of the locker room and others? And then, what do you tell them at the beginning, how does it start, is it without words or with words, and what is the first activity you make them do?

In fact, if I remember correctly, it was 2014, but I think we started talking because this is not a dance school. We really started from scratch to build the group. So, one Saturday or Sunday, a group arrived… everyone introduced themselves, a little bit, and then I explained to them my intentions on creation, a little bit like I told you. I started by telling them about the “Passerelles” project, because it was already in my head, and I wanted them to know about it to see if they would be interested. We talked about the fact that everyone comes from a different technique or style of dance, that I didn’t intend to put those aside and just do contemporary dance. I wanted to make that clear, so that’s the first thing I put on the table: everyone can stick to what they’re doing, it’s all right, we can still do hip-hop if we want! It was very important, because they were a little bit afraid of losing their habits or what they know how to do. So I don’t remember if we did the meeting and danced right after, or if it was the next time? I think we started to dance right away, in this first meeting. I proposed exercises that allowed them to stay in what they knew how to do and still converse – dance – with the other. I immediately started with dancing. We talked, but there was immediately an action of movement and dance. I wanted them to understand the process, and to see that it wasn’t a dance class like they’re used to (with a teacher there, the dancers are behind and do what the teacher does). That’s not how it works at all. I’m there, I’m talking, I’m giving images, and they have to react, that’s it. Well, at first it’s difficult, because as I told you, they didn’t have access to this way of doing things. They only had access to produce words they already knew: sentences, words and vocabulary they had acquired.

What images do you give? Do some work better than others or not, some you are accustomed to using or not, and why?

With DSF, I try to give images the most – how shall I put it? – practical, very action-oriented. [She shows with gestures]. Because they were really amateurs who didn’t know each other, so there were a lot of barriers that made it not so easy.

Images are not things that are projected on a screen?

Then, “image” may not be the right word because, in fact, they are instructions for actions to be carried out. For example, it’s holding hands. And from there, we can suggest things, such as forbidding separation, to see what we can do with this idea. That’s the kind of situation that everyone can do, even if it’s never simple, because it touches on something intimate. It’s not a question of producing something like, “Hop! I’ve done a spin round and you say ‘wow!’” It is not in this context that it works, that it vibrates. So I try to do simple things, but not that simple. Because they are still dancers: they have to feel the presence of a challenge in relation to the dance, and at the same time it has to remain simple enough or clear enough in the actions so as not to put them in difficulty. I try to find that balance and then improvise a little bit with what you can observe. I prepare something, but then the group improvises on it. And I don’t remember exactly what I was doing, of course. [laughter]

It doesn’t matter…

But for sure it was in that order, because I always work like that and little by little, from encounter to encounter, it began to make sense. But it took a lot of time. And today, for example, if I invite choreographers to work with the DSF group, and even I from the outside, I say “wow”, it’s incredible how they dance, how available they are. It’s not only the readiness of their bodies in the dance, but it’s also the openness of their inner strength. That is to say, there are no limits and it is very impressive. And it is also because, after five years of working together and with me, a strong nucleus has been formed. They were able to meet choreographers, dancers, they participated in workshops, internships, with a lot of people, they saw performances and at the end they also worked with Yuval Pick, they were able to experience a real creative process with a choreographer. All this has made them super available and super open-minded.

There’s a trust that has also been established between them, which I felt a lot when I went to see the performance.

For them, it really became a family. A few days ago, on October 30 [2019], we presented a performance and they spent an evening together. In fact, they are together all the time outside of DSF, so they really became like a small family and very close friends… They go on vacation together, it goes beyond what happens in the studio. But it’s true that the trust between them helps them to be free, because it’s always the other’s look that scares us. Everything changes when the other’s gaze becomes so friendly…

3. “Passerelles”

We can go back to the “Passerelles” project. So, for example, if I understand correctly, it was to invite young people here – or not so young, I don’t know – from Israel and Palestine; so could you describe a little bit the make up of this group. For example, you said that the Palestinians live in Israel, but where in Israel, and the same thing for the Israelis?

Well, in the first group that came to Rillieux-la-Pape in February 2015, there were 24, 12 Israelis and 12 Palestinians (or very close to that maybe 11 and 13 or something like that). And it was very important for Rabeah and me that there were not 14 Israelis and 3 Palestinians because it happens very often. Because, for Palestinians, it’s not easy to do things with Israelis. Parity is sometimes not respected at all when doing things in Israel. And it was also very important for us that there was parity between men and women, so there were really almost the same number of boys and girls, of Israelis and Palestinians. Rabeah and I both come from northern Israel, near Lebanon, and we grew up in the same area, she in a Palestinian village, and I in an Israeli village. And so most of the Palestinian youth were from northern Israel. Just to perhaps explain: there are about a million Palestinians living in Israel.

They are called Arab-Israelis?

Yes. For me, first of all, they are not Arab-Israelis. This is the name that the Israelis have invented so as not to say that they are Palestinians and not to create this link with the Palestinians of Palestine. And if we ask the Arab-Israelis for their nationality, they will say that they are Palestinians.

Yes, I see.

As I knew that between the Israelis and the Palestinians, it was not easy, there was a real problem of affirmation of identity, especially among the Palestinians towards the Israelis, and of consideration of the Israelis towards the Palestinians. And so, in the “Passerelles” project, there was a moment when France 3 TV came to interview them in the studio here in Rillieux-la-Pape, there was a journalist and a photographer. So they filmed, but they said to me, “But we don’t understand, who’s who? We don’t see any distinctive signs.” And so I said, “Yes, well, it’s true,” and I decided to improvise and ask them to come to the camera and say their first name, last name, and where they came from in the language they preferred. And so all the Palestinians – and they all have Israeli nationality, they all live in Israel – all the Palestinians, all of them, came to the camera, they said in Arabic, “I’m so-and-so, I’m a Palestinian, ah! and I’m a Palestinian who lives in Saint Jean d’Acre in Palestine.” For the Israelis, even Saint Jean d’Acre is totally in Israel, not just for the Israelis but for everyone. For the Palestinians, it is in Palestine. And for the Israelis, it was a real shock that someone in the group who lives in Israel could say that she or he is living in Palestine. It’s quite extraordinary. And I knew that the Israelis were going to be extremely shocked. So, I mention this anecdote just to explain that Rabeah and I can say that we are neighbors. But in Israel it’s not like here, the communities don’t live together. That is to say that the schools, the National Education, are separated. So you can grow up five minutes apart and never meet a Palestinian with an Israeli, except when you go shopping. The systems are separate, so you grow up separately. And sometimes you don’t even speak the official language because, if your parents are not educated or they are not in contact with Israeli society, you can finish school and not being able to speak Hebrew for example.

But can you still live in Israel without speaking Hebrew?

Then it’ s not easy: you create second-class citizens who don’t have the same opportunities, because they don’t have the same ease of access to power or to people, or even to education. Because if you don’t speak Hebrew, you can’t go to university. So, for example, most of those who have money go to study abroad. They get around the problem of not speaking Hebrew. They don’t watch Israeli TV, which is in Hebrew. They watch TV from Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt. So, you live in Israel, but you don’t take part in Israeli culture at all.

What were the dance practices of these two groups?

Rabeah is a true pioneer in the Palestinian community. In addition to the problem with Israel, with the Israeli identity, etc., the Palestinians also have their internal problems: because there are Muslims and there are Christians. And there is also a war between Christians and Muslims, which is not easy. And besides, dancing is not at all approved of, neither in the Muslim community nor in the Christian community. It is difficult to accept the presence of artistic practices and that women could be allowed to dance. Well, today that has changed, I’m talking about twenty years ago, when Rabeah started, it was not accepted at all. Today, little by little, it is beginning to be so. She was really able to bring this to the heart of the village. She created and founded a dance school, which I believe was the first dance school to be established in the entire Palestinian community. She advocated this idea a lot, and now there are students who are grown up, and some of them even became professionals. But it’s a continuous struggle. The whole Palestinian group was made up of young people who gravitated around Rabeah, and therefore did not live far from Saint Jean d’Acre, the Palestinian village. As far as the Israelis were concerned, it was more complicated, because I was already here and there was no one to federate a group. And so, we found them somewhat like that, on the basis of those who were interested in this approach, in this project of working with the Palestinians. The idea was not only to come to France, but to create a group in Israel, and really offer something interesting through working together. In fact, this group was created precisely to go to France and a few months later, the group didn’t work anymore because people were too far away from each other. In fact, the group was created two months before the departure. That means that in December 2014, it was the first time they met. When they arrived in France, they hardly formed a group. For them it was the very beginning of the project, and there were 24 of them, which is too many people to manage a group. There has been a big change in the Israeli-Palestinian group that came for the second time in 2015: it is not the same group, but there is, like here, a core group that has followed the project from the beginning.

The first time they saw each other in Israel/Palestine is in December 2014, so did Rabeah use the same methods as you?

Yes, but in their group there was less difference in dance styles. Because she works a little bit like me, so those young people already were used to that. And the Israelis that we found through another friend who works with us, also already knew this way of doing things. However, for them, it was the fact of working together that was new. And Rabeah and I really insisted that all the meetings take place in the Palestinian village. Because often the strongest ones ask the weakest to come to them. It’s easier to meet in a Jewish town than to go to a Palestinian village. So we said: well, those who will be accepted into the project will be those who have the will to cross that wall, that door. That was almost the audition for the group: who dares to come several times to a Palestinian village without being afraid. That’s what they did… The young people of Rabeah invited the young Israelis. For example, they also spent a weekend together, being invited to stay with Palestinian families. Because it’s not just dance, not just art, it’s also a civic initiative. Being invited to their homes has been a real turning point for them. It was also always a very warm welcome, and so it was very important.

And what was the language used in the meeting in Israel?

It was Hebrew, because in spite of everything – I said that they were different educational systems – they learn Hebrew in school. Then there were some who didn’t speak Hebrew, for example, a young person who was in eleventh grade. But the others spoke well. The official language was Hebrew. Then we tried to use Arabic and Hebrew systematically, it was practically a political assertion. The ages were also quite different. There was a young man who was 16 years old, but also a 25-year-old girl who was already in a Master’s program in Israel. She spoke English, Hebrew and Arabic fluently. So there were all kinds of situations.

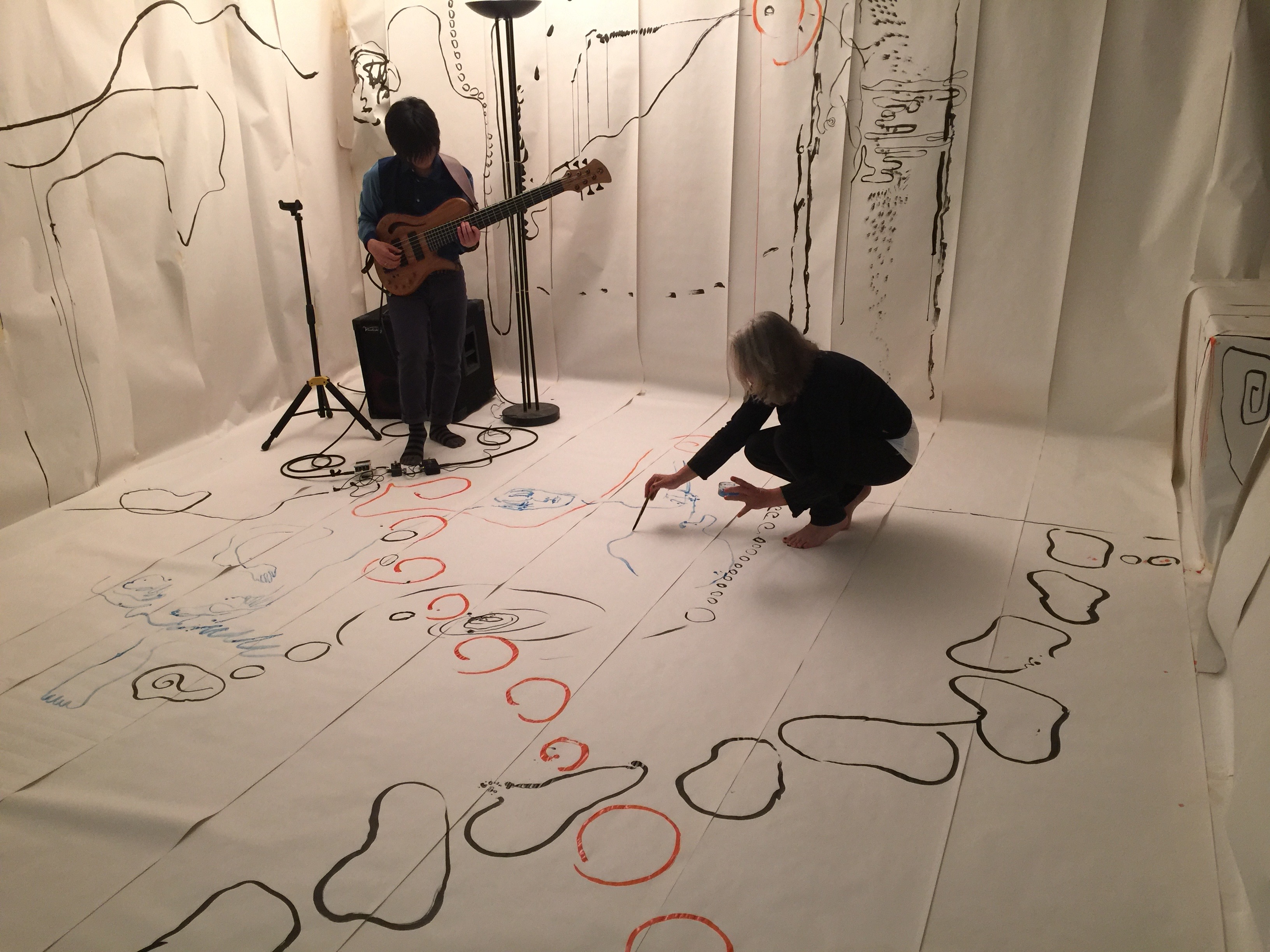

If we come back to Jean-Charles’ question, so in France, at the Centre Chorégraphique National, the two groups that came in, what did you make them do and how? Was it a workshop with Yuval Pick’s company?

Yes, and every day there was a dance class with Julie Charbonnier[*], a dancer from the company, morning and afternoon – not every day – and there were sessions with Yuval. There was one time when we did things between us precisely to develop the cohesion of the group. We also did a performance at the end of that week, with each group separately. During that week we prepared the performance a little bit, each group rehearsing what they were going to present. And then we worked with Yuval to prepare the performance – it wasn’t a real performance – in what looked like a master class open to everyone. During the performance, on Friday night, the DSF group presented a piece, the Israeli-Palestinian group presented a piece, and at the end Yuval organized a directed improvisation in front of the audience with everybody, 35 people on stage. And so we prepared that too. We visited Lyon, we had an evening at the MJC [Youth Cultural Center], we had an evening debate with the inhabitants of the city as well. What else did we do? [Laughs]

I was present at the debate, it was very important after all, especially between them.

Can we find out what happened in this debate?

In fact, in the debate, precisely what I told you about the moments when everyone said where they came from in their mother tongue and which raised this question: can the Israelis accept the fact that Palestinians feel Palestinian and not Israeli? And so there was all this difficulty between the Israelis and the Palestinians.

The debate was very intense.

Yes we can say that. So it brought out a lot of things between the Israelis and the Palestinians. It is much easier to express oneself freely outside the territory, and to talk about it, to exchange ideas. Because in Israel, it’s not always very easy. So, for them, it was really a very strong and revealing time. Because the Palestinians were also afraid that the Israelis could not accept this, but they found out that this may not have been the case. So, it was a powerful moment and in the debate this issue came out. Even if to some extent it’s a very intimate issue that doesn’t concern the French, it’s like in every peace agreement, there’s always someone else, there’s always a third person, because in a couple you need a third person to facilitate the exchange. The presence of the French group also served a little bit for that too. Afterwards it was a debate in three languages, so it wasn’t always easy. But what more can be said about this debate?

Did they talk about it among themselves afterwards?

There, there was then a debate, but it was an intimate, internal debate between us. And it was very, very, difficult, much more difficult than the first one. But I think that during the first week, they didn’t talk much among themselves, especially not about political problems. There was also a real language problem, because English was really very minimal among the French. So it wasn’t a very sophisticated debate. And they were twenty years old anyway, and in the Israeli-Palestinian group, half of the group was underage. The first time there wasn’t much verbal exchange between the young people. But on the other hand, the exchange in the dance was super powerful, we felt a lot of things, even without talking. And that’s what led us to say that, in fact, it was impossible to end there, it would have been a pity. We wanted to organize another meeting, this time in Israel…

The return match.

That’s it, the return match, exactly, and so we left ten months later for Israel, in December 2015. For that I had a “politique de la ville” grant, it was easier to convince the decision-makers of this necessity because they had already seen the “Passerelles” project number one. So we got a subsidy to pay for the plane tickets. It must also be said that the first rule I gave myself was that there should never, ever be a barrier through money, that someone could not do something because they didn’t have money. In fact, they contributed a little bit, because it’s important to say that not everything falls from the sky. But if someone couldn’t pay that amount, I would make sure that the full amount was provided. Some come from very, very modest families, so it’s important. So we went to Israel for a week, and it was a bit the same idea: to do workshops and encounters around dance. But this time, there was no place like the Centre Choréographique National that hosted us for the whole week. We went for two days here, one day there, like that, everywhere in Israel, to meet Israeli and Palestinian artists. Well, it was more Israeli in dance, because there is still not much dance among Palestinians, even if it is starting. But we met other artists and musicians, we made several encounters all over the place. For example, we did an activity in Haifa in a cultural center for the three religions and we also presented the first film “Passerelles ”. We went to Saint Jean d’Acre and we worked with an American dancer who danced for Alvin Ailey. She came voluntarily to give two full days of training. We also went to Tel Aviv to meet a choreographer, we had an improvised jam session with a musician and some dancers. We spent a day in a dance and ecology center: a dance center that defends the environment, for example where water is collected. The whole system is ecological, they built all the studios and the whole building, everything redone with earth and things like that, with a strong ecological commitment. And for example, they do work with people with disabilities. We also spent two days at Kfar Yassif, which is the village of Rabeah.And so we met and danced with an ethnic dance group, a Palestinian dance, the Dabkeh.

The Dabkeh ?

Dabkeh is the Palestinian dance, the traditional dance of Palestine, not only from Palestine but it is very much linked to the Palestinians. Now, because there is a real need for identity affirmation, many young people are starting to learn this dance as a symbol of their Palestinian identity. There was also a musician specialized in derbuka – what he did was magnificent – who played, and afterwards we danced with him, we improvised.

4. Relationships Dance/Music and the Question of Creativity

Precisely, this was a question: the relationship to music in all these projects. How does it work with the music, or the musicians?

Normally, for example, when we work in the studio, there is no musician. However we always work with music, it’s very important…

Is it recorded music?

Yes, it’s music that we like, that stimulates the desire to dance, that pulses [snapping her fingers].

Music that you like, that is?

It’s not the music we listen to at home, but the one we like to work with the dance, that is to say to make the body work, I don’t know how to explain it to you, I can make you listen. For example: Fluxion, Monolake, Aphex twin.

Then, do you choose the music?

Yes, if I give the class, I choose the music. I find that this music will make you want to do such and such an activity or such and such a type of movement, it creates this desire in the body. Then, everyone uses different music. And if we can work with a musician, it will really be a project built around that, because it’s very specific. If I work with music and pieces that I know and that I choose, there is an extraordinary diversity: I can choose at one time to work on Bach, because I want that kind of atmosphere, and after that, an electronic thing that gives a different energy, or a tribal or African or punk piece, and so on. This gives a much richer palette – rich is perhaps not the word – larger than a single musician who brings a specific color. But it’s super interesting; for example, when we worked with the Palestinian musician. But it was just an experience that we couldn’t develop further.

And the participants provided music as well?

No. But it’s a good idea. [laughs] I’ll remember it.

This idea of creativity is not completely obvious as far as I’m concerned, because it can be declined in millions of registers. Especially, I was wondering, for example, the question of the stage, because contemporary dance seems to me to be completely linked to this notion of “stage” in the sense of a theater and therefore to choreography. While other forms, notably hip-hop, have their origins…

In the streets…

Yes, and the street is a stage but it is not at all that particular theatre stage. And therefore it has totally different rules, especially in the idea of what we could identify as creativity. (Of course, I don’t know if what I’m saying has the slightest reality.) On the other hand, there is another problem: you said that not only the Palestinians didn’t practice dance, at the beginning of your friend’s project, but society itself didn’t see dance as something “good”. But at the same time afterwards, you say: ah but there is nevertheless a traditional form of dance that exists?

But it is not at all the same, for example the Dabkeh is danced originally only by men…

So there again, traditional forms of dance seem to me to be quite far from the notion of stage in contemporary dance… And it’s true that, also, we have seen a lot in recent years of recuperation, well, even for several centuries, it’s the tendency of the West to recuperate forms in order to stage them. So it would interest me to know how this is articulated within this project. Because there are also walls that need to be broken down, but the danger of breaking them down is that one form might eat the other.

Hm… It’s true that in street hip-hop, we can rather talk about « battle » nowadays, there is a lot of creativity.

That’s what causes the one to beat the other.

That’s it. And then in fact you improvise with everything you have, everything you are able to do. That’s it, so it creates beautiful moments, except that it’s not a creation, because it’s not writing, it’s improvisation and it’s the present moment. It’s not the same at all.

It’s not writing?

I mean, it’s not a choreography, sorry.

Isn’t it inscribed into a body that moves? Isn’t it learned, can’t it be reproduced?

It depends. For me, the creativity in hip-hop is really in the battles. Because there’s this notion of [snapping her fingers] to titillate the other one and always take it to a higher level of I don’t even know what, body, invention, etc. But there’s another aspect of battles, it’s that they’re very much about performance. That is to say that the most important thing is not to show something more intimate, more sensitive, but to show a performance and to make it “spotless”. So, for example, personally, I’m less interested in that. It’s not a question of style of dance, because this aspect doesn’t interest me at all in contemporary dance, where it also exists.

Yes.

It’s not a question of style of dance, but a question of approach. Then, it’s true that when you choose to highlight something more intimate and inward, you can’t do both. Because you said earlier that one is going to crush the other. I don’t know if I answered your question properly.

Yes.

So, for me, it’s not a question of recuperation. I know the problem of colonialism in art. But for me it’s not a question of style or aesthetics, it’s a question of what interests me in the person who dances. Afterwards, the first time I saw a “battle”, I saw this creativity, I thought “Wow! That’s really interesting”. But how can you keep this creativity outside of this competitive performance atmosphere? So that there would be this possibility of being in the more fragile, more intimate nuances. For me, it’s not a question of aesthetics, but that suddenly I might see in the person something very inventive, very innovative even. Even if this person doesn’t know what she or he is doing, it just came out like that, so it was amazing.

It’s a bit like that in all improvised forms, isn’t it?

Yes, but it depends on the objective of the improvisation, on each person’s experience. For example, in a “contact improvisation” jam or other forms of jam, the goal is not to impress the other person, and there’s not really an audience watching. It’s not a show in the form of a jam, it’s a shared experience.

Yes, I see.

Then, I don’t know, maybe there are other forms of improvisation with people who have other goals. Everything exists, and so… I think it is important that things have a purpose. For example, if the objective is to win something, it already means that we’re in competition; well, for me, that’s already problematic. Because we can’t compete, we’re different, so everyone brings something else. I understand the logic of competition, but for me, it’s not a context that can allow you to be really creative. Because you have to impress all the time, impress even more. So, it brings out amazing things, but the goal is not to bring out amazing things. I don’t know if I’ve answered your question, but for me, the goal is not to recuperate something but to lead to something else.

And in classical dance, you also have a competition…

Yes. That’s right. Classical dance today seems to be only interested in competitive high-performance.

Performance in the sports sense of the word.

Yes, if I do sixteen pirouettes, and then I manage to jump [snapping her fingers] and land well and be “perfect”, then the audience applauds. So, it’s like in a battle, where the body performance is much more important than “what does that mean.” Because why are we on stage? We’re not on stage to impress, I don’t know, maybe we are? That is to say that I’m not against virtuosity, but it has to serve a purpose. If it only serves itself, I’m not interested. It can be beautiful, but I’m not interested in it in artistic terms. It’s like the Chinese, they do things where you can only say “Wow!”, it’s beautiful, people are there and they turn on each other’s heads, some amazing things, but for me, it doesn’t move me at all, absolutely not at all. So, of course, I was the one who led the project, so you could say that it was my sensitivity that created a bit of a guideline. I think that, perhaps, when each project is directed, it has the color of the one who is at the head of it, it’s somehow natural. In any case, I think that even today, even after five years, we can completely see the presence of urban dance in everything they dance in DSF. So that hasn’t been erased, even though what they do is also contemporary dance. I think that even Jérôme Ossou’s last creation had a very urban aspect, with jackets and codes that match the daily movements, nurtured by what they experienced, for example the work with Yuval Pick.

I might have one last question. I have to choose it carefully [laughter] (it’s six o’clock). There was the idea in February 2015 of doing something at the Centre Choréographique National, with the Yuval Pick Company, etc. So, it’s a matter of bringing in outsiders, less the idea of “professionals” than the idea of an “exteriority” to the project itself. Then in the trip to Israel in December, you’re going to meet a lot of other people. Do you have a specific approach towards these people, who will be at the center of an activity, but very briefly within the overall project, around the idea of an encounter that shifts or surprises? At the place where I work, I’m fairly comfortable allowing very different musicians to meet each other. We build situations that allow them to start questioning the fact that it doesn’t work the way they think it works, that there are foregone conclusions that they need to deconstruct. That’s a big part of my job, and I like to do it. On the other hand, if at some point I’m told that Palestinians and Israelis come and meet each other, I have a whole literature of political struggles and history, but I have fewer tools at my disposal to develop situations. What do you expect from the invited guests? Do you make particular requests to the Yuval Pick company’s interveners on the first day, or not? Because I’m not sure there’s a need for it either… To sum up: how do you go about organizing the encounter of this project with outside contributors?

I did nothing special, except to present a little bit of the history of the group and its composition. I didn’t do anything else because, in dance, we dance. It can also be what you said, to organize a very specific encounter in order to find other ways to dance. But normally, if you have a very heterogeneous group of people, the fact of dancing together is going to create that right away. In other words, there is no other way. We work with “contact”, we don’t work frontal, we work without mirrors and we only work with each other. So, at the end of an hour and a half, well, it’s very rare that you don’t feel close to each other. That’s true! That is, it’s very physical, it’s not in the head, it’s not intellectual, it’s just that it’s a reality that happens between people who dance together and who have to touch… But it’s not a physical contact like we have in everyday life, it doesn’t lead to anything sexual or empathetic, it’s both neutral and functional, but it still creates a very intimate relationship, in a very different way than in the life as we know it. In fact, almost everyone who intervened – here with Yuval, his dancers, even in Israel – had a bit of the same approach. Not all of them, there are all kinds of approaches, because we also did a class and learned a choreography, but everything was lived through as a special experience. So, every time it happened, it was a new experience, and they were open to that. But most of the time it’s the process itself that creates that, regardless of the primary objective of the course. That is, I can do a course around a subject, but what will happen in an underground stream is what I think is important. So, we can organize very different workshops, but in the end, it will be what is going to be the most present in the overall feelings of the people. That’s my experience, I work with a lot of very different publics, so I can say that it almost always works. Then it might not work for a person who really feels in danger about that. Just, maybe to finish the story of “Passerelles”, it’s important to say that after these two projects, there was another project in Bordeaux. But the last project that we did together, with the two groups, the Israeli-Palestinian and the French, was a creation with Yuval Pick, the choreographer of the Centre Chorégraphique National. The piece is called “Flowers Crack Concrete”, with the idea of flowers cracking concrete: how can you make the walls between people break down? The whole piece was about that and the question of how can we be singular and do things together? Not to erase individuality in order to be together, but to live one’s individuality in order to create an ensemble. That was Yuval’s objective, and at the same time he created a piece himself for his dancers with the same idea, and one with this group. This time there were 12 Israeli-Palestinian and 12 French. It was presented at the Maison de la Danse and in Israel in 2018. This project was very important in terms of budgets and organization, this time it was carried by the CCNR, not by DSF.

Thank you very much.

Artists mentioned in this Encounter

* The dancer Julie Charbonnier started her professional training in 2010 at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP). Three years later, she moved to Bruxelles to join Génération XI of P.A.R.T.S, a school founded by the choreograph Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. Then in 2014, she joined the team of the CCNR directed by Yuval Pick, as permanent dancer. She starts this adventure with the duo Loom, which is a piece combining a great subtility and a powerful physical involvement. http://www.ccnr.fr/p/fr/julie-charbonnier

* Hatem Chraiti . hip-hop teacher and events organizer. At the time of the founding of « Danser Sans Frontières », he was a teacher at the MJC of Rillieux-la-Pape. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fU9uHfdmgk8

* Rabeah Morkus is a Palestinian dancer born in Kfar-Yassif in 1972. She studied choreography and dance pedagogy at the schools Kadem and Mateh Asher. She joined the Saint-Jean-d’Acre theatre and the Kibbutz Company directed at that time by Yehudit Arnon. She participated to several creations conducted at the alternatie theatre of Saint-Jean-d’Acre by Hamoutal Ben Zev, Monu Yosef and Dudi Mayan. In parallel to her activity as a dancer, Rabeah works at the rehabilitation through dance in a project with the goal of helping children in conflict with their family and the women who are victims of domestic violence. For her, dance is also a means to overcome traumas . http://laportabcn.com/en/author/rabeah-morkus

* Yuval Pick .Director of the Centre Chorégraphique National of Rillieux-la-Pape since August 2011, Yuval Pick is a very experienced perfomer and choreograph. He studied at the Bat-Dor Dance School in Tel Aviv, he joined the Batsheva Dance Company in 1991 until 1995 when he pursued an internaltional career with artists like Tero Saarinen, Carolyn Carlson or Russel Maliphant. He joined in 1999 the Ballet of Lyon National Opera and in 2002 he founded his own dance company, The Guests. He created pieces featuring an elaborated movement writing, and he collaborated extensively with musical composers, in ritual forms of dance,with an always questioned balance between individuals and the group. http://www.ccnr.fr/p/fr/directeur-yuval-pick