Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean-Geoffroy’s contribution is in two parts. On the one hand, a research article, “Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives”, originally published in English under the title “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”, by Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean Geoffroy, in the proceedings of the conference organized by PRISM-CNRS in Marseille (May 2022).

On the other hand, the transcript of a meeting between Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Jean Geoffroy, Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff in Lyon in February 2023.

Access to the two parts and their French versions

First part

Access to the article “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”

Access to the French translation “Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives”

Second part

Encounter with Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff

Access to the French original version of « Rencontre avec Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff »

Encounter with

Jean Geoffroy, Vincent-Raphaël Carinola

and

Jean-Charles François, Nicolas Sidoroff

1erFebruary 2023

Translation from French by

Jean-Charles François

(with the help of Deepl.com)

Summary :

1. Origin of the Collaboration

2.1 Toucher Theremin and Agencement

2.2 Toucher, Hands/Ears Correlation

2.3 Toucher, Notation

2.4 Toucher, Form

2.5 Toucher, Process for Appropriating the Piece

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, Smartphones, Primitive Rattle, Virtual Spaces

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, the Path to Virtuosity, Listening

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, a Collaboration Composer/Performer/Computer Music Programmer

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, the “Score”

3.5 To conclude: References to André Boucourechliev and John Cage

1. Origin of the Collaboration

Could you retrace the story of how you met, how did your collaboration come about, and what was its context?

We already worked with Christophe Lebreton[1] on different projects and although Jean and I had often crossed paths, and I knew and admired his work and his various collaborations with composers, I was looking forward to the opportunity to work with him. The point of departure was all the work they had done, Christophe and Jean, on new electronic interfaces and the role of the performer in relationships to them, Jean will be able to tell you more about these projects in detail.

For a concert in Seoul, I had selected some applications taking account for their framework, sound possibilities, possible developments and I had written a short text as an introduction to the concert, in which we also played other pieces by Xavier.

What I realized almost immediately was the possibility of recreating spaces that were different from those imagined by Xavier, and it was equally possible to work on a kind of “sound intimacy”, because in fact, there’s nothing “demonstrative” about playing with a smartphone, you have to lead the audience to enter in the space you’re proposing, and thanks to the different applications deviating from usual utilization and used in different ways, it was as if I had in front of me a new instrument.

In this case, everything stems from the sound and the space it suggests, and then you need a narrative that will enable you to keep a relatively clear framework, since without this framework you run the risk of going round in circles, and playing the smartphones like a child with a rattle…

As with the Light Wall System[4] also designed by Christophe, the most interesting thing, besides music itself, is the absolute necessity of working on a narration, on a form. This should be obvious to any performer, but which is sometimes forgotten it in favor of the instrument, its virtuosity, its placement on stage…

With the SmartFaust applications,[5] the main aim was to return to a sound devoid of « artifice », that would enable us to invite the audience into a totally revisited sound universe.

After this concert, Christophe had the idea of taking his work with smartphones a step further, and then he proposed to Vincent to imagine a piece for “Smart-Hand-Computers – SHC”, a term that better represents this interface than the word “smartphone” which is primarily used to designate a telephone.

From the outset, however, the process was different than with Xavier, if only in terms of creating the sounds. The fact of having two SHCs totally independent of each other with the possibility to include aleatoric elements in the piece and above all, work on the writing of the piece itself made it a totally different project from anything I had done before. Moreover, this piece is an opportunity for us (Christophe and I) to imagine other performing frameworks: we developed a solo version with a set-up similar to that of the Light Wall System, and we’re working on a project for two dancers. Virtual Rhizome by Vincent-Raphaël Carinola really functions as a permanent laboratory, which incites us to constantly revisit the work, which is essential for a performer. These three proposals around the same piece raise the question of our relationships with the audience: from a) the intimacy of a solo with two SHC, b) to a form of address to the public within the Light Wall System framework, and c) to a choreographic piece in which dancers are at the same time performing the music with their body movements.

This piece enables us to re-examine the act of interpretation, which in itself is an exciting question that performers I think don’t often enough consider.

2.1 Toucher, Theremin and Agencement

Raphaël

Following this first experience we wondered whether it would be interesting to write a work for this “instrument”, bearing in mind that from the moment the theremin is connected to a computer, the instrument is definitively no longer a theremin (the more so since its original sound is never heard). The instrument is the theremin connected to a computer, to sounds and sound processing modules distributed around the audience. This is partly the subject matter of the article « On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music »:[8] here the instrument becomes a playing system. What we consider to be the instrument, the theremin, is just one part of the system, which is in fact the “true” instrument. The theremin is equipped with antennas that capture the performer’s gestures, lamps or electronic circuitry that generate a sound that varies according to the distance of the hands from the antennas and, sometimes, in the same cabinet, a loudspeaker is included. This is like electric guitars, there is a kind of amplifier that can be more or less close to the musician. What interests me here is the possibility to dissociate the organological elements of the instrument and turn each component into a writing support. The performer is then confronted with a sort of fragmented object within a system. On the one hand, the performer has to deal with an instrument very different from the traditional one, since he/she doesn’t control everything because part of the sounds are generated by the computer – so, he/she is playing an instrument that has the ability to function on its own – and, on the other hand, the performer has to follow a score which is not entirely constituted by notation on staves. The score also includes the computer program, which contains the sounds I have generated, integrated into the computer’s memory. So, the score itself is scattered across the whole range of media supports: the graphic score of the gestures, that of sounds, the computer program, the interactive programs, and even the “mapping”, that is, the way in which the interface is correlated with the sounds and with the unfolding of the piece in time.

This is why the performer’s work is quite different from that of a performer who is playing an instrument with which he forms a single body, since with this new instrument – as a system – the body tends to be separated from the direct sound production. One part of the way the instrument functions escapes him/her. The performer doesn’t always control the totality of the sounds (since I am the one who generated them as well as the sound processing modules). Moreover, the computer can also function automatically. That’s what’s so interesting, because it means that the way the performer can adapt to the system becomes in itself an object of creation, the object of the composition, and that’s what’s so beautiful. The performer cannot be considered as someone who appropriates a piece fixed on a support, external to her/him, and which she/he then comes to interpret: he/she is part of the work, one component of this “composed” ensemble of interfaces, the computer, the fixed sounds, him, her, the musician, her/his corporeal presence on stage, etc. We face the same type of problem with Virtual Rhizome but addressed in a very different and very strange way.

Here is the video of the version of Toucher by Claudio Bettinelli :

The fact that the situation in which you find yourself partly escapes us could mean some sort of comfort for the performer, but on the contrary, it really disturbed me. This project allowed me to find myself really at the center, first and foremost as a “listener” before being a performer. This requires concentration, to pay attention to all the sound events that you generate, as well as those that you don’t necessarily control and that you need to appropriate and integrate into your “narrative”.

What makes this attitude more sensitive is the fact that, with these instruments, everything seems simple, because just in relation with a movement. Even though the theremin is extremely technical, each person develops his/her own technique, an attitude linked to a form of inner listening to sound, listening that does not pass exclusively through your ears but also through the body.

Raphaël

In fact, what’s very complicated for me with interactive systems in general is that, if everything is determined, that is if the performer can control each sound produced by the machine, she/he becomes some sort of “operator”. The computer takes no initiative, everything must be determined by conditional logic: if-then-else. The computer is incapable of reacting or adapting to the situation, it only does what it’s asked to do, with a very… binary logic. Everything it does, the way it reacts, is limited by the instructions specified in the software program. That’s why you never have the same relationship with the digital instrument as you do with an acoustic one, in which there is a resistance, a physical constraint, linked to the nature of the instrument, which structures gestures and allows the emergence of expression. That’s why the idea of simulating an instrument that escapes the musician’s control, forces the performer to be in a very attentive listening, to be literally on the look-out, to strain the ear, to charge listening with tension. I think that if you want – I don’t know if it’s possible – to be able to find something equivalent to an expression – when I say “expression”, I don’t mean romantic expression or anything like that, it’s something proper to the musician on stage, to the performer, something that belongs only to him or her – you have to find new ways of making it emerge in interaction with the systems, that’s somewhat the idea of inviting the performer to “stretch the ear”.

2.2 Toucher, Hand/Ear Correlations

Raphaël

Then there’s also the process of interaction, on what actual parameters is it possible to act, a volume, a sound form? From there on, you have your “playground” where the hand can develop its movements, intuitively at first, then by exploring the relationship between sound and gesture to give it a singular form of coherence.

Raphaël

2.3 Toucher, Notation

Ultimately, the question is: should we play what’s written or what we read?

This approach changes things considerably. In many pieces you have introductory notes that resemble more instruction manuals, sometimes they are needed, but they become a problem when there is nothing else besides!

When You read Stockhausen’s Kontakte, even without having read the introductory notice, you’re capable to hear the energies that he wrote in the electroacoustic part. In Toucher, as in Virtual Rhizome, we have a very precise structure, and at the same time sufficient indications to leave the performer free to listen and make the piece his or her own, keeping with the limits set by the composer. It’s really this alloy between a predicted sound and a gesture, an unstable equilibrium… but it’s the same thing with Bach.

With pieces like Vincent’s, it’s essential to have this intimate perception: what do I really want to sing, ultimately, what do I want to be heard, what pleases me about it? If you adopt exactly the same attitude behind a marimba or a violin or a piano, you will really achieve as performer something that will be singular, corresponding to a true appropriation of the text you are reading. The idea is to make people hear and think, just as they do when a poem is read: what will be interesting will be the multiplication of the poem’s interpretations, each one allowing the poem to be always in the making, very much alive. It’s exactly the same with music.

Raphaël

2.4 Toucher, Form

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

2.5 Toucher, Process for Appropriating the Piece

Sidoroff

For me, there’s one thing that’s really incredible, it’s the prescience that you can have of a sound, a prescience that is revealed through an attitude, a gesture, a listening. For Virtual Rhizomes, we don’t always know which texture is going to be played, what impact it will have, and the listening and attention that result from this open up incredible horizons because potentially, it compels us to be even more intuitively aware of our own sound sensations. It’s this balance between the attitude of anticipating integral listening, and the notion of form we’ve been working on, that you need to keep in mind, so as not to get into that famous « rattle » Vincent talks about. It’s interesting to think that a texture played that you don’t know a priori will determine the development of this particular sequence, but you still have to give it a particular meaning in terms of space.

During my last years as percussion professor in Lyon, in order to ensure that this particular attention to sound was an essential part in the work on a piece, I wanted no dynamics to appear on the scores I gave to the students, so that they would just relate to the structure, and that the dynamics (their voice) would be completely free during these first readings. At that point, the question of sound and its projection becomes obvious, whereas if you read a written dynamic sign in absolute terms and therefore decontextualized from a global movement, you don’t even think about it, you just repeat a gesture often without paying sufficient attention to the resulting sound.

On the contrary, Toucher and Virtual Rhizome (like other pieces) force us to question these different parameters. For me, Toucher as Virtual Rhizome, are fundamentally methods of music: there are no prerequisites, except to be curious, interested, aware of possibilities, and present! Such freedom offered by these pieces is first and foremost a way of questioning ourselves at all levels: our relationship to form, sound and space, this is why they are true methods of Music. These pieces are proposing a real adventure and an encounter with oneself. On stage, you know pretty much where you want to go, and at the same time everything remains possible, it’s totally exhilarating and at the same time totally stressful.

Raphaël

Right now, one of my students is practicing the piece. He worked on the available online videos to understand it, to understand its notation, etc., which saves time. But that wasn’t the approach used by Jean, who had another kind of experience. I think that each person deals with it in a certain way. But it’s fair to say that, generally speaking, video has become an accessory to the score.

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, Smartphones, Primitive Rattle, Virtual Spaces

Raphaël

When you’re playing a video game, you might find yourself in a room or on the street, and then at some point you take a turn, you go to another room or to another street, and then you’re attacked by some aliens, you’ve to react, and then you move on to the next stage. It’s a sort of virtual architecture in which you can move in many different ways. This was precisely the idea in Virtual Rhizome, to depart from the traditional instrumental model, which still exists in Toucher, but which is no longer appropriate here because there’s no space to explore with this object that is the smartphone. And from this came the idea of building a virtual space and using the smartphone as an interface, almost like a compass, enabling you find your way around this architecture. That’s how the two things, the rattle, and the video game, are linked together.

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, the Path to Virtuosity: Listening

When I recorded with Vincent the percussion sounds used in Virtual Rhizome, I played almost everything with the fingers, the hands, and that allowed for much more color, dynamics, than if I’d played with sticks. When you’re playing with the hands, there is a particular relationship with the material, especially when you’ve spent your entire life playing with sticks, and in fact, when you’re playing with the hands and fingers your listening is even more “curious”.

Then, in this piece, you need to thoroughly understand the interface and play with it, especially with the possibility of superimposing states that can change with each interpretation. But once again, this is only possible with a clear vision of the overall form, if you don’t want to be overwhelmed by the interface.

Whoever the performer is, there is one common thing, which is this necessity to listen: you hear a sound if you go to the bottom of what it has to say. This means writing an electroacoustic piece in real time, with what you hear inside the sound.

It’s the idea of this interiority that helped develop the interpretation, because at the beginning I was moving a lot on stage, and the more I evolved with the piece, the more intimate, singular and secret this approach became. That’s why on stage there is a counter-light (red if possible) so that the public can only see a shadow, and ideally closes the eyes from time to time…

What’s interesting with the versions with dance is that, ultimately, even if the movements are richer and more diversified, there is really this inner listening that predominates, and forces a certain purity, a choice of intention before the choice of movement, that gives rise with the dancers to totally peculiar listening and embodiment movements.

Raphaël

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, a Collaboration Composer/Performer/Computer Music Programmer

With Vincent, everything seemed coherent and flowing, even when we were recording many sounds over the course of a day. Everything was clear to me, and I quickly understood in what sound universe I was going to evolve in, even though I had no idea of the form of the piece, but just knowing the landscape is an essential thing for the performer.

Raphaël

You raised the question of virtuosity earlier, Jean-Charles. Speaking then of virtuality or virtuosity, I liked the link you made between the two. The virtuosity here resides in the fact that there are two smartphones, behaving in complete isolation from each other. They don’t communicate with each other. You could play the piece with only one smartphone, in a way. You could switch from one situation to another, forwards and backwards, using a gestural control. With both of them, you can combine any situation with any other one. This means that you have to work extremely hard at listening, precisely because, on the one hand you don’t always know what automatized sequences will appear, the textures, the layers mentioned by Jean, and on the other hand, you have also controlled sounds, played, each of which can be very rich in itself. The use of two smartphones implies a great deal of complexity because of the multitude of possible combinations. This requires working intensely on an inner concentrated listening, to orient yourself in this virtual universe, which precisely has no physical consistency. There’s no score anymore, the score is in the head, it’s like the Palace of Memory in the Middle-Ages, a purely virtual architecture that you have to explore. That’s why I like the way you link these terms of virtuosity and of virtuality, because each depends on the other, in a way.

Nowadays, with the presence of set-ups, “agencies” [dispositifs], the notion of writing has completely changed its framework, you have to describe the music and at the same time to develop the electroacoustic set-up process of captation, in real time, that is, building an instrument.

The composer can only partly cover the second third, bearing in mind that lutherie also evolves in the writing process… The only obvious thing is that from beginning to end, there is a spoken word, that of the composer, in terms of: “This I want, that I don’t want”. And for me, this is the alpha and omega of creation, that is, its requirement. The composer provides us, performers, with a material, a discourse, a narrative, a vision, a relevance. It’s not a question of hierarchy, but this kind of spoken word is at the heart of the whole process of encounter and creation.

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, the « Score »

Raphaël

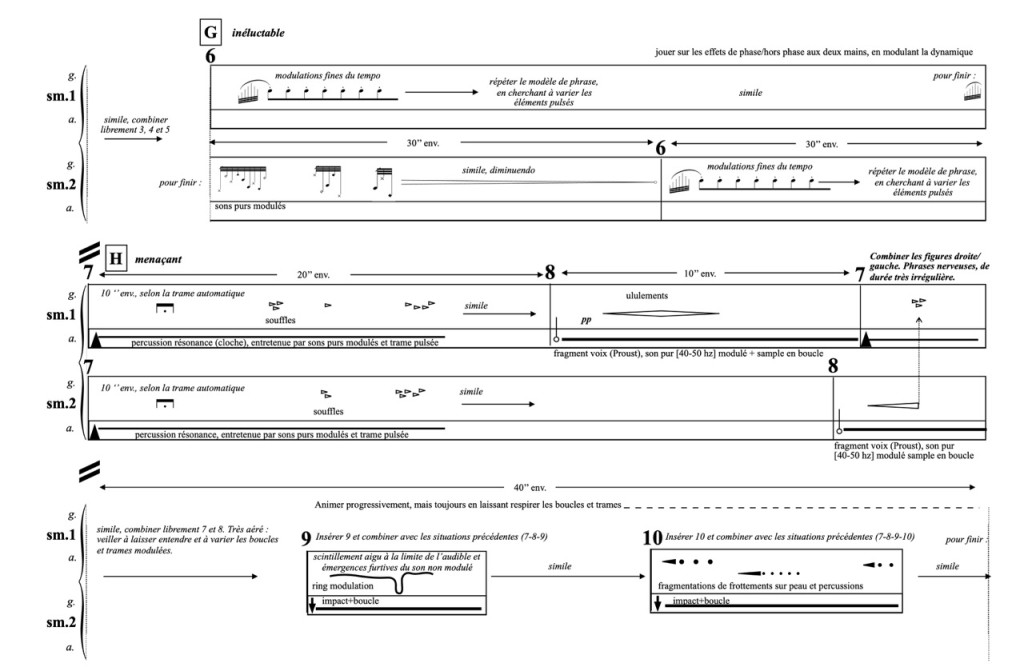

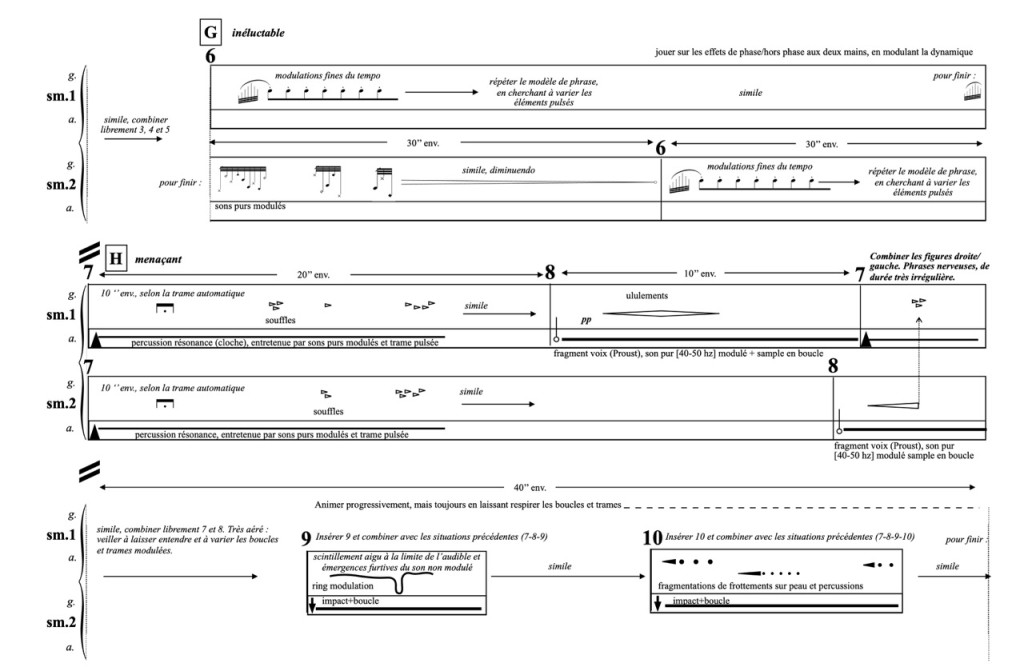

At the top of Figure 3, there’s also a word: “ineluctable”. These terms have been added to produce intentionality. The performer doesn’t just generate sounds, she/he animates them, gives them a soul, literally, and to give them a soul requires an intention, a meaning. It might be a concept, I don’t know, a geometric figure, something that generates intentionality. This is important in the score, but what is notated is actually a possible pathway, and this is the result therefore of the performer’s work, it’s a pathway followed by the performer during the collaboration, and which becomes a possible model for the piece’s realization. It’s interesting to note that it is this pathway that was followed by other performers who played it, as if the form was definitively fixed.

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

3.5 Conclusion: References to André Boucourechliev and John Cage

Raphaël

Raphaël

1.Christophe Lebreton : « Musicien et scientifique de formation, il collabore avec Grame depuis 1989. » Musician and educated as a scientist, he collaborates with Grame since 1989.

See: Grame

2. Xavier Garcia, musician, Lyon : Xavier Garcia

3. Charles Juliet, Rencontres avec Bram Van Velde, P.O.L., 1998.

4. « Light Wall System was developed in LiSiLoG by Christophe Lebreton and Jean Geoffroy. See LiSiLoG, Light Wall System

5. SmartFaust is both the title of a participatory concert and the name of a set of applications for smartphones (Android and Iphone) developed by Grame using the Faust language. See Grame, Smart Faust.

6. Claudio Bettinelli, percussionist, Saint-Etienne. See Claudio Bettinelli.

7. Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Typhon, the work is inspired by Joseph Conrad’s story Typhon. See Grame, Typhon.

8. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, 2.3, 2nd paragraph.

9. Thierry De Mey, Silence Must Be: “In this piece for solo conductor, Thierry De Mey continues his research into movement at the heart of the musical ‘fact’… The conductor turns towards the audience, takes the beat of his/her heart as pulsation and begins to perform increasingly complex polyrhythms, …3 on 5, 5 on 8, getting close to the golden ratio, she/he traces the contours of a silent, indescribable music…”. Grame

10. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, op. cit. 3.1.

11. Thierry de Mey, Light music: “musical piece for a ‘solo conductor’, projections and interactive device (first performance March 2004 – Biennale Musiques en Scène/Lyon), performed by Jean Geoffroy, was produced in the Grame studios in Lyon and at the Gmem in Marseille, where Thierry De Mey was in residence.” Grame

12. Jorge Luis Borges, Fictions, trad. P. Verdevoye et N. Ibarra, Paris : Gallimard, 1951, 2014.

13. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, op. cit. 3.2.

14. See Monique David-Ménard, « Agencements déleuziens, dispositifs foucaldiens », in Rue Descartes 2008/1 (N°59), pp. 43-55 : Rue Descartes

Vincent Raphaël Carinola et Jean Geoffroy

La contribution de Vincent-Raphaël Carinola et Jean-Geoffroy est en deux parties. D’une part un article de recherche, « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives », initialement publié en anglais sous le titre “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”, by Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean Geoffroy, dans le actes du colloque organisé par PRISM-CNRS à Marseille (en mai 2022). D’autre part la transcription d’une rencontre entre Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Jean Geoffroy, Jean-Charles François et Nicolas Sidoroff qui a eu lieu en février 2023 à Lyon.

Accès aux deux parties et à leurs versions en anglais :

Première partie

Accès à l’article « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives »

Access to the original English version of “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”

Deuxième partie

Rencontre avec Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff

Access to the English translation of « Encounter with Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff »

Rencontre avec

Jean Geoffroy, Vincent-Raphaël Carinola

et

Jean-Charles François, Nicolas Sidoroff

1er février 2023

Sommaire :

1. Origines de la collaboration

2.1 Toucher Thérémine et Agencement

2.2 Toucher, l’exigence d’une corrélation mains/oreille

2.3 Toucher, notation

2.4 Toucher, la forme

2.5 Toucher, processus temporel de l’appropriation de la pièce

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, smartphones, hochet primitif, espaces virtuels

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, le chemin vers la virtuosité, l’écoute

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, une collaboration compositeur/interprète/réalisateur en informatique musicale

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, la « Partition »

3.5 En conclusion : Références à André Boucourechliev et John Cage

1. Origines de la collaboration

François

Raphaël

Carinola

Lors d’un concert à Séoul, j’avais fait une sélection des applications en prenant en compte leurs cadres, possibilités sonores, leurs développements possibles et j’avais écrit une forme courte en guise d’introduction au concert dans lequel nous avions également joué d’autres pièces de Xavier.

Ce dont je me suis rendu compte presque immédiatement c’est qu’il était possible de recréer des espaces différents de ceux imaginés par Xavier, il était également possible de travailler sur une sorte « d’intimité sonore » car en effet il n’y a rien de « démonstratif » dans le jeu que l’on peut avoir avec un smartphone, il faut amener le public à entrer dans l’espace qu’on lui propose, et grâce aux différentes applications prise dans un autre sens et surtout utilisées de façon différentes, c’est comme si j’avais devant moi un nouvel instrument.

Dans ce cadre, tout part du son et de l’espace qu’il suggère, ensuite il faut une narration qui nous permettra de garder un cadre relativement clair car sans ce cadre nous risquerions de tourner rapidement en rond et jouer avec les smartphones comme un enfant avec son hochet…

Comme pour le Light Wall System[4] également créé par Christophe, le plus intéressant en dehors de la musique en elle-même, c’est la nécessité absolue d’un travail sur une narration, sur une forme, chose qui devrait être évidente pour tout interprète, mais que parfois on oublie au profit de l’instrument, sa virtuosité, sa place sur scène…

Avec les applications SmartFaust[5], il s’agissait avant tout de retrouver un son sans « artifices » qui nous permettrait de convoquer le public dans un univers sonore totalement revisité.

Ensuite après ce concert Christophe a eu l’idée d’aller plus loin dans ce travail avec les smartphones et donc c’est à ce moment qu’il a proposé à Vincent d’imaginer une pièce pour « Smart-Hand-Computers – SHC », terme qui représente mieux cette interface que le mot « smartphone » qui est avant tout utilisé pour nommer un téléphone.

Par contre dès le début, le processus a été différent qu’avec Xavier, ne serait que pour la création des sons, le fait d’avoir deux SHC totalement indépendants l’un de l’autre, avec une écriture intégrant des propositions aléatoires et surtout un travail sur l’écriture de la pièce elle-même en faisait un projet totalement différent de ce que j’avais fait auparavant. De plus cette pièce est pour nous (Christophe et moi) l’occasion d’imaginer d’autres cadres interprétatifs : nous avons une version solo avec un dispositif qui ressemble à celui du Light Wall System, et nous travaillons à une proposition pour deux danseurs. Virtual Rhizome de Vincent-Raphaël Carinola fonctionne vraiment comme un laboratoire permanent, qui nous incite à des relectures permanentes ce qui est essentiel pour un interprète. En effet ces trois propositions autour d’une même pièce questionne notre rapport au public : a) de l’intime en solo avec deux SHC ; b) dans une forme d’adresse au public dans le cadre du dispositif LWS ; et c) dans le cadre d’une pièce chorégraphique dans laquelle les danseurs seraient en même temps les interprètes de la musique qu’ils incarnent.

Cette pièce permet de requestionner l’acte interprétatif ce qui en soit est passionnant, question que l’on ne se pose pas assez en tant qu’interprète je trouve.

2.1 Toucher, Thérémine et Agencement

Raphaël

À la suite de cette première expérience on s’est demandé s’il ne serait pas intéressant d’écrire carrément une œuvre pour cet « instrument », sachant qu’à partir du moment où le thérémine est connecté à l’ordinateur, l’instrument n’est plus le thérémine (d’autant plus qu’on n’en entend jamais le son). L’instrument, c’est le thérémine connecté à l’ordinateur, à des sons et des modules de traitement sonore diffusés autour du public. C’est d’ailleurs en partie le sujet de l’article « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives » qu’on pourra trouver dans la présente édition : l’instrument devient un dispositif de jeu. Ce que nous considérons comme étant l’instrument, le thérémine, c’est juste une partie du dispositif, lequel est de fait le « vrai » instrument. Le thérémine possède des antennes qui captent les gestes de l’interprète, des lampes ou des circuits électroniques qui génèrent un son variant en fonction de la distance des mains par rapport aux antennes et, parfois, dans le même meuble, un haut-parleur. C’est comme les guitares électriques, il y a une sorte d’ampli, qui peut être plus ou moins près du musicien. Ce qui m’intéresse là-dedans, c’est qu’on peut dissocier les éléments organologiques de l’instrument pour faire de chaque composante un support d’écriture. L’interprète est alors confronté à une sorte d’objet éclaté dans un dispositif. L’interprète fait face, d’une part, avec un instrument très différent de l’instrument traditionnel, puisqu’il ne contrôle pas tout, il y a une partie des sons qui est générée par l’ordinateur — il joue donc d’un instrument qui a la capacité de fonctionner tout seul — et, d’autre part, il doit suivre une partition qui n’est pas entièrement constituée de la notation sur les portées. La partition inclut aussi le programme informatique, et contient les sons que j’ai fabriqués, intégrés dans la mémoire de l’ordinateur. Donc, la partition elle-même se trouve éclatée dans l’ensemble de supports : la partition graphique des gestes, celle des sons, le programme informatique, les programmes interactifs, et même le « mapping », c’est-à-dire la façon dont on va corréler l’interface aux sons et au déroulé de la pièce.

C’est pourquoi le travail de l’interprète est assez éloigné de celui de l’interprète qui a à faire avec un instrument avec lequel il fait corps, car, avec cet instrument nouveau qu’est le dispositif, le corps tend à être séparé de la production directe des sons. Une partie du fonctionnement de l’instrument lui échappe. Il ne contrôle pas toujours tous les sons (puisque c’est moi qui les ai fabriqués, ainsi que les modules de traitement). En plus, l’ordinateur peut avoir un fonctionnement automatique. C’est ça qui est intéressant, justement, parce que ça veut dire que la façon d’agencer l’interprète à ce dispositif-là devient en elle-même un objet de création, l’objet du travail de composition, c’est ça qui est très beau. On ne peut pas considérer l’interprète comme quelqu’un qui s’approprie une pièce fixée à un support, extérieure à lui, et qu’il vient ensuite interpréter : il fait partie de l’œuvre, il est une composante de cet ensemble « composé » des interfaces, de l’ordinateur, les sons fixés, lui, le musicien, sa présence corporelle sur scène, etc. On a le même type de problématique, mais abordée d’une façon très différente et très étrange avec Virtual Rhizome.

Voici la vidéo de la version de Toucher par Claudio Bettinelli :

Le fait que la situation dans laquelle nous nous trouvons nous échappe en partie, car loin d’être confortable cette situation me perturbait vraiment. Ce projet m’a permis de me retrouver réellement au centre, avant tout comme « écoutant » avant d’être interprète. Cela oblige à une concentration, une attention à tous les événements sonores que nous générons ainsi que ceux que nous ne contrôlons pas forcément et que nous devons nous approprier et intégrer à notre « narration ».

Ce qui rend cette attitude plus sensible, c’est le fait que pour ces instruments tout parait simple car juste en relation avec un mouvement. Même si le Thérémine est extrêmement technique, chacun développe sa propre technique, attitude reliée à une forme d’écoute intérieure du son, écoute qui ne passe pas exclusivement par nos oreilles mais également par le corps.

Raphaël

2.2 Toucher, l’exigence d’une corrélation mains/oreille

Raphaël

Il y a ensuite le travail d’interaction, sur quoi agit-on réellement, un volume, une forme sonore, quels sont les paramètres sur lesquels nous agissons ? À partir de là nous avons notre « aire de jeu » et la main peut s’y développer, tout d’abord de façon intuitive.

Raphaël

2.3 Toucher, Notation

La question au final est : doit-on jouer ce qui est écrit ou ce qu’on lit ?

Cette approche change énormément de choses. Il y a beaucoup de pièces où vous avez des notes de programmes, qui ressemblent plus à des modes d’emplois, parfois nécessaire mais cela devient problématique lorsqu’il n’y a rien côté !

Lorsque l’on lit Kontakte de Stockhausen même sans avoir lu la notice, on est capable d’entendre les énergies qu’il a écrit dans la partie électroacoustique. Dans Toucher, comme dans Virtual Rhizome, nous avons une structure très précise, et en même temps, suffisamment d’indications pour laisser une liberté d’écoute de l’interprète pour s’approprier la pièce, dans les proportions qui sont celles données par le compositeur. C’est vraiment cet alliage entre un son pressenti et un geste, équilibre instable… mais c’est la même chose chez Bach.

Il est essentiel à travers des pièces comme celles de Vincent d’avoir cette perception intime : qu’est-ce que j’ai envie de chanter, finalement, qu’est-ce que j’ai envie de faire entendre, qu’est-ce qui me plaît là-dedans ? Si on adopte exactement la même attitude derrière un marimba ou un violon ou un piano, l’interprète va vraiment réaliser quelque chose qui sera singulier et qui correspondra à une vraie appropriation du texte qu’il est en train de lire. Il s’agit de faire entendre et penser comme lorsque l’on entend la lecture d’un poème : ce qui sera intéressant ce sera la multiplication des interprétations du poème, chacune permettant au poème d’être toujours en devenir, bien vivant. C’est exactement la même chose pour la musique.

Raphaël

2.4 Toucher, la forme

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

2.5 Toucher, processus temporel de l’appropriation de la pièce

Sidoroff

Une chose est pour moi réellement incroyable c’est la préscience que l’on peut avoir d’un son, préscience qui se révèle à travers une attitude, un geste, une écoute. Pour Virtual Rhizomes, on ne sait pas toujours quelle nappe va être jouée, quel impact, et l’écoute, l’attention qui en découle nous ouvre des horizons incroyables car potentiellement, cela nous oblige à être encore plus dans l’intuition d’un ressenti sonore qui nous est propre. C’est cet équilibre entre cette attitude d’écoute intégrale anticipée, et la notion de la forme sur laquelle nous avons travaillé qu’il faut garder de façon à ne pas être dans ce fameux « hochet » dont parle Vincent. Il est intéressant de se dire qu’une nappe jouée et que l’on ne connait pas à priori va déterminer le développement de cette séquence particulière, encore faut-il lui donner un sens particulier en termes d’espace.

Les dernières années où j’étais professeur de percussion à Lyon, pour faire en sorte que cette attention particulière au son soit mise en évidence dans le travail d’une pièce, je voulais qu’aucune nuance n’apparaisse sur les partitions que je donnais aux étudiants uniquement pour qu’ils aient un rapport simplement à la structure, et que les dynamiques (leur voix) soient lors de ces première lectures totalement libres. A ce moment-là, se pose de manière évidente la question du son et de sa projection, alors que si on lit une nuance écrite dans l’absolu et donc décontextualisée d’un mouvement global, on n’y pense même pas, on répète un geste sans que l’on prenne souvent suffisamment attention au son qui en résulte.

A l’inverse Toucher et Virtual Rhizome (comme d’autre pièces) nous obligent à questionner ces différents paramètres. Pour moi, Toucher comme Virtual Rhizome, sont fondamentalement des méthodes de musique : pas de prérequis, sauf à être curieux, intéressé, conscient des possibles, présent ! Cette liberté que nous proposent ces pièces sont avant tout une façon de nous questionner à tous les niveaux : notre rapport à la forme, au son, à l’espace, c’est en cela qu’elles sont de réelles méthodes de Musique. Ces pièces sont une véritable aventure et rencontre avec soi. Sur scène, vous savez à peu près où vous voulez aller, et en même temps, tout reste possible, c’est totalement grisant et en même temps totalement stressant.

Raphaël

En ce moment un de mes étudiants est en train de monter la pièce. Il a travaillé sur les vidéos qu’on peut trouver en ligne pour la comprendre, en comprendre la notation, etc., ce qui fait gagner un peu de temps. Mais cela n’a pas été la démarche de Jean, il a eu un autre type d’expérience. Je pense que chacun aborde la pièce d’une certaine manière. Mais on peut dire que de façon générale, la vidéo est devenue un accessoire à la partition.

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, smartphones, hochet primitif, espaces virtuels

Raphaël

Quand tu joues à un jeu vidéo, tu peux te retrouver dans une pièce ou dans la rue, puis à un moment donné tu tournes, tu vas dans une autre pièce ou tu passes dans une autre rue, et puis tu as des extraterrestres qui t’attaquent, tu dois réagir et ensuite tu passes à l’étape suivante. C’est une sorte d’architecture virtuelle que tu peux parcourir de plein de façons différentes. Finalement c’était ça l’idée dans Virtual Rhizome, laisser tomber le modèle instrumental traditionnel, qui existe encore dans Toucher, mais qui n’est plus adapté ici parce qu’il n’y a pas d’espace à explorer dans cet objet qu’est le smartphone. Et de là est venu cette idée de construire un espace virtuel et d’utiliser le smartphone comme une interface, presque comme une boussole qui permet de s’orienter à l’intérieur de cette architecture. Voilà comment les deux choses, le hochet et le jeu vidéo, sont liées.

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, le chemin vers la virtuosité, l’écoute

Lorsque l’on a enregistré avec Vincent les sons de percussion utilisés dans Virtual Rhizome, je jouais quasiment tout avec les doigts, les mains, cela permettait d’avoir beaucoup plus, de couleurs, de dynamique que si j’avais utilisé des baguettes. Lorsque l’on joue avec les mains il y a un rapport à la matière qui est particulier, surtout lorsque l’on passe sa vie à jouer avec des baguettes, et de fait, notre écoute lorsque l’on joue avec les mains et les doigts est encore plus « curieuse ».

Ensuite, pour cette pièce, il s’agit de bien comprendre l’interface et en jouer notamment avec la possibilité de superpositions d’états que l’on peut changer à chaque interprétation. Mais encore une fois, cela n’est possible qu’avec une vision claire de la forme générale si on ne veut pas se laisser dépasser par l’interface.

Quelque-soit l’interprète, il y a un point commun qui est cette nécessité d’écouter ; un son est entendu si je vais jusqu’au bout de ce qu’il peut dire. Il s’agit d’écrire une pièce électroacoustique en temps réel, avec ce qu’on entend de l’intérieur du son.

C’est l’idée de cette intériorité qui a fait avancer l’interprétation car au début je bougeais beaucoup sur scène, et plus j’ai avancé dans la pièce plus cette démarche est devenue intime, singulière et secrète, c’est pour cela que sur scène je suis éclairé par un contre (si possible rouge) pour que le public ne voit qu’une ombre et idéalement ferme de temps en temps les yeux…

Ce qui est intéressant avec les versions avec danse c’est qu’au final même si les mouvements sont plus riches plus diversifiés, il y a vraiment cette écoute intérieure qui prédomine et qui contraint à une certaine épure, un choix de l’intention avant le choix du mouvement ce qui donne à voir avec les danseurs des mouvements d’écoute et d’incarnation totalement singuliers.

Raphaël

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, une collaboration

compositeur/interprète/réalisateur en informatique musicale

Avec Vincent tout parait cohérent et fluide même lorsque nous avons enregistré des tas de sons pendant une journée. Tout était clair pour moi et rapidement j’ai compris dans quel univers sonore j’allais évoluer, même si je n’avais pas idée de la forme de la pièce, mais rien que de connaître le paysage est une chose essentielle pour un interprète.

Raphaël

Tu as posé une question tout à l’heure, Jean-Charles, sur la virtuosité. Alors parler de virtualité ou de virtuosité, j’ai bien aimé le lien que tu fais entre les deux. La virtuosité, ici, réside dans le fait qu’il y a deux smartphones ayant un comportement complètement isolé l’un de l’autre. Ils ne communiquent pas entre eux. On pourrait jouer l’œuvre avec un seul smartphone, d’une certaine façon. On passerait d’une situation à l’autre, en avant et en arrière, grâce au contrôle gestuel. Avec les deux, on peut combiner n’importe quelle situation avec n’importe quelle autre situation. Ça veut dire qu’il faut un travail d’écoute, là, pour le coup, extrêmement tendu justement, du fait que, d’une part, tu ne sais pas toujours quelles sont les séquences automatisées qui vont apparaître, les trames, les nappes dont parlait Jean et d’autre part, tu as aussi les sons contrôlés, joués, dont chacun peut être très riche déjà en soi. Les deux smartphones induisent une très grande complexité du fait de la richesse des combinaisons possibles. Cela demande un travail d’écoute, d’intériorité, très concentré pour tenter de se repérer dans cet univers virtuel, car, justement, il n’a pas de consistance physique. Il n’y a plus de partition, la partition est dans la tête, c’est comme le palais de mémoire au moyen-âge, une architecture purement virtuelle qu’il faut parcourir. Ce qui fait que j’aime bien que tu rattaches ces termes de virtuosité et de virtualité parce que l’un dépend de l’autre, d’une certaine façon.

De nos jours, avec les dispositifs, la notion d’écriture a totalement changé de cadre, il s’agit en même temps de décrire la musique tout en mettant en place le dispositif de captation ou électroacoustique, ou en temps réel, c’est-à-dire construire un instrument.

Le compositeur ne peut couvrir qu’en partie le 2ème tiers sachant que la lutherie évolue également dans le processus d’écriture… La seule chose qui est évidente, c’est que du début à la fin, il y a une parole, c’est celle du compositeur, en termes de : « Ça je veux, ça je ne veux pas ». Et pour moi, c’est l’alpha et l’oméga de la création, c’est-à-dire son exigence. En tant qu’interprète il nous fait une matière, un discours, un récit, une vision, une pertinence. Il ne s’agit pas de hiérarchie, mais cette parole-là est le cœur de tout le processus de rencontre et de création.

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, la « Partition »

Raphaël

Au-dessus, dans la Figure 3, il y a aussi un terme : « inéluctable ». Il y a des termes qui sont venus s’ajouter afin de produire des intentionnalités. L’interprète ne fait pas que générer des sons, il les anime, leur donne une âme, littéralement, et pour leur donner une âme, il faut qu’il y ait une intention, un sens. Ça peut être un concept, je ne sais pas, une figure géométrique, quelque chose qui génère une intentionnalité. Ceci est important dans la partition, mais ce qui est noté c’est effectivement un parcours possible, et celui-là résulte donc du travail de l’interprète, c’est un parcours qui a été effectué par l’interprète pendant la collaboration et qui devient un modèle de la pièce possible. Il est intéressant de constater que c’est ce parcours qui a été suivi par les autres interprètes qui l’ont jouée, comme si la forme était définitivement fixée.

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

3.5 En conclusion : Références à André Boucourechliev et John Cage

Raphaël

Raphaël

1.Christophe Lebreton : « Musicien et scientifique de formation, il collabore avec Grame depuis 1989. »

Voir : Grame

2. Xavier Garcia, musicien, Lyon : Xavier Garcia

3. Charles Juliet, Rencontres avec Bram Van Velde, P.O.L., 1998.

4. « Light Wall System a été développé par LiSiLoG avec Christophe Lebreton et Jean Geoffroy. Voir LiSiLoG, Light Wall System

5. « SmartFaust est à la fois le titre d’un concert participatif, et le nom d’un ensemble d’applications pour smartphones (Android et Iphone) développées par Grame à partir du langage Faust. » Voir Grame, Smart Faust.

6. Claudio Bettinelli, percussionniste, Saint-Etienne. Voir Claudio Bettinelli.

7. Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Typhon, l’œuvre s’inspire du récit de Joseph Conrad Typhon. Voir Grame, Typhon.

8. « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives », op. cit. 2.3, 2e paragraphe.

9. Thierry De Mey, Silence Must Be : « Dans cette pièce pour chef solo, Thierry De Mey poursuit sa recherche sur le mouvement au cœur du « fait » musical… Le chef se tourne vers le public, prend le battement de son cœur comme pulsation et se met à décliner des polyrythmes de plus en plus complexes ; …3 sur 5, 5 sur 8, en s’approchant de la proportion dorée, il trace les contours d’une musique silencieuse, indicible… » Grame

10. « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives », op. cit. 3.1.

11. Thierry de Mey, Light music : « pièce musicale pour un « chef solo », projections et dispositif interactif (création mars 2004 – Biennale Musiques en Scène/Lyon), interprétée par Jean Geoffroy, a été réalisée dans les studios Grame à Lyon et au Gmem à Marseille, qui ont accueilli en résidence Thierry De Mey. » Grame

12. Jorge Luis Borges, Fictions, trad. P. Verdevoye et N. Ibarra, Paris : Gallimard, 1951, 2014.

13. « Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives », op. cit. 3.2.

14. Voir Monique David-Ménard, « Agencements déleuziens, dispositifs foucaldiens », dans Rue Descartes 2008/1 (N°59), pp. 43-55 : Rue Descartes