The Body Weather Farm (1985-90 period)

Encounter with

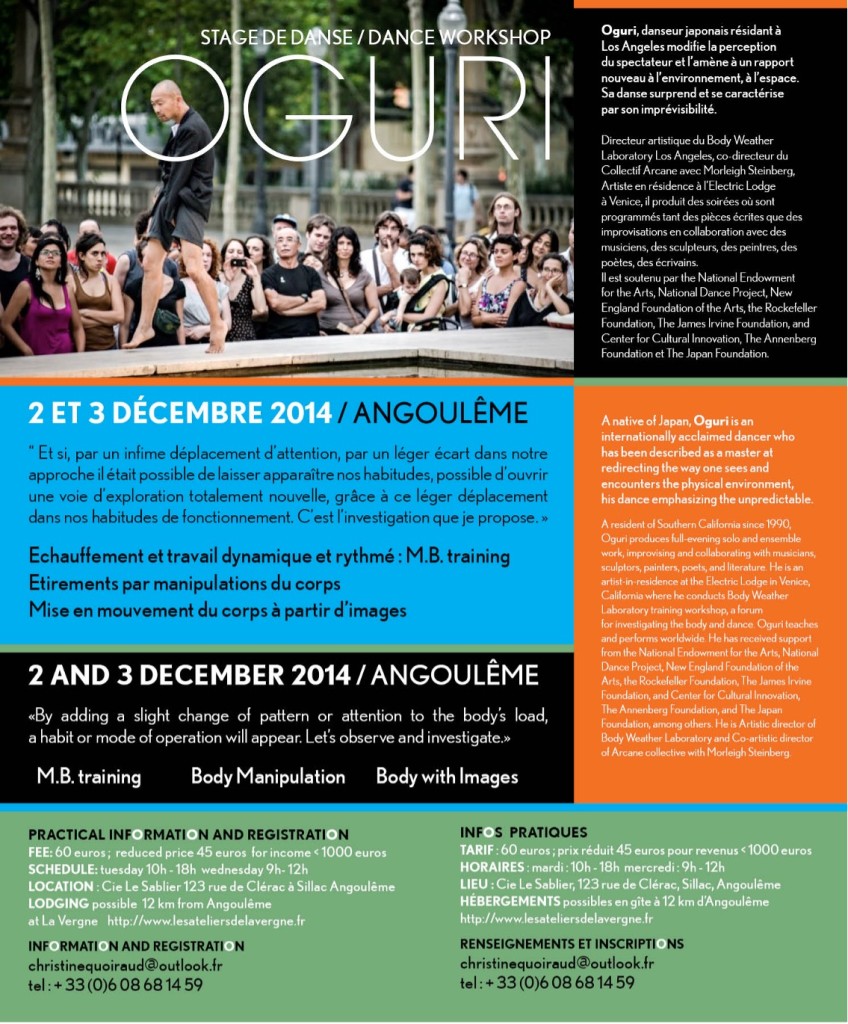

Christine Quoiraud, Katerina Bakatsaki, Oguri

With the participation of Jean-Charles François

and Nicolas Sidoroff for PaaLabRes

2022-23

Summary :

1. Introduction.

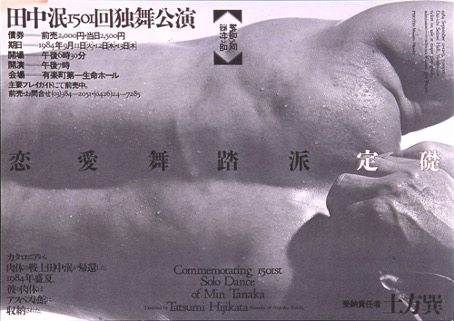

2. Before the Body Weather Farm, the encounter with Min Tanaka.

3. Maï-Juku V and the beginning of the farm. Tokyo-Hachioji-Hakushu.

4. Body Weather, the farm, and the dance.

5. The commons within Body Weather.

6. Choreography, improvisation, images.

7. Relationships to music.

8. Conclusion. After the Body Weather farm.

1. Introduction: Presentation of the Encounters.

The origin of this text stems from a first encounter in Valcivières (a village in the Forez, France) in 2020, as part of CEPI (Centre Européen Pour l’Improvisation) between Christine Quoiraud and Jean-Charles François. On this occasion, Christine Quoiraud presented an illustrated lecture on Body Weather, her own activities firstly called Body/Landscape (“Corps/Paysage”), and her improvised long marching journeys for dancers and non-dancers (called “Marche et Danse”). In the perspectives of the fourth edition of the PaaLabRes collective, the precise documentation of the diverse practices that had taken place during Christine’s presence at the Body Weather farm in Japan (1985-90) appeared to be of great importance. Many critical points remained to be clarified after this presentation, notably concerning:

- The relationships between the activities of everyday life at the farm, the practices of cultivating the land, of raising animals, with the artistic practices.

- The relationships between the various participants committed to the farm project.

- The relationships with nearby farmers.

- The relationships between dance and the environment.

- The relationships between dance and music.

Christine suggested to PaaLabRes to organize an encounter by videoconference with dancers, ex-members of Maï-Juku, Katerina Bakatsaki, living in Amsterdam, Oguri, living in Los Angeles, herself, living in south-west of France, and for PaaLabRes in Lyon, Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff.

Two encounters with all these people took place by videoconference on May 31, 2022, and February 15, 2023. In between these two interviews, Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff formulated in writing a series of questions. We decided that the questions asked by PaaLabRes would not appear in the present text, except as short introductions to the various sections of the document.

The recording of the oral exchanges in English during the two interviews have been transcribed (with the precious help of Christine Quoiraud) by Jean-Charles François and translated into French. The original English verbatim has been edited to make it clearer for readers, but wherever possible, we tried to preserve the oral nature of the exchanges. We thank the Centre National de la Danse (CND) for allowing us to publish the photos from the Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque.

The different sections do not automatically follow the chronological order of the two interviews but are based on the principal themes discussed in a specific logical progression.

2. Before the Body Weather farm, meeting Min Tanaka.

Presentation

Katerina Bakatsaki, Oguri, and Christine Quoiraud are three dance artists who, from 1985 to 1990, had in common their participation in the Body Weather farm created by Min Tanaka and Kazue Kobata a hundred kilometers from Tokyo.

In order to situate their approach and provide insight into their initial careers, this introductory part is devoted to the circumstances that led them to meet Min Tanaka prior to their participation in the farm.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

You can all see me laughing, of course, because it happened so long ago. It’s been quite a journey. Now that we’re all in different phases of our lives, I have mixed feelings about my memory of those circumstances, so it’s best to laugh about it. But to answer straight away to your question, I can tell you that when I first went to Japan, I was twenty-one years old. I had no clue of what was ahead of me. I met Min Tanaka around 1985, he was dancing at La MaMa Theater Club near New York, and Œdipus Rex was presented with Min being the choreographer. A performance of Œdipus Rex also took place in Athens, and for that production they needed local artists to paticipate, so I had the chance and pleasure to be selected. That’s how I got involved in the production and this is how I got to meet Min and his way of working. 1985, twenty-one years old! You can imagine a young horse knowing that there are several possible paths, but without knowing exactly what it needs and wants, because simply of a lack of information. In 1985, we didn’t know exactly in Greece what « contact improvisation » was, we’d only vaguely heard about it, so information about what was going on in the world was very, very rare, if at all existent. So, I was curious, I’d just started to dance in Greece at the time, but I was looking for something else and without knowing exactly what it was, I was travelling in Europe, meeting different choreographers, having auditions. I met Pina Bausch, I could have joined her company, but I didn’t because intuitively I thought no, it wasn’t for me. So, I was curious, I’d just started to dance in Greece at the time, but I was looking for something else and without knowing exactly what it was, I was travelling in Europe, meeting different choreographers, having auditions. Anyway, I met Min in that production, and, I think, before and above anything else, there was something that I strongly believed in intuitively, that I trusted, or that I could connect with, but I still didn’t know what it was. Whatever it was, I thought, “Well, I want to know what this person is doing”. And at that time, he mentioned to me that he was conducting two-month workshops in Japan, so, I thought “I am going!” Just a funny anecdote: I took my pointe shoes with me – I was a student at the time and part of my studies was classical ballet – just to give you an idea how clueless I was. So, I landed in the studio in Hachioji, the farm was not founded yet. So, going to the farm was a consequence of being part of the practice in the community at that time, before the farm came into existence. By the way, I went there in 1985 for two months and then I stayed for eight years.

Oguri:

So… maybe it’s my turn… Let’s start. So – I am laughing! – it was thirty years ago! Thirty years ago, I left also everything behind, I was there five years, same years as Katerina and Christine. Like Katerina said, there was a two-month workshop: “Maï-Juku V, an intensive workshop”. Min Tanaka started this series in 1980. OK, I’m going back a bit: I lived in Tokyo. I wasn’t born there, I studied visual arts – a kind of conceptual art – with Genpei Akasegawa. He passed away in 2014. He was a very important name at that time in the art’s scene in Japan. When, in the 1960s, so before Japan had a big world expo in the 1970s in Osaka, and before that he was a non-established artist, he met the movement of the Neo-Dada organizers at the Hi-Red Center and collaborated a lot with Nam June Paik and John Cage. Anyway, I was interested in studying with that kind of visual arts. And during the 1960s, Akasegawa collaborated extensively with Hijikata Tatsumi[1] as part of the Japanese Ankoku Butōh movement. Studying with Akasegawa, I was introduced to all avant-garde work of the sixties (see Akasegawa Genpei Anatomie du Tomason). And Butōh, Ankoku Butōh was very attractive. But I wasn’t really ready to become a dancer. And in the 1980s, when I was still studying, I also saw Min Tanaka’s work. He was still dancing then with a shaved head and naked body, painted, with very gradual slow movements and longtime performances. And he worked with Milford Graves and Derek Bayley, this was a big event in Tokyo. Very strong impression for me, being something “in between”, was it dance? And actually, at that time, the term “performance” was introduced in Japan. Not “performance art”, just “performance”. What is a “performance”, what is a Butōh, and what is dance? That boundary, it’s impossible for me to define: small theater? The idea of theater became popular from the 1960s on. But it’s not a new type of a theater either, it’s all like a melting pot. At that time, I took Hijikata Tatsumi’s Butōh Workshop. It was very short, maybe a three-day intensive. That was what I got as dance training before participating in Min Tanaka’s Body Weather work. I never had a formal dance training background. I had seen Butōh and Min Tanaka’s work and I took part in a performance. But I wasn’t a dancer yet. During the first Butōh festival in Japan, in Tokyo. Min brought together forty male dancers, male bodies. This performance was my first participation. Then a year after, yes, I got some flyer advertising the intensive workshop Maï-Juku. That’s where my work with this practice really began. So, yes, actually in 1985, during Maï-Juku V, I was also involved in the preparation of the Body Weather farm in Hakushu. So, it’s kind of a parallel project: it was the start of preparing the place, the farm, and taking part in Maï-Juku V. And once Maï-Juku V started, I think, after one month, we moved, we had a separate training in the farm. I remember what we did in a waterfall… Before the Maï-Juku V, Min Tanaka didn’t have a performance group. Maï-Juku’s concept was collecting bodies – no, not the body – the “capture” of the people participating in the training: when Min Tanaka was touring, that’s how Katerina was caught. In Europe and the U.S., La MaMa and always touring, he had performances and teaching workshops… so it’s like two wheels, and the people were interested and participated every year. So Maï-Juku I to V. In the fifth year, they started Maï-Juku Dance Troup for doing performance work. In that time, they didn’t call what they were doing Butōh or dance performance, but it was called “Maï-Juku performance”. And regarding this Maï-Juku V year, when we participated, it was a big, big turning point. Many of the former Maï-Juku members had left. It was a very strange moment. At the beginning, I believe we had about forty people who participated the first two months. After the two months of intensive training, I think we were left with only ten people or something. But ten people stayed. Ten people may be including about two or three from Japan. So, a number of European people stayed, like Katerina, Christine, Tess de Quincey from Australia, Frank van de Ven from Holland, and (in 1986) Andres Corchero and Montse Garcia from Spai – a few people.[2] It was a big transition, Yes, I think that when Min Tanaka started the farm, this transition was a big issue. He never named his dance as Butōh, but in 1984, Min danced Hijikata’s choreography, he performed his solo dance. That was also a big turning point, changing the… Yes, ok. I stop talking now.

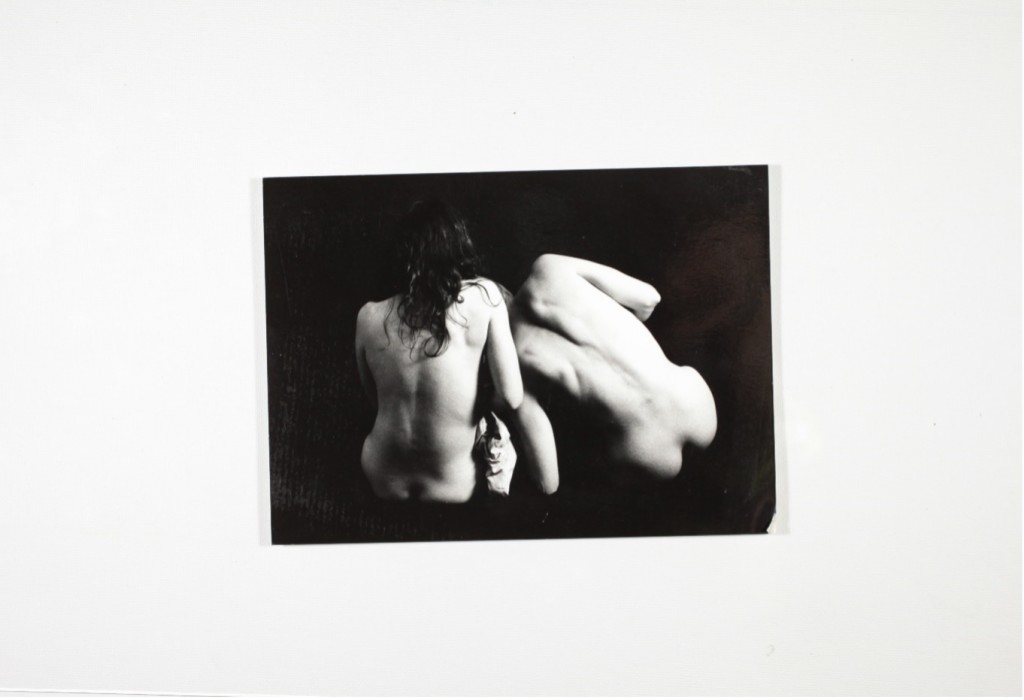

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

Christine Quoiraud:

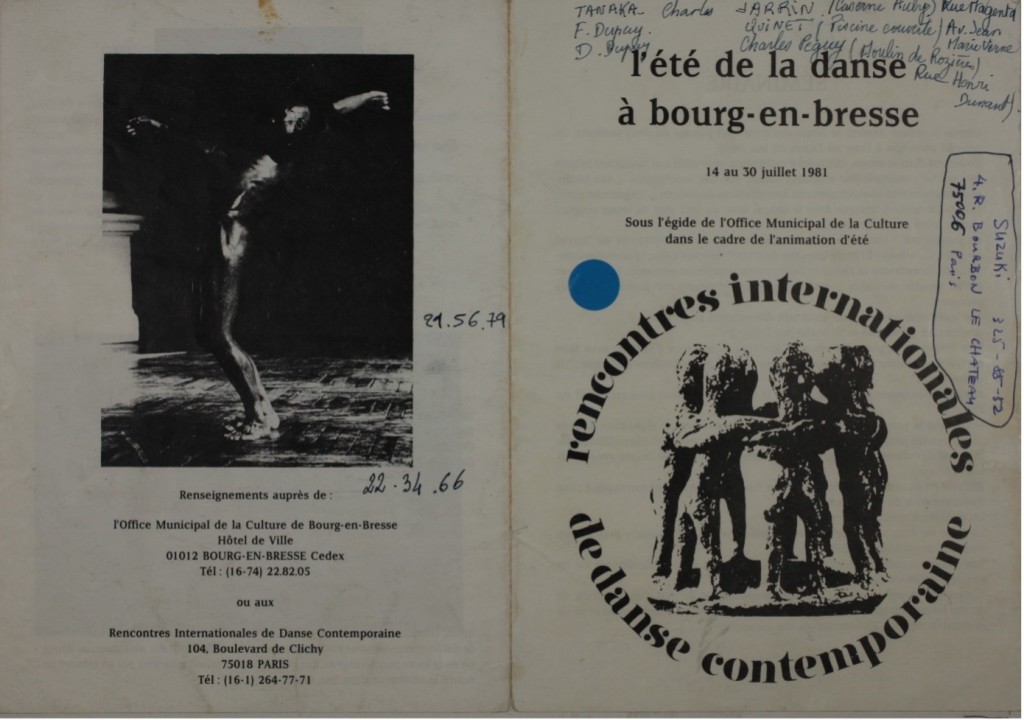

I met Min Tanaka in France, actually in Bordeaux, by chance. I was at that time dancing in a company whose style was based on the Cunningham technique. I was preparing a spectacle when someone came up with a small flyer with a photo of Tanaka Min advertising a workshop. It was the second year he came to France in 1980 or 81 in Paris, after a big presence in the Festival d’Automne in 1978. And that’s when he met Michel Foucault and Roger Caillois. Min Tanaka was giving a workshop in Bordeaux, so I left everything and went to his workshop. And as soon as I opened the door, I was captivated.

I remember it very well a sound-listening exercise was proposed: people were blindfolded and walked along a string laid on the floor. Min Tanaka produced sounds, clapping his hands or playing with paper. He moved around the room, changing heights and distances. We were supposed to point with the index finger in the direction of where the sound was coming from, and meanwhile you had to keep your balance, one foot against the other on the thread laid on the floor. It was a revelation, I was immediately totally convinced. Before that, I’d experienced several types of techniques in contemporary dance. At that time in France, a lot of foreigners were coming, many Americans, but also Asian people: I had met Yano and Lari Leong who already gave me a sense of what the state of mind of these parts of Asia was. But when I met Tanaka, that was it! I was totally won over. So, I immediately went to the next workshop he gave a month later in Bourg-en-Bresse. There were forty people. He was giving us the basics of Body Weather, the manipulations/stretching work, and a bit of work on sensations, and he offered us the opportunity to take part in a performance. So, he designed a kind of development for the performance, which was mostly improvised, with some elements given, with few instructions. It took place in a huge gymnasium. When the audience came in, we were seated in the audience and gradually we bent over slowly against our neighbor, we leaned on the public. Then moving down slowly towards the floor. And that impressed me immensely, actually. So, from that moment on, I quit my job, stopped everything I was doing. I bought a car to live in it. I started the Body Weather nomad laboratory. I travelled all over Europe. So, I was visiting all the Body Weather groups, which were being set up in Geneva, in Groningen, somewhere in Belgium, maybe it was Ghent, and in France, in Pau, in Paris. I’d travel from one group to the next, always sharing training and performances, mainly outdoors, in the streets, or anywhere in the city. Tanaka came every year from then on to give workshops mainly in Paris, or in Holland, or Belgium, and I joined all of them. Every year he would say to me: “Christine, why don’t you come to the intensive workshop in Tokyo?” I finally decided to go in 1985. Also, I came there with a visa valid only for that workshop, but I didn’t go back. I could not leave after what I’d been through. I stayed for over four years, almost five years. As far as I remember…

3. Maï-Juku V and the creation of the farm. Tokyo-Hachioji-Hakushu.

Presentation

In the minds of the PaaLabRes inquirers (Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff) the Body Weather farm project implied that a group of people had decided to live on a farm. Hence the idea that there was a beginning, which could be described in detail to grasp the origin of the approach. But the answers from the three artists demonstrate that this was not the case: the process of building the farm was very gradual and was inscribed in a constant back and forth travel between Tokyo and Hachioji (a suburb of Tokyo), then between Hachioji, Hakushu (the place of the farm) and Tokyo. This is one of the important aspects of the Body Weather idea: the body like the weather is constantly changing and not fixed anywhere. This concept means less the idea of migration or displacement, of travel, but rather of fluctuations produced by friction in a given environment.

We’re dealing here with three environments, one completely urban (Tokyo), one completely rural (Hakushu) and one somewhere in between (Hachioji, a suburb of Tokyo). The activities at the farm developed gradually in interaction with the local farmers.

Christine Quoiraud:

Before the beginning of the farm, the intensive workshop Maï-Juku V (1985) took place in Tokyo, in a suburb far from Tokyo, Hachioji with a dance studio. There were rice fields near the studio and a river, and we often went to work near the river. Or at one point we went to the mountains 30 minutes away. At the end of the intensive workshop, we moved to the farm for the final workshop of the two months period. We went into the water of the high waterfall, naked. This, and all that followed, was the key turning point. And Min was very proud to show us the farm. We all went there together. There was this workshop in the river and there was a fire after that, it was late October, it was freezing cold. We finished the intensive workshop there, on the farm. Then came the beginnings of the farm.

Andres Corchero didn’t arrive until February 1986 for the next intensive workshop, which only lasted a month that year.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

I don’t think that there was an “A-day”. I think it was really a long process of different events and different ways of working that led to finding a place and do on. So, I don’t know if there was a first day, but before I say that, I just want to point out perhaps, maybe just to say, that when I met Min in Athens, the part of his work that intrigued me the most was certainly the work that he invited us to do outside the studio, outside the theatre space or the studio space. And as Christine and Oguri have already said, Min was engaged in work that already involved weird places, situations and contexts, away from dance or any kind of formal art manifestation. It was a question of working outside so-called art spaces… Let me rephrase the question: what dance can be when experienced in many different contexts, when engaged with many different bodies, not only human bodies of course, not only one’s own body, but also the bodies of the non-humans? This question was Min’s major preoccupation in his work from that time onwards. That’s what I just want to point out, and actually for me, that element and that quest within the work that Min was doing inevitably led to creating a sort of place and network embedded outside the city, and outside formal artistic contexts.

Christine Quoiraud:

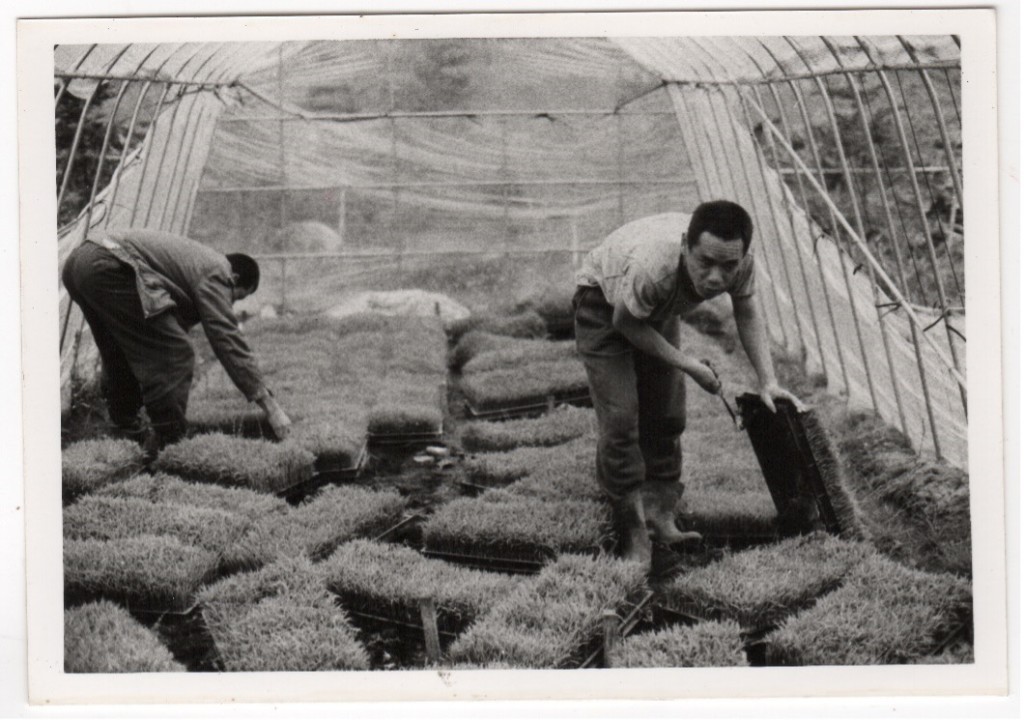

Like Katerina said, we didn’t start working on the farm straight away, it was part of a process. And, in my memory, we had to build and organize the farm before it became operational. We started by building several chicken houses. Oguri can talk about that much better than me. It’s only gradually, little by little that we got chickens and then started growing rice. In autumn and springtime, I remember you guys building the chicken houses. That’s when we had this wasp attack. Those wasps were in springtime, no? And planting the rice was more like June or something, May/June maybe?

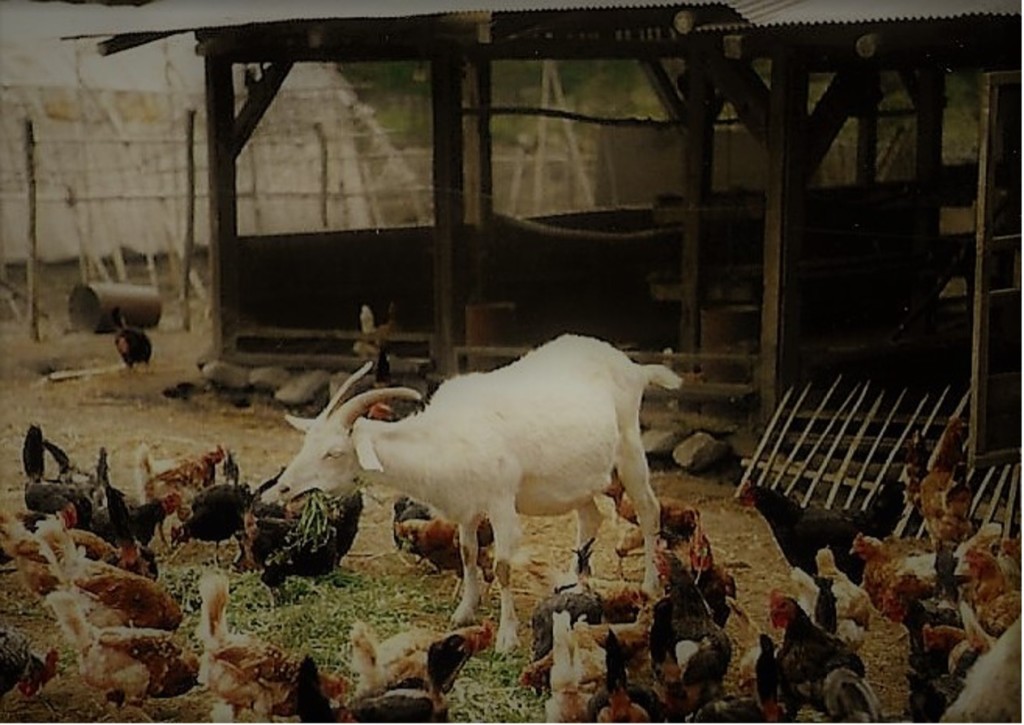

The farm in Hakushu, 1987

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

Oguri:

Shall I talk a little bit about the cycle? So hi, Oguri here again. Yes, farm was being prepared right before Maï-Juku V started… some friends were already working there at the time of Maï-Juku. I went at the farm with my motorcycle. And my first impression was that this land was so beautiful. Yes. It’s changed a lot now, but in the 1980s… Hakushu is about 100 km west of Tokyo. So, about 2 hours away with my motorcycle, experiencing a change of scenery, an evolving landscape, changing, changing, changing, so beautiful, beautiful river and gigantic rocks in various shapes, really almost like chaos. The last time I was there in 2017, it changed completely. Now, it’s not the same at all. But at that time… yes…

I know, a farm is not real nature. A farm is a work done by humans using nature. A farm is a human product in the ecosystem of nature, but there are still a lot of nature forms, mountains, and big rocks, and sometimes a typhoon producing a disaster that changes all human order, bringing back the nature. And it’s a quite high elevation area, around 800 meters high, it’s a cool air, water is constantly running by the house and rice field because of the slow open flat land. Yes. Hakushu lies at the foot of Mount Kaikomagatake in the 3000-meter-high mountains of the Southern Japanese Alps.

And as Christine said, in Hachioji, which is a suburb from Tokyo, that’s where already a big transition is happening, from the harbor of Tokyo to that city, Hachioji, where the Tokyo metropolis becomes Yamanashi prefecture and it’s a kind of transition before we go to Hakushu. And that transition is very interesting.

Christine Quoiraud’s personal collection

Min Tanaka and Kazue Kobata[3] are at that time running a small alternative performance space in Tokyo: Plan-B. This is like a first artist self-running alternative art space. It’s a tiny underground theater. So, every month, or every other month, at Plan B, Maï-Juku as a group presented a dance performance there. Myself I presented a solo performance there every month.

Yes, I will talk about that too: this has to do with something like transportation, transport: Tokyo, Hachioji, and Hakushu. A very interesting experience, transportation, moving, and activities in the three places: the farm, the workshops, and the performances.

Anyway, the farm is the place to return to after work at Hachioji, Plan-B in Tokyo, and national and international tours.

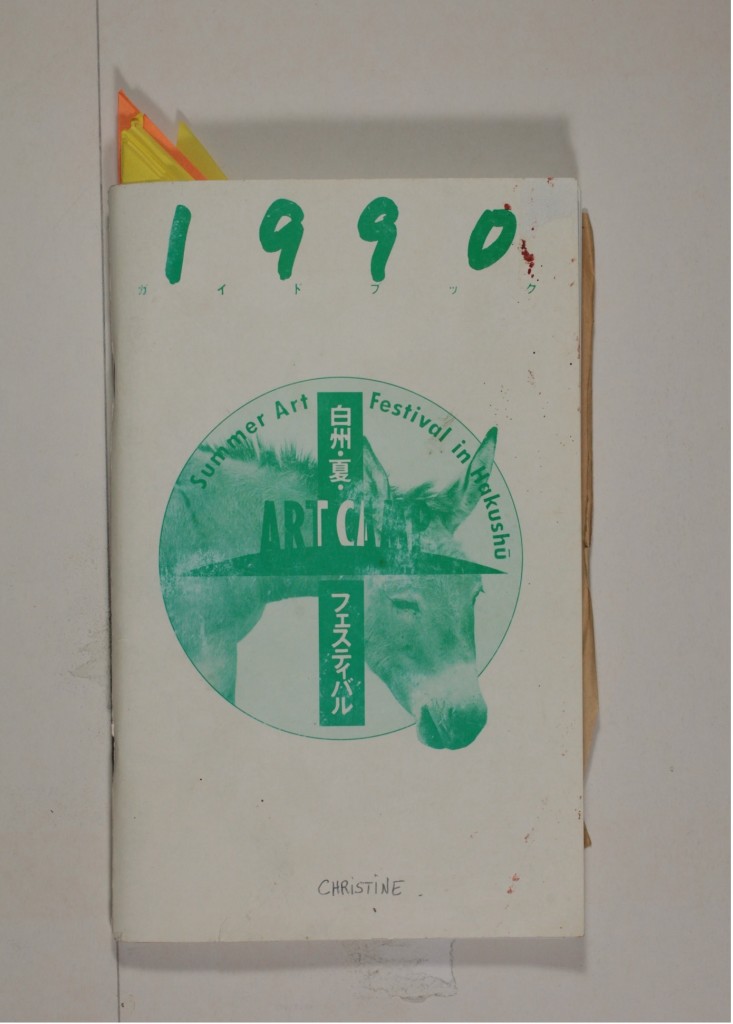

Living in Hakushu, the farm life, the traditional organic farming, experiencing the rhythms and cycles of this most human lifestyle. This connection of the human body to nature is necessary for Body Weather practice. We developed many things: the annual production of an arts festival, also with outdoor sculpture, traditional and contemporary performing arts, music, conferences, a symposium…

Photo by Frédérique Bua Valette, August 2019

Christine Quoiraud’s personal collection

Life on the farm necessitated a transition that was far from brutal. Our life is not shockingly changed. But, for me, it had a big impact on the life cycle: Tokyo, you have the night, you keep working in the night, you are in a theater, you have to start at 8 o’clock or whatever. But in that farmland, all farmers got to the bed at 7 o’clock. So, our cycle completely changed, working with a chicken, or irrigating the rice field. If you are late, you lose a day. Or feeding animals, they cannot wait. So, our cycle is completely changed. The night is completely dark, which is beautiful with the stars… So, that’s big impact, change. When I mention “life cycle”, it’s completely linked to most human lifestyle and the question of the human body. When we started working in Maï-Juku and Body Weather farm, we’re almost never alone, twenty-four hours a day. Always somebody is working with you, and every day you’re eating three meals together.

And I’m now jumping to the farm time: it’s a community group working together, but at the same time, you know, a very serious individual commitment is required at all times. Of course, just being there is a commitment, but in all the work both in the farm and the dance – I don’t say “the dance” but the workshop, the laboratory – self commitment was very strong. On the other hand, we’re not professional farmers. And I never think that I am a professional dancer either. This practice I’ve taken up, is it dance or performance? And as we are not like professional farmers, we learned from the farmers themselves on the job site, in the field. The idea that we’re not there to learn a technique is very important to us. It’s the same for Min or for the Maï-Juku Body Weather dance too. We don’t proceed from technique, but we’re very much like in a job site. I mean, it is not like a studio as a place preparing a performance elsewhere. So, farming was like this, and dance practice as well. It was a big transition: Hachioji had a dance studio floor, but in Hakushu at first, we didn’t have this kind of floor. Later, we built something like a stage, and we used a Kendo martial arts floor, to do floor work mainly in the land. So, farm and dance, neither had priority for the life in there.

Christine Quoiraud:

At the time of the 1985 workshop, Maï-Juku V, there was a lot of back and forth, going back to Tokyo, going to the farm and back to Tokyo, and in my memory, you were really one of the Japanese who often went with Min and Hisako, over there to the farm, to organize the venue of the group, and you are one of the witness of this beginning point, more than probably we, the foreigners, the non-Japanese. I’m sure you have memories about the discussions you had with the farmers, the neighbors… What do you remember of these talks when preparing the farm? From an administrative point of view, but also from the farm point of view, and also the necessity of organizing a program of what was going on in Tokyo and to Plan B, the performing space.

Photo Christine Quoiraud

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

Oguri:

Yes. These all three things happened simultaneously. Actually, I didn’t have much connection with the place in Hachioji because I lived more often on the farm side. Maybe, yes, Christine and Katerina, Frank and a few other people lived in Hachioji. They had rented a house there, so, your base was more in Hachioji…That’s a transition time. So, while living there, you were keeping a training in Hachioji. I remember that, during the Rite of Spring (or maybe not that one, another performance), we had rehearsal in the Hachioji studio. And then we went to the Ginza Season theater, a big theater, for a performance in homage to Hijikata. Yes, we built a set and rehearsed there too.

Christine Quoiraud:

That was much later. Hijikata passed away in January 1986. But at that time, there were lots of moves between Hachioji, Tokyo, Hakushu… It’s more a question of whether you have any memories of who decided, for example, to build the chicken houses?

Oguri:

Ah! OK! All the organizational side…. Min Tanaka had a big vision, I think. Why did we have these chicken, to what purpose? We didn’t need the chicken for the eggs, but for the shit, for the fertilizer. It was thanks to this fertilizer that we were able to successfully grow vegetables. Organic farming wasn’t so popular back then. We didn’t know about popular organic either. Yes, we didn’t use chemical fertilizers, we started like this. Use less chemicals, you know, weed killers or insecticides. That’s all we knew about organic farming. We didn’t even know about recycling, but recycling was already a tradition in Japanese life. It was nothing knew at that time, but organic was … how can you use it as in the case of traditional fabric. And besides, not much income.

It’s very interesting seeing that in the farm, Body Weather farm and Min Tanaka, we never owned the land. Instead, we just borrowed the land and the house. About agriculture in Japan in a village, of course all farmer families own their land. But most of the farmers are like Sunday farmers, they all have a job. They have a full-time job on the side. Farming is their second job, they have to keep the rice fields going, because as I said, rice is very essential to Japanese, rice is more than money, rice is like life, rice is like God. A bit like each of us, it grows, it develops. Many hours of intense work and a great deal of pressure during the harvest under the autumn sky. Rice grows and changes like a human being. Farmers must therefore continue to keep up rice fields. That’s an essential thing for each farmer. When the farmer gets old, children don’t want to take over being farmers. As a result, there are many fields, beside rice fields, as vegetable fields or mountains that are no longer tended due to lack of human power, so a lot of places are let to somebody to use. So, we got many places and fields that are like abandoned, and not in very good condition. So, we cut down the trees, got rid of the rocks, cleaned up the field and put it to good use. In many places, lots of farmers asked us to take care of this, as well as the house that goes with it. But farmers are always close to their money: after a few years, the field got intoo good conditions, “OK, give it back to us”. And you have to give it back. We were very kind to the farmers because we were learning a lot from them, and they let us use a lot of their land. So that was a very unique relationship between us and the village farmers.

Photo Christine Quoiraud

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

Katerina Bakatsaki:

In that respect, I also remember very strongly that there were times when we very often went to help other farmers – whether there was an agreement about it or not – and in fact, it was also a way of learning and knowing how to do things. I don’t know if Min pre-thought about it, but that’s how I have experienced it, while we were out there trying to survive with the minimal means, we had to at the same time try to figure out how to literally make things. What I mean by things, is of course the house, the objects, the lands, the animals also… How to live and work with these entities. Well, we lived there, we were also there helping the other farmers. Then, in fact, it’s not just the case in Japan, I know the same thing in Greece, the countryside and the farms are deserted, and young people are leaving. And on top of that, you have big corporations buying up farming land. That means that small farmers are losing their land and therefore the connection to their place, the connection to their land, the connection to the knowledge, and to their ways of living they’ve known. So, we were learning, but in this way our presence was also contributing in a very modest way to reviving also the life of the village, and thereby, in a way, literally restoring vitality to the farmers. And then, later on, came the festival that brought more activities in, and so on. I think that this was part of Min and Kazue’s vision, as a sort of conscious activism: OK, we went there to learn, but also to play a supporting role.

Christine Quoiraud:

And I think, how shall I put it, that it was pretty natural. Before going to Japan, I also lived in the countryside in France. It was very natural, when there was hay to cut, which was the case when I was a child, everybody came to help, and I think it’s really part of the life of rural community. Less so now because of machines, but at that time, up to the early 1980s it was still fairly universal…

In the early day of the Body Weather farm, there were not so many people living there, not that many… Like Oguri said, at the earliest, there has been the two-month intensive Maï-Juku V workshop. Then from the group of 40 people many returned to their own countries or personal lives. We remained to meet with just over ten people, half of them Japanese, the other half non-Japanese. I remember that there were about 16 people or something like that. Then, a small group of Spanish people came, and we remained a kind of settled group for quite a while, with other Japanese coming in from time to time, I don’t remember their names. And yes, we remained with the same number for quite some time, even a few years. But, a lot of foreigners, of non-Japanese, left… went to give classes and workshops in their respective countries like Frank in Holland, Tess in Denmark. They often left to teach in other parts of the world. I remember that. Katerina and I were there. Later, we left too… I mean, most of us remained there for a long time. I ended up leaving at one point, but it was mainly for personal reasons, like family in France, problems…

Katerina Bakatsaki:

I have to say that I only started teaching and even thinking about teaching after I came back to Europe after 1993. It wasn’t part of my vision at that time. Then in terms of knowing when we moved to the farm, I think Oguri you were there much earlier than Christine and I, for example. Is that so?

Oguri:

Yes. I lived may be two months or a month in Hachioji when Maï-Juku V started. And halfway through the Maï-Juku V intensive training, I started living on the farm. From then on, I lived there for five years. Living there, it is very hard. Nothing there was really prepared for living.

We used some rental house, a farmhouse, a deserted house. Nobody had lived in that house for many years. I remember that before the intensive training started, I went there, as I said, by motorcycle, with my tools, hammer, and a saw, like carpentry tools, to help build with two people from the village, Encho and Akaba San. They later became big supporters and mentors. The house had a big paper door, you know, shoji. Shoji door is made of paper. There were no heaters. I mean, later on, like after two years, everything was changed. But in the beginning, it was a very interesting experience [laughing], like the way people lived a hundred years ago, that kind of aura experience for one year. So, we were not but, in the beginning nothing was prepared. Later we prepared everything. We were not punished then. Yeah, basically that’s it.

Just one thing, gomme ne [Japanese for “sorry”]: what Christine said about watching things. Yes. This is very much like Japanese mentorship, you know, a mentor never talks, even in the case of Japanese cooking, traditional cooking. They never teach you. Yes, you have to steal, steal that technique… Then, there is always some gap too. So, you develop your own ability to do things. Yes. That’s what I wanted to add. And of course, watching is amazing, we were always watching. Watching is very important. After that, you can see the difference. That’s one thing I learned during my first year.

The first year, we knew nothing about how to grow things, except radishes. Radishes, you can get after hundred days. We really started from scratch at first. So living is also from scratch, but we lived from that land, and we got lot of support. All farmers giving us something, even agriculture equipment tools. That is, secondhand tools. And “You know, you guys, use this”. And at the same time, as Katerina said, we brought some vitality to the village. After a few months: “Oh, these guys are serious… OK, we better help them.” But it took at least a year to prove ourselves.

At the beginning, we all grew very, very long hair, it was for performance purposes. Min had some vision, all males and females would have very, very long hair, like wild horses on stage. So, everybody let their hair grow. For the Rite of Spring, we looked like hippies. All village people didn’t trust us or didn’t believe we were going to continue running the farm. That’s what changed after a period of two years, three years, year by year, our relationship with the community changed a lot. “All these guys working so hard, honest people, and who do these crazy dances.” Something touched their hearts. We organized that festival in the farmland, so we brought entertainment from other regions of Japan, or foreign countries, Japanese performers, singers, sculptors, and all these people brought more audience and activities there. We also helped them. “Actually these guys are not bad.” In fact, we were always invited in their homes. We had different languages: Greek, French, and Spanish. And with different skin colors. Of course, nowadays, the presence of non-Japanese, of foreigners has become a common occurrence in the Japanese countryside, but back then European, Americans, were rare and unusual. Yeah, it was a very unique experience for each of us. For the village people, I think it was a shocking impact at first. That’s what life was like there.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

In terms of who went to the farm and who stayed there, it changed constantly. Although you have to imagine, for example, that in the first year, I don’t remember for how long all the foreigners for different reasons, good or bad, were still keeping houses in Tokyo, in the suburb of Tokyo, in Hachioji. While some people, like Oguri, had already moved to the farm. So, we’d go to the farm, us foreigners – correct me if I am wrong, Oguri and Christine – while still keeping our accommodations in Tokyo, because we all also had to work to earn a living, because there were costs involved for us for transport tickets, for business, and so on. For different reasons, we felt it was necessary to keep somehow a foothold in Hachioji, and work to earn money in Tokyo. That’s what we did. However, there was no money involved in our commitment to the farm or to the dance practice, to the practices we did there. That’s why we kept our lodgings and our jobs, and the studio in Hachioji, and we would go to the farm either when hands were needed, or when we would have to rehearse, to prepare for a group performance at Plan B.

So, the constellation of people at the farm changed a lot, absolutely all the time. There was a core group that would be at the farm on a more regular basis, and then we’d come to do farm work, for rehearsals and dance practice, and then we’d go back to Hachioji. Now, you have to imagine that – and this brings me to your question –when we were there, then the work had to be done, because things needed to be built, the chicken house, the fence needed to be corrected, or some chicken needed to be slaughtered, just to name a few things… We did the farm work and the maintenance work for the place, which were also considered part of the training. I mean, engaging with material, engaging with the timing of another thing, another material, another form of life, was considered as part of the training as well. For example, more concretely: how to weed the wild grass, you have to bend down to the ground, you have to work on the ground, it’s small, it’s small, and we were not using electrical tools, we only use all types of tools that were almost extension of one’s body. So, a massive part of the training consisted of finding the best ways to use the body to be efficient in the work. The understanding of how to exert force, in which direction you are going to gear the movement, so, how to use your wrist to grab the grass in a way that you can pull it out with its root, so that it doesn’t break. And so on, and so on. So, that was part of the training.

Now, indeed, because we had to rehearse as well, there were hours set aside for artistic training. So, we had to wake up early in the morning, feed the animals, do the urgent farm work, which was already a form of training, and then have a very quick breakfast. And then the rest of the morning was devoted to rehearsals, then lunch again, and then farm work again. It was happening in a way that I wouldn’t call “organic”, but all the different needs, all the different concerns needed to be taken care of, to be attended to. This is how the day was being packed. The cooking was done, as I recall, on a rotating basis. I remember, me not being able to boil an egg, having then to prepare dinner for 15 people. The panic!!

Christine Quoiraud:

And sometimes we fasted to prepare for performances.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

Oh sure, oh yeah! But [laugh]…

But attending to things, attending to needs, whether it was a performance, whether it was a personal need, was as much a matter for the people who were present at that time. Attending to food, attending to the maintenance of the house and of the place, attending to the life, to the social life in the village, because that was also a big part of the activities. I can still remember spending a full day doing different kinds of work, and then ending partying, I mean, eating and drinking at Akaba’s house, or at Encho’s house… until early in the morning (Akaba San and Encho were two of the farmers who supported us). And then…

Christine Quoiraud:

We were young!!!

When I first arrived in the summer of 1985, there was that studio space in Hachioji in a suburb of Tokyo. And there were already animals around the building like chickens and a pig. And always a dog or two, or a cat or two, yes, and we lived with that presence. They were really small shacks near the building for the animals. It was in the suburbs, but it was still the city. There were no fields as such. There was no farm, just a dance studio. Nearby, there were rice fields, but not so many, and a river. So, the main activity was in the studio. Already Plan B existed in Tokyo. To go to Plan B took like – I forgot – but maybe two hours by train. I’m not sure but it was something like that. So, we often travelled from the studio to the city center.

And before that, Min Tanaka, when he came to Europe, often took us to work outside in parks, anywhere. And when we were still in Hachioji, during the intensive workshop (1985), he took us to the mountains for a week. That means that we were also dealing with wildlife in the mountains. And then, at the end of 1985, beginning of 1986, we started the farm. There were a lot of travelling by truck or by car, from Hachioji to the farm. And then, gradually, a team of dancers lived at the farm. Others continued to live in Hachioji. They kept jobs in Tokyo to survive. And then sometimes we would all gather at the farm to work, to carry out a major work, or to rehearse for performances. And then, sometimes we would go on tour in Japan. So, at the beginning, the core place of the activity was in Hachioji, and very soon after its opening (at the end of 1985), the farm became the main place.

I would like to add something about what you both said. About language, when I met Tanaka Min in France, he practically spoke no English at all. He used a translator, so he was at that time surrounded by a bunch of young Japanese, who were studying with Gilles Deleuze in Paris, and were translating for him. At that time Kazue Kobata was always travelling with him, and she was also translating in English, and she managed to introduce Tanaka to Michel Foucault, and, if I remember correctly, to Roger Caillois. And Min really talked a lot with both of them and was very impressed thanks to Kazue’s English. And then, around this time, I think in 1981, Min went to New York, thanks to Kazue. There he met Susan Sontag and musicians like Derek Bayley, Milford Graves, and so on. And, from then on, Min started to study English. Gradually, when he returned to Europe, he could use anatomic terms to explain manipulations, but he still always had a translator. And when we get to Maï-Juku V, I remember it very well, Min spoke much more in English, he asked the Japanese to learn a bit of English, and also encouraged the foreigners, non-Japanese, to study a bit of Japanese. In reality, and still today, there’s this kind of broken English between us.

Milford Graves and Min Tanaka at the Body Weather Farm. Video by Eric Sandrin.

4. Body Weather, Farming and Dancing

Presentation

Body Weather was based on the idea of perpetual change in the body and the weather. This raises questions about different ways of looking at farm work and artistic production work, the relationship between everyday life, the environment and dance work in its training and performance dimensions. Participation in the Body Weather farm involved a very intense commitment to all aspects of farm work and dance. But this commitment remained based on individual confidence in the philosophy of the project, and not on blind adherence to a closed community.

Oguri:

I want to explain a little of the history on a larger time scale. The Body Weather Laboratory I think started around the 1980s and lasted until maybe a few years ago, that means about a forty-year history. And I was there five years, so that’s what I am talking about, my experience over five years. I left in 1990. During that period there were many changes, and before I was there it was another time too. And about Shintaï Kissho, “身体気象”, “Body Weather”, that’s kind of a method of this movement: the body is not a fixed entity itself – not stable, fixed territory. It changes perpetually like the weather. Not like just one season; weather is constantly changing at any moment.

Christine Quoiraud:

I have a question for Oguri again: do you think that Tanaka had heard then of Masanobu Fukuoka?[4] Because I think it was in the 1970s that he left his job as an engineer and started to do organic farming, creating a commune. I think he was pretty well known then for the way he gathered volunteers to work on his farm and he had a commune that changed all the time, young people coming to him to learn and help. They lived there in a very sober way. And that reminds me a lot of what we went through in the beginning of the farm. For example, there was a group, forming the main group, mostly Japanese, living on the farm, and foreigners who came from time to time to do some special type of work with the neighbors or without the neighbors, and then also throughout the year there were volunteers coming to help from different parts of Japan. So, I was wondering if Min had heard of Fukuoka? I don’t remember hearing him talk about this guy but… may be…

Oguri:

I’ve never heard Fukuoka’s name from Min Tanaka’s voice. He never did mention him. I’m sure he knew but he didn’t mention it, but I think that’s very much Min.

Just one thing, I was about to forget about that. Going back to that first time when I was working in the farm, I was very impressed by the land. At the same time, on the farm, labor is not done for someone, labor is for yourself. Because people in urban environments depend on their customers, or their boss… But there, on the farm, as I said, there was a form of commitment and responsibility, but the whole work was for yourself. That was a very strong kind of our commitment and, you know, and that was the purpose for being there. Including the dance too. That’s what the dance method was all about. It was a very simple world and nothing special. Of course, you had to make your own decisions and, as I said, we are not professionals at that time. We have to find things out on our own – like some answers, because all the neighbor farmers were like mentors too. I remember that. And let me talk about land also… I know I had very different perspectives from Fukuoka. Like: what’s special about a region, regionality. What’s particular in that area or region, in that place… How to say? There are traditional ritual or celebration dances. Celebrations or some rituals, or kagura,[5] or dances there – we learned a lot about how to cultivate the land and how we think about the origin of dance. Because this type of method, Body Weather, is not a dance technique as such. Min Tanaka, he never teaches us how to dance, no. In other words, our practice is not a study of how to dance or a practice confined to the studio. Our training is very much oriented towards sensitivity work. And… the class is very open. I mean, our dance is very open for any kind of skill.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

As far as I know, the term Body Weather was borrowed – not borrowed but taken – from Seigow Matsuoka.[6] But am I right to think so? I am not sure. I mention this because when Min was working, traveling, exploring, with Kazue Kobata, he was also a lot involved in artistic and thought movements taking place at the time. The stimuli that gave rise to the work that emerged, to everything that he did, were of a theoretical as well as philosophical nature, and had also a very strong connection to movements of thought already existing in Japan, the United States and Europe. So, I just want to bring that in… Of course, I don’t know. I am not sure if Min has explicitly spoken about all this. I do know that Kazue Kobata did, and I’ve had conversations with her about it, about all the different movements of thoughts that were enlarging our approaches and encouraging Min to continue with the work he was doing. Not only Min, but also all the artists that he was working with. Because he wasn’t a solitary genius. I think we all had that kind of experience! There was always the presence of an extended community.

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

5. Commons and Body Weather

Presentation

Commons, what we call in French « communs« , can be defined as an articulation between resources that exist within a community, and rules concerning the way in which that community operates with regard to these resources. In the Body Weather experience, we can see that there are a lot of resources linked to the farm and to the dance practice, to Plan B and to all the spaces around the farm. How these aspects of common life were organized, how did the community function in relation to different interactive practices taking place in different spaces, environments, and with living creatures and objects? It’s about the conjunction of experiences, the existence of a community with little in common between its members but a commitment, autonomy and responsibility, taking initiatives in a non-formal structure, perpetual movement and evolution.

Christine Quoiraud:

Well, there’s not ONE answer to the questions about the commons. If there is an answer, it has to do with the passage of time. When I first arrive in 1985, things were different. The farm didn’t exist yet. And then the farm started. Then the farm continued. We started by building the chicken house and growing rice, and it was a gradual change. So, there are several answers, many answers.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

Allow me to use the word “community” not in the sense of a closed church, but as a network of forces, of people, of contexts, that always been central to Min Tanaka’s engagement. A bigger community of people, of artists, who had the same questions and the same concerns as he did. That’s one thing. And another thing I’d like to say, concerning that question of community: you are there because you’ve chosen to be, and you better have the guts and the commitment, for yourself, to fully engage. We’re not there to do it for you. And at the same time there was no pre-agreed reason for why we were there, there was no common belief. We are all here because each one of us had totally different motivations, and different interests, and different types of investment. Personally, I found that precious, I would not have stayed otherwise.

And also, I speak for myself, it was always important to feel things out and also to register with myself. That’s what was interesting because, you know, I was young. Intuitively I could understand things and give them a place, also listen to my experience – not the dance experience but the life experience – I’d acquired from the place I came from. And also the ways of being in community, the ways of doing things together, the ways of understanding and sharing work, where we lived together with others.

But, for me, it was also important to feel that I could actually betray that sense of commitment, even if only with myself. Why do I say that, because it gave me the security of knowing that I wasn’t in a sect. That said, I also want to say that it was fascinating at the same time how all of us, each one of us, were there out of our own different motivation, and still we had all made the commitment to be there together. And also doing things together, without there being any agreement on what that should be. Of course, there was the training, there was the necessity to grow as artists and eventually as people. There was a trust in witnessing the work and its potential outcome. It was not about developing a method, but in the way questions were posed: about dance, about movements, about land and nature, and about non-nature. So, these questions were present in all forms of production, in any kind of work activities, that had to be carried out, whether it was cutting the grass, whether it was learning from other farmers who have been there for generations. When they tried to figure out who we were, they wondered if that was “making mistakes”. But the commitment was to actually do that together. So, in terms of commitment, I mean, that has been always for me very interesting, very fascinating, very exciting. I always had to commit myself to something other than just myself. It’s something that exist among farmers, they know that you have to feed the animals, you are not on a vacation, you have to be there.

There’s no division between leisure time and work time, you have to be there, available, and your rhythm and your needs, your body are available for the service of something else, of the animals, of the plants, of the seasons, of the water that follows its course or stops flowing, etc., etc., etc. So, that sense of: “OK, I’m an individual, I’m here for myself, and I’m responsible for my actions, I’m autonomous”, and yet there’s always this call to actually relate and commit to something else that isn’t myself. And it’s not necessarily linked to that community as such, it’s always bigger than that. It’s the other humans, as being together, but it’s also the animals, the plants, the cultivation, and so on. The tools that we use. Yes, there are a lot of nuances to this notion of commitment.

Christine Quoiraud:

I think we learned a lot by watching… by observing, which is also a way of understanding farm work, like, I remember, when we went to help Encho (one of the farmers, a neighbor) in the rice field. He showed us how to cut the rice and hang it on a pole. It was a situation of having to observe the action, in order to be able to do it ourselves. Or when he showed us how to use a tool to turn over the wooden logs on which shitake mushrooms grow, we watched his gestures so we could imitate them – not imitate them exactly – it was a question of grasping, of embodying the gesture of the one who knows how to do it.

And I remember myself trying to follow the M.B. training (« Mind and Body training », a very dynamic training as part of Body Weather),[7] I had to watch the bodies of the guys in front, of Min when he was correcting a little or showing different rhythms or other things. And when he was directing the preparation of the performances, it was the same. I’d listen, I’d watch his body rather than listen to what he was saying, his explanations which remained a bit surrealist for me. But for me, his body was not at all surrealist, I could grasp a lot of things. And by the way, Oguri, in my memory, before Maï-Juku V, there were a few solo performances at Plan B. But from Maï-Juku V onwards, Min started choreographing to encourage us – I think I was kind of the first one of the foreigners of that time to present a performance. So, my composition was first. Everyone laughed… So, I asked Min to choreograph my next solo. It was early January 1986, shortly before Hijikata’s death. Afterwards, Min encouraged everybody to do a performance once a month, which the three of us did as much as we could. This was in parallel with the collective work of the group, or the work directed by Min Tanaka. Each of us had the opportunity to develop our own research and test it in front of an audience at Plan B, which was an amazing privilege, an amazing way of learning… and also an extraordinary proof of trust. Voilà.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

In terms of the possibility of proposing initiatives, I don’t recall having the need to do so. However, I also don’t have the impression that I’m someone who passively follows the course of things, because I could have my own ways of engaging with things, like for example I could have my own motorbike and, at given times, I could move away from the farm and come back whenever I thought it was necessary. So, I, personally did not feel the need to initiate concrete things. And I guess, I am not also the type of person to do that, but at the same time I never felt I didn’t have the space for myself and act on my own, to make decisions independently and autonomously.

I think if Min had not given the trigger, suggesting: “Why don’t you do…” I’m not sure I would have done anything. Actually, Min somehow encouraged me, and yet, in this context, there was plenty of space to do our work, to do whatever it felt necessary to do. Given that there was a space also, Plan B was there, available to us.

Christine Quoiraud:

I think we initiated small things. Oguri, maybe you remember, when we started working together, we were in charge of the communication, how to say, designing the Plan B calendar, and at one point, I was translating into English – I had to work with Oguri, because I had no idea of Japanese. These are small things, but they added a stone to the edifice, to the main project. And as far as I am concerned, I managed to take a lot of initiative on my own, in the same way that Katerina could take a motorbike to escape. So, I was also able to take small initiatives to resource myself, so that I could then come back to taking part in the group. And it was because I was not Japanese, sometimes I really needed to do that, and it was by returning to my own language, to the French language, that I was able to realize this. I created a French language poesy club in Tokyo

Katerina Bakatsaki:

I think there were different places. It’s good to look at them from different angles. At the beginning there was a location in Hachioji, which was the dance studio. Then there was the farm, something completely different, a place with its intrinsic structure, with all its complexity and its improvisational character. We have also a seminal place, Plan B, a performance space. And all sorts of other places where performance would take place that were either theaters or outdoor places, within Japan or elsewhere. Then there were also all the places we had to go to sell and deal with the products of the farm, and I think that was part of our lives, of our practices as well.

If I try to define the commons in terms of locations, there were a) seminal places, b) important locations and c) places where a particular activity took place. Of course, there were other places as well, and, later on, came another house more to the south, close to the sea.Because the Body Weather farm was in the mountains. But, I mean, the life of the group changed in relation to these different places. I hope that this makes sense. So, again I repeat, it was Hachioji, the studio, and of course the houses around it, this particular space, a kind of small village situation on the outskirts of Tokyo. And then, you have the farm, you have Plan B in Tokyo, the theater space, and you have these other spaces where performances took place. Then, in my perception, there were all the big activities initiated by Min, so most of the important performances, the tours, and we were invited to participate. We were never obliged, but we were invited to take part.

There were also the moves – Oguri and Christine correct me if I am wrong – the big moves to the farm. I mean, these big migratory moves were initiated by Min, and maybe also in collaboration with Kazue Kobata and with other people who belonged to the artistic scene of Tokyo at that time. But these big moves were initiated by Min, and we were invited to participate. Plan B as a space was already in existence, I think, at least when I arrived. So, we have these places that exist, and we have some sort of structure that moves around that it is initiated and triggered by Min, Kobata, and the people who work closely with him. And then, within these bigger main locations and structures, we’re invited to participate by taking our own initiatives and to create our own work. That’s how I see it, that’s how I can make sense out of it, because a lot of it was left to our own initiative, I mean it was growing as we went along and according to needs.

That’s how I experienced the development of the different activities. The animals arrived. The rice fields had to be taken care of. Because that’s what was happening on the farm, we had to take care of it. In a way, there was an aspect of organicity, but at the same time there were many things that were already there, or that existed on Min’s initiative. I mean, the big performances, big theaters, were initiated by Min, or by other artists who had invited Min to participate or to choreograph, and then he would also invite Maï-Juku group to participate. So, some of these commons were determined as and when necessary, by the need to do something at a given moment. But each one of us, in different ways, initiated, supported, followed or redirected what was happening. But there was also a bigger structure above all that – I call it structure, but it was a very fragile structure, a non-formal structure: Min had his vision of things, and he was going on, he was moving on. Who wanted to join, fine, who did not, bye-bye, something like that. And yet, within that, there was a lot of space for us and a lot of invitations from Min’s side for us to take our own initiatives, to develop our own creativity, to have our own connections to the different places, to be there and understand and feel what needed to be done.

Oguri:

So, as I said before, the movement of Body Weather history is also constantly changing, as Christine explained. Katerina said it too. “If there’s something that we need, [chanting] we———– are going to do it.” Commons, the commons are not permanently fixed: the farm, the dance company, and Plan B. I was completely involved in all three activities, for me it’s the same, there’s no separation. There was the nojo’s [farmers] community. The community of who worked the land. People who weren’t involved in the performances, other people included in performances, but not in those of Plan B.[8] There were different ways of looking at these “commons”, a little more flexible, or expending and moving to. On the subject of Maï-Juku, moving from Hachioji to the farm was a big transition. Since the beginning of Body Weather, not as a parameter but as, let’s say, the essence of Body Weather, there was no question of staying solely at Hachioji, in this dance studio. It was necessary to move the activities to the farmland, to the rural world – I don’t say “nature”, just “farmland”, or environmental place. It’s just as Min Tanaka had done when he started dancing, first on the street, then in a theater. And now again, it was question of dancing in a specific site or outdoors. He never fixed the stage, but integrated into new places, moving to one another. So, I hope you understand, Maï-Juku is not a dance company – yes, in a sense it is – but it’s not a dance company fixed once and for all, with a choreographer and contracted dancers, who get paid for their performances. Not at all like that, yes… And at the same time, it’s another context that depends on individuals – I think I said something about a strong commitment on the part of individuals – it is very much organized, but it’s also very much an individual thing. In fact, now, Christine, Katerina, and I, we’ve been working completely separately and developed very different dances. So, we weren’t there to assimilate Min Tanaka’s choreography or to acquire a technique, Min Tanaka’s dance technique. This community is not like this. The commons are determined by the individuals within the commons. To come back to individualities – is it really linked to the commons? (I’m wondering myself) – obviously, financially, it hasn’t been easy for anyone. Because I was there for five years, from the moment we started working on the farm. We started by learning from the farmers how to do it. Yeah, none of us were experts at it at first, so, we were learning that. So, farm work didn’t pay as such. No, maybe at that time, dancing, big projects, brought a bit of money or commercial work, movies.[9] So, yes, many things were happening at the same time.

The farm started I think in 1986. All village people didn’t trust us or didn’t believe we were going to continue running the farm. That’s what changed after a period of two years, three years, year by year, our relationship with the community have changed a lot. All these guys working so hard, honest people, and who do these crazy dances. Something touched their hearts: that first year, Min, Kobata San, and other people organized a festival, the Art Festival, a pioneer project in Japan, outdoor. Something that never happened in Tokyo metropolis. But in this more marginal place, in the farmland, outdoor, a performing art event: sculpture, and music and performance. We brought many entertainments from other regions of Japan, or foreign countries, Japanese performers, singers, sculptors, and all these people bring in more audience and activities there. That was very much like a pioneer project in the 1980’s, now it’s getting more common place. It was another activity form of Body Weather activity and beyond, and we were all involved for this at the farm: farming, studying, driving the dance, and organizing, producing events. We were getting more accepted by the community. In fact, we were always invited in their homes. Of course, nowadays, the presence of non-Japanese, of foreigners has become a common occurrence in the Japanese countryside, but back then European, Americans, were rare, it’s unusual in that time, yeah, it was very unique experience for each of us.

Oh yeah, another thing, this is a bit symbolic about rice: rice is a very essential matter we plant, especially for the Japanese, I already said that. There are so many names given to one grain of rice, from the rice growing to the rice coming to my mouth, the name changes. It’s like these different names given to water: ice, water, snow, all transformations giving rise to different names. So many names are transformed each time in relation to other ways of being. That’s how the commons can be seen in the context of Body Weather. But I’ve learned from that tradition in the field – OK, all right, maybe I’m probably creating chaos – OK, ask me some specific questions! [laugh]

Christine Quoiraud:

I can add something which maybe extend somewhat or is connected to what Oguri just said: I remember that when we started the farm, there were no animals. The main focus was really on rice, getting the rice crop going, and then, gradually, we built the chicken house, and suddenly there were thousands of chickens. It wasn’t just Min who decided on the development of the farm, I think Hisako played a big part in these kinds of impulses. Suddenly we had goats and donkeys. And I remember that, when I left Japan, Tanaka Min offered to entrust me with cows. He wanted, me to take charge of the cows. I said: “No, thank you!”. But it was a way to establishing a relationship. We spoke about the place. This was how the original group had to adapt. These animals had to be taken care of, they were part of the environment. At first, they weren’t present, and then a little bit present, and more and more present. And so, the rice was like a must, because in Japan it’s everywhere, as far as I know… But the animals, it seems to me, were very important for Min and Hisako. The animals were present also for their shit as a fertilizer, but also to earn money, because we were selling the eggs. I’m thinking clearly about the animals and their sounds and their smells and their pee.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

I just like to try and clarify this notion of commons and of community. Because from many of you, you hear it said – and it’s also for me, wonderful to hear it – again and again, again, that there is a community in existence. But in the context of Body Weather, there was nothing in common between its members, and this is what gave the project its particular strength. Of course, there’s dancing, there is a need to dance and to explore dance, to explore how to understand dancing in life, how to relate, how to exist with each other, how to exist with things, with objects, with plants, with tools, with money, with no money, how to exist within other communities that also exist with us, while we are also not exactly sure whether or not we form a community. We just didn’t know. At least I didn’t know. I don’t think that we ever felt that there was anything we could designate as part of a common order.

There was a shared desire to be there, but each one of us had our own particular needs, expectations, and projections, and so forth. And also, their own ways of engaging with all this complexity, or chaos in other words, not chaos in terms of whatever, but chaos in terms of unpredictability. Everything relate, we are related. There are principles that are laid and guide us and stay with us, like the rice, like putting ourselves in relation, like questioning ourselves, how not just be in relation, but questioning how to do it, that is to do what we don’t know. Also questioning the morals, the ethics, and the politics of all that. Nobody decided: “OK, this is how we are going to do it”. We thought about it, we were figuring it out. And yet, and yet, and yet, there were bigger schemes that were constantly in motion, by which I mean that all notions were constantly situated in particular contexts. There was always the presence of all kinds of dancers, of bodies, as micro-communities. The community without something in common, that was very radical, it still is, at least in my mind, and that’s why this whole bunch of people wasn’t a sect, there’s no promise land, no obligations. We were there because we’d realize that “OK, I can do this, I can relate, I can respond to what needs to be done, I can…”

Christine Quoiraud:

Just one more thing. As far as I remember, the shape of the group and the activity developed on their own, but when we were on tour, when we travelled to France for performances, I remember that there were a lot of differences between what was relevant to the Japanese world and to the European universe. Min often talked about the tradition, tradition in Japan… And when he was in Paris at the time, he was somewhat critical of the style of democracy in use in France. I just remember one of Min Tanaka’s “remarks” when we presented the Rite of Spring. Nario Goda,[10] a dance critic, was with us and he fell ill. He was in hospital for a while, and Goda San, Mister Goda was very excited: “Oh, I am sick, I’m going to stay in Paris, I want to stay in Paris, I love Paris, I love France, there’s lots of good food, good wine …” And Min Tanaka said to him: “No! You shouldn’t stay in France, it’s too soft, the mind is too soft, the mind is too mild”. It spoke to me a lot, then, it was like: “In Japan, we can have this strong energy, this strong capacity to work. We don’t stop, we don’t give up,” like the Cossacks – an image that comes from me indeed – but that’s how I felt a bit at the time. You’d never get tired. You could continue even if you were tired, yes, absolutely… So I suppose Min was also wondering what it’s about to be a group, how a group could behave, how life with others could be envisaged. How is it to live with several people, and with an ever-fluctuating number of participants. During the first year, there were a lot of people on the farm, and then in the middle of the winter, it shrunk. The size of the group varied constantly. There was, I think, something akin to a non-adhesion to capitalism, in the way we were confronted with the economy. But on the other hand, to my feeling, there was a strong tendency to turn to tradition. And as a result, there was this tension between tradition and a certain willingness to invent something new. And probably, other influences, I don’t know, but I think I can feel or imagine something more open, somehow, – I would not dare to use the word – a certain anarchy, but…

Oguri:

Just I want to say this: as we are related to the land, it is also the case with dance. Dance is mobility, it can take place anywhere. With just the body you can present dance and it’s a one-time thing. And we don’t own our dance either. So, I think, it’s a very effective method. What I mean is that if we consider this notion of communs or of the commons, it’s kind of the essence of Body Weather: of not owning the land, of not owning the dance. It’s not about ownership.

So, that make sense now, that the dance and the land are always rented. We borrow the land and the dance as well. But during the pandemic, it is the first thing that becomes impossible, it limits the dance so much, that we can’t do anything. Yes, I am sorry to remind you of that. I’ve always thought that dance was the strongest media, you don’t need to carry instruments, you can go any place, just with your body. But during the pandemic, it was so difficult. I’ll stop here. OK, thanks.

Katerina Bakatsaki:

And yet, we as dancers we’re always moving. I mean, it was always another fascinating for me the way while working the life of the group was growing, that there’s a sense of mobility, of sudden shifts, changes of direction, mutations, movement. And yet there’s the question of not owning land, and yet there’s the question of working the land, of relating to the land. Getting your working hands dirty…

Oguri:

… Yeah, rooting, finding you roots…

Katerina Bakatsaki:

… finding your roots, working the land, I mean, creating a relationship with the land, as you say, with the rice field. Understanding also with the body, what it needs, its timing and being able to accommodate and support it, to be at its service, the same thing with the animals, the same thing between each other, the same thing with the music, the same thing with performances, wherever we are sharing the space with others, whether they are human bodies, or objects, etc. I think that was this notion of working the land: finding your roots, without owning. And this, for me, now I am recalling it, also with hearing your words, and “Ooooooooh!” [laughs], it’s really inspiring, time and again. And I think that was in terms of this notion of the commons: you know, things are moving, shifting, places are changing, we are embracing what needs to be done, etc. And so, there’s a constant move, and yet we need to get the actual relationships working with the village, with the villagers, with the rice, with animals, with the land, with each other, and so on. So, we are not owning land and yet we are working the land, again and again.

Oguri:

That was our Body Weather community. But you know, sometimes I feel that’s the big reason why I left the Body Weather Farm, was because it was at the same time a very old-style community. These farmers were very conservative too! Yes. But that was a kind of challenge for Min working there. I am not putting it, how to say, that he is not a great man and a fair person either, but I think at that time… OK I shut up now.

Photo Christine Quoiraud

Archive Christine Quoiraud, CND Mediatheque

6. Choreography, Improvisation, Images

Presentation

Was Min Tanaka a choreographer? It seems that he wasn’t in the strict sense of the term, but he was nevertheless an initiator of performances and stage director of dance. This meant that there were hierarchies in the artistic value of different forms of choreographies. Given these circumstances, what happened in reality during the preparatory sessions to performances? How much improvisation went into the performances? What was the place of technique, if it made sense?

The presence of images was an important element that enabled different pieces to formally emerge.

Oguri:

First of all, at least in my memory, in the 1980s, Min Tanaka never put his name on programs as a choreographer, such as “composed by Min Tanaka”[11] in a group performance, I remember it well. Composition implied a very strong framework. And choreography what task is it? It changed over time – I am just talking about this1985/86 period – it is a task, a movement or choreography proposed as a task. The task of jumping in the air, a task like jumping up one hundred times, and body straight. That’s an example. But composition is like a very clear road map, whereas usually we never repeat the same performance again. Even in the same series of performances. The second day, in the same series, a lot of changes take place, even this composition is slightly subject to changes. The next season, the performance resembles the original model, but still with some little differences. So, performances never stayed the same, at that time.

Later on, especially when we were living on the farm, then many productions, rehearsals took place on the farm. Indoor, in a studio – it’s not really a dance studio, it was in the house, we had a bigger room there, upstairs. So, rehearsals took place there or in the field, where we built a stage to rehearse. Again, for the performances it would create different situations. Sometimes we are doing the performance in the small studio, or at other time we’d present in a big theater the study pieces we’d created in the small studio. Processes were different. Usually, we worked out composition. And since we were living together, composition could be explained in a more abstract language… But very much related to each individual body. Body including spirit too, yeah, not like considering if someone had flexibility or if someone moved well, it wasn’t that important. And there was a lot of improvisation involved. Min demanded so much responsibility from each performer. Min Tanaka didn’t say how to move, he didn’t determine the form of the movement to choreograph. Later on, when we had gained a lot of experiences of dance in the farm, in outdoors, I remember a composition – very, very simple: just being there, assuming a presence. But each time, after rehearsals, he’d tell us clearly what he noted for each dancer individually. Everything he observes gives rise to very clear comments pointing to change things, to make the performance better, yes, without ever giving a goal to achieve. That’s what I remember about working in those days. Thank you.[12]

Christine Quoiraud:

We worked a lot with images, and these images came from Tanaka Min’s experience with Hijikata who choreographed a solo for Min. He used the images maybe from that moment on, the years when he was working under Hijikata’s direction, I think it was 1984. We got there in 1985. That was when he used the images. As I recall, he was really proposing us a methodology for working with images. So, it was a list of images. And as Oguri said, he would never show us movements. He just gave us the words and let us work with those words. And then, he would see us in rehearsals. And then he would adjust. And, again, to my memory, it was as if he were sculpting or creating the space of the body in space. And in space, that means here with the light, with the set, with the unfolding of time, with others, and I think he was always conscious of the audience’s presence. Whether inside or outside, the question of the audience’s presence was always a big deal. And what I learned most at that time, I think, was the consideration for the audience. And this image work consisted of always searching for ways to give vitality and energy to the pathway of the images, something impossible to stabilize or fix. Impossible to fix it in a form. Even now, if we showed you an image, maybe I suppose Katerina, Oguri and me would probably start looking for bringing this image to life.