Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean-Geoffroy’s contribution is in two parts. On the one hand, a research article, “Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives”, originally published in English under the title “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”, by Vincent-Raphaël Carinola and Jean Geoffroy, in the proceedings of the conference organized by PRISM-CNRS in Marseille (May 2022).

On the other hand, the transcript of a meeting between Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Jean Geoffroy, Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff in Lyon in February 2023.

Access to the two parts and their French versions

First part

Access to the article “On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music”

Access to the French translation “Espaces notationnels et œuvres interactives”

Second part

Encounter with Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff

Access to the French original version of « Rencontre avec Carinola, Geoffroy, François, Sidoroff »

Encounter with

Jean Geoffroy, Vincent-Raphaël Carinola

and

Jean-Charles François, Nicolas Sidoroff

1erFebruary 2023

Translation from French by

Jean-Charles François

(with the help of Deepl.com)

Summary :

1. Origin of the Collaboration

2.1 Toucher Theremin and Agencement

2.2 Toucher, Hands/Ears Correlation

2.3 Toucher, Notation

2.4 Toucher, Form

2.5 Toucher, Process for Appropriating the Piece

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, Smartphones, Primitive Rattle, Virtual Spaces

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, the Path to Virtuosity, Listening

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, a Collaboration Composer/Performer/Computer Music Programmer

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, the “Score”

3.5 To conclude: References to André Boucourechliev and John Cage

1. Origin of the Collaboration

Could you retrace the story of how you met, how did your collaboration come about, and what was its context?

We already worked with Christophe Lebreton[1] on different projects and although Jean and I had often crossed paths, and I knew and admired his work and his various collaborations with composers, I was looking forward to the opportunity to work with him. The point of departure was all the work they had done, Christophe and Jean, on new electronic interfaces and the role of the performer in relationships to them, Jean will be able to tell you more about these projects in detail.

For a concert in Seoul, I had selected some applications taking account for their framework, sound possibilities, possible developments and I had written a short text as an introduction to the concert, in which we also played other pieces by Xavier.

What I realized almost immediately was the possibility of recreating spaces that were different from those imagined by Xavier, and it was equally possible to work on a kind of “sound intimacy”, because in fact, there’s nothing “demonstrative” about playing with a smartphone, you have to lead the audience to enter in the space you’re proposing, and thanks to the different applications deviating from usual utilization and used in different ways, it was as if I had in front of me a new instrument.

In this case, everything stems from the sound and the space it suggests, and then you need a narrative that will enable you to keep a relatively clear framework, since without this framework you run the risk of going round in circles, and playing the smartphones like a child with a rattle…

As with the Light Wall System[4] also designed by Christophe, the most interesting thing, besides music itself, is the absolute necessity of working on a narration, on a form. This should be obvious to any performer, but which is sometimes forgotten it in favor of the instrument, its virtuosity, its placement on stage…

With the SmartFaust applications,[5] the main aim was to return to a sound devoid of « artifice », that would enable us to invite the audience into a totally revisited sound universe.

After this concert, Christophe had the idea of taking his work with smartphones a step further, and then he proposed to Vincent to imagine a piece for “Smart-Hand-Computers – SHC”, a term that better represents this interface than the word “smartphone” which is primarily used to designate a telephone.

From the outset, however, the process was different than with Xavier, if only in terms of creating the sounds. The fact of having two SHCs totally independent of each other with the possibility to include aleatoric elements in the piece and above all, work on the writing of the piece itself made it a totally different project from anything I had done before. Moreover, this piece is an opportunity for us (Christophe and I) to imagine other performing frameworks: we developed a solo version with a set-up similar to that of the Light Wall System, and we’re working on a project for two dancers. Virtual Rhizome by Vincent-Raphaël Carinola really functions as a permanent laboratory, which incites us to constantly revisit the work, which is essential for a performer. These three proposals around the same piece raise the question of our relationships with the audience: from a) the intimacy of a solo with two SHC, b) to a form of address to the public within the Light Wall System framework, and c) to a choreographic piece in which dancers are at the same time performing the music with their body movements.

This piece enables us to re-examine the act of interpretation, which in itself is an exciting question that performers I think don’t often enough consider.

2.1 Toucher, Theremin and Agencement

Raphaël

Following this first experience we wondered whether it would be interesting to write a work for this “instrument”, bearing in mind that from the moment the theremin is connected to a computer, the instrument is definitively no longer a theremin (the more so since its original sound is never heard). The instrument is the theremin connected to a computer, to sounds and sound processing modules distributed around the audience. This is partly the subject matter of the article « On Notational Spaces in Interactive Music »:[8] here the instrument becomes a playing system. What we consider to be the instrument, the theremin, is just one part of the system, which is in fact the “true” instrument. The theremin is equipped with antennas that capture the performer’s gestures, lamps or electronic circuitry that generate a sound that varies according to the distance of the hands from the antennas and, sometimes, in the same cabinet, a loudspeaker is included. This is like electric guitars, there is a kind of amplifier that can be more or less close to the musician. What interests me here is the possibility to dissociate the organological elements of the instrument and turn each component into a writing support. The performer is then confronted with a sort of fragmented object within a system. On the one hand, the performer has to deal with an instrument very different from the traditional one, since he/she doesn’t control everything because part of the sounds are generated by the computer – so, he/she is playing an instrument that has the ability to function on its own – and, on the other hand, the performer has to follow a score which is not entirely constituted by notation on staves. The score also includes the computer program, which contains the sounds I have generated, integrated into the computer’s memory. So, the score itself is scattered across the whole range of media supports: the graphic score of the gestures, that of sounds, the computer program, the interactive programs, and even the “mapping”, that is, the way in which the interface is correlated with the sounds and with the unfolding of the piece in time.

This is why the performer’s work is quite different from that of a performer who is playing an instrument with which he forms a single body, since with this new instrument – as a system – the body tends to be separated from the direct sound production. One part of the way the instrument functions escapes him/her. The performer doesn’t always control the totality of the sounds (since I am the one who generated them as well as the sound processing modules). Moreover, the computer can also function automatically. That’s what’s so interesting, because it means that the way the performer can adapt to the system becomes in itself an object of creation, the object of the composition, and that’s what’s so beautiful. The performer cannot be considered as someone who appropriates a piece fixed on a support, external to her/him, and which she/he then comes to interpret: he/she is part of the work, one component of this “composed” ensemble of interfaces, the computer, the fixed sounds, him, her, the musician, her/his corporeal presence on stage, etc. We face the same type of problem with Virtual Rhizome but addressed in a very different and very strange way.

Here is the video of the version of Toucher by Claudio Bettinelli :

The fact that the situation in which you find yourself partly escapes us could mean some sort of comfort for the performer, but on the contrary, it really disturbed me. This project allowed me to find myself really at the center, first and foremost as a “listener” before being a performer. This requires concentration, to pay attention to all the sound events that you generate, as well as those that you don’t necessarily control and that you need to appropriate and integrate into your “narrative”.

What makes this attitude more sensitive is the fact that, with these instruments, everything seems simple, because just in relation with a movement. Even though the theremin is extremely technical, each person develops his/her own technique, an attitude linked to a form of inner listening to sound, listening that does not pass exclusively through your ears but also through the body.

Raphaël

In fact, what’s very complicated for me with interactive systems in general is that, if everything is determined, that is if the performer can control each sound produced by the machine, she/he becomes some sort of “operator”. The computer takes no initiative, everything must be determined by conditional logic: if-then-else. The computer is incapable of reacting or adapting to the situation, it only does what it’s asked to do, with a very… binary logic. Everything it does, the way it reacts, is limited by the instructions specified in the software program. That’s why you never have the same relationship with the digital instrument as you do with an acoustic one, in which there is a resistance, a physical constraint, linked to the nature of the instrument, which structures gestures and allows the emergence of expression. That’s why the idea of simulating an instrument that escapes the musician’s control, forces the performer to be in a very attentive listening, to be literally on the look-out, to strain the ear, to charge listening with tension. I think that if you want – I don’t know if it’s possible – to be able to find something equivalent to an expression – when I say “expression”, I don’t mean romantic expression or anything like that, it’s something proper to the musician on stage, to the performer, something that belongs only to him or her – you have to find new ways of making it emerge in interaction with the systems, that’s somewhat the idea of inviting the performer to “stretch the ear”.

2.2 Toucher, Hand/Ear Correlations

Raphaël

Then there’s also the process of interaction, on what actual parameters is it possible to act, a volume, a sound form? From there on, you have your “playground” where the hand can develop its movements, intuitively at first, then by exploring the relationship between sound and gesture to give it a singular form of coherence.

Raphaël

2.3 Toucher, Notation

Ultimately, the question is: should we play what’s written or what we read?

This approach changes things considerably. In many pieces you have introductory notes that resemble more instruction manuals, sometimes they are needed, but they become a problem when there is nothing else besides!

When You read Stockhausen’s Kontakte, even without having read the introductory notice, you’re capable to hear the energies that he wrote in the electroacoustic part. In Toucher, as in Virtual Rhizome, we have a very precise structure, and at the same time sufficient indications to leave the performer free to listen and make the piece his or her own, keeping with the limits set by the composer. It’s really this alloy between a predicted sound and a gesture, an unstable equilibrium… but it’s the same thing with Bach.

With pieces like Vincent’s, it’s essential to have this intimate perception: what do I really want to sing, ultimately, what do I want to be heard, what pleases me about it? If you adopt exactly the same attitude behind a marimba or a violin or a piano, you will really achieve as performer something that will be singular, corresponding to a true appropriation of the text you are reading. The idea is to make people hear and think, just as they do when a poem is read: what will be interesting will be the multiplication of the poem’s interpretations, each one allowing the poem to be always in the making, very much alive. It’s exactly the same with music.

Raphaël

2.4 Toucher, Form

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

2.5 Toucher, Process for Appropriating the Piece

Sidoroff

For me, there’s one thing that’s really incredible, it’s the prescience that you can have of a sound, a prescience that is revealed through an attitude, a gesture, a listening. For Virtual Rhizomes, we don’t always know which texture is going to be played, what impact it will have, and the listening and attention that result from this open up incredible horizons because potentially, it compels us to be even more intuitively aware of our own sound sensations. It’s this balance between the attitude of anticipating integral listening, and the notion of form we’ve been working on, that you need to keep in mind, so as not to get into that famous « rattle » Vincent talks about. It’s interesting to think that a texture played that you don’t know a priori will determine the development of this particular sequence, but you still have to give it a particular meaning in terms of space.

During my last years as percussion professor in Lyon, in order to ensure that this particular attention to sound was an essential part in the work on a piece, I wanted no dynamics to appear on the scores I gave to the students, so that they would just relate to the structure, and that the dynamics (their voice) would be completely free during these first readings. At that point, the question of sound and its projection becomes obvious, whereas if you read a written dynamic sign in absolute terms and therefore decontextualized from a global movement, you don’t even think about it, you just repeat a gesture often without paying sufficient attention to the resulting sound.

On the contrary, Toucher and Virtual Rhizome (like other pieces) force us to question these different parameters. For me, Toucher as Virtual Rhizome, are fundamentally methods of music: there are no prerequisites, except to be curious, interested, aware of possibilities, and present! Such freedom offered by these pieces is first and foremost a way of questioning ourselves at all levels: our relationship to form, sound and space, this is why they are true methods of Music. These pieces are proposing a real adventure and an encounter with oneself. On stage, you know pretty much where you want to go, and at the same time everything remains possible, it’s totally exhilarating and at the same time totally stressful.

Raphaël

Right now, one of my students is practicing the piece. He worked on the available online videos to understand it, to understand its notation, etc., which saves time. But that wasn’t the approach used by Jean, who had another kind of experience. I think that each person deals with it in a certain way. But it’s fair to say that, generally speaking, video has become an accessory to the score.

3.1 Virtual Rhizome, Smartphones, Primitive Rattle, Virtual Spaces

Raphaël

When you’re playing a video game, you might find yourself in a room or on the street, and then at some point you take a turn, you go to another room or to another street, and then you’re attacked by some aliens, you’ve to react, and then you move on to the next stage. It’s a sort of virtual architecture in which you can move in many different ways. This was precisely the idea in Virtual Rhizome, to depart from the traditional instrumental model, which still exists in Toucher, but which is no longer appropriate here because there’s no space to explore with this object that is the smartphone. And from this came the idea of building a virtual space and using the smartphone as an interface, almost like a compass, enabling you find your way around this architecture. That’s how the two things, the rattle, and the video game, are linked together.

3.2 Virtual Rhizome, the Path to Virtuosity: Listening

When I recorded with Vincent the percussion sounds used in Virtual Rhizome, I played almost everything with the fingers, the hands, and that allowed for much more color, dynamics, than if I’d played with sticks. When you’re playing with the hands, there is a particular relationship with the material, especially when you’ve spent your entire life playing with sticks, and in fact, when you’re playing with the hands and fingers your listening is even more “curious”.

Then, in this piece, you need to thoroughly understand the interface and play with it, especially with the possibility of superimposing states that can change with each interpretation. But once again, this is only possible with a clear vision of the overall form, if you don’t want to be overwhelmed by the interface.

Whoever the performer is, there is one common thing, which is this necessity to listen: you hear a sound if you go to the bottom of what it has to say. This means writing an electroacoustic piece in real time, with what you hear inside the sound.

It’s the idea of this interiority that helped develop the interpretation, because at the beginning I was moving a lot on stage, and the more I evolved with the piece, the more intimate, singular and secret this approach became. That’s why on stage there is a counter-light (red if possible) so that the public can only see a shadow, and ideally closes the eyes from time to time…

What’s interesting with the versions with dance is that, ultimately, even if the movements are richer and more diversified, there is really this inner listening that predominates, and forces a certain purity, a choice of intention before the choice of movement, that gives rise with the dancers to totally peculiar listening and embodiment movements.

Raphaël

3.3 Virtual Rhizome, a Collaboration Composer/Performer/Computer Music Programmer

With Vincent, everything seemed coherent and flowing, even when we were recording many sounds over the course of a day. Everything was clear to me, and I quickly understood in what sound universe I was going to evolve in, even though I had no idea of the form of the piece, but just knowing the landscape is an essential thing for the performer.

Raphaël

You raised the question of virtuosity earlier, Jean-Charles. Speaking then of virtuality or virtuosity, I liked the link you made between the two. The virtuosity here resides in the fact that there are two smartphones, behaving in complete isolation from each other. They don’t communicate with each other. You could play the piece with only one smartphone, in a way. You could switch from one situation to another, forwards and backwards, using a gestural control. With both of them, you can combine any situation with any other one. This means that you have to work extremely hard at listening, precisely because, on the one hand you don’t always know what automatized sequences will appear, the textures, the layers mentioned by Jean, and on the other hand, you have also controlled sounds, played, each of which can be very rich in itself. The use of two smartphones implies a great deal of complexity because of the multitude of possible combinations. This requires working intensely on an inner concentrated listening, to orient yourself in this virtual universe, which precisely has no physical consistency. There’s no score anymore, the score is in the head, it’s like the Palace of Memory in the Middle-Ages, a purely virtual architecture that you have to explore. That’s why I like the way you link these terms of virtuosity and of virtuality, because each depends on the other, in a way.

Nowadays, with the presence of set-ups, “agencies” [dispositifs], the notion of writing has completely changed its framework, you have to describe the music and at the same time to develop the electroacoustic set-up process of captation, in real time, that is, building an instrument.

The composer can only partly cover the second third, bearing in mind that lutherie also evolves in the writing process… The only obvious thing is that from beginning to end, there is a spoken word, that of the composer, in terms of: “This I want, that I don’t want”. And for me, this is the alpha and omega of creation, that is, its requirement. The composer provides us, performers, with a material, a discourse, a narrative, a vision, a relevance. It’s not a question of hierarchy, but this kind of spoken word is at the heart of the whole process of encounter and creation.

3.4 Virtual Rhizome, the « Score »

Raphaël

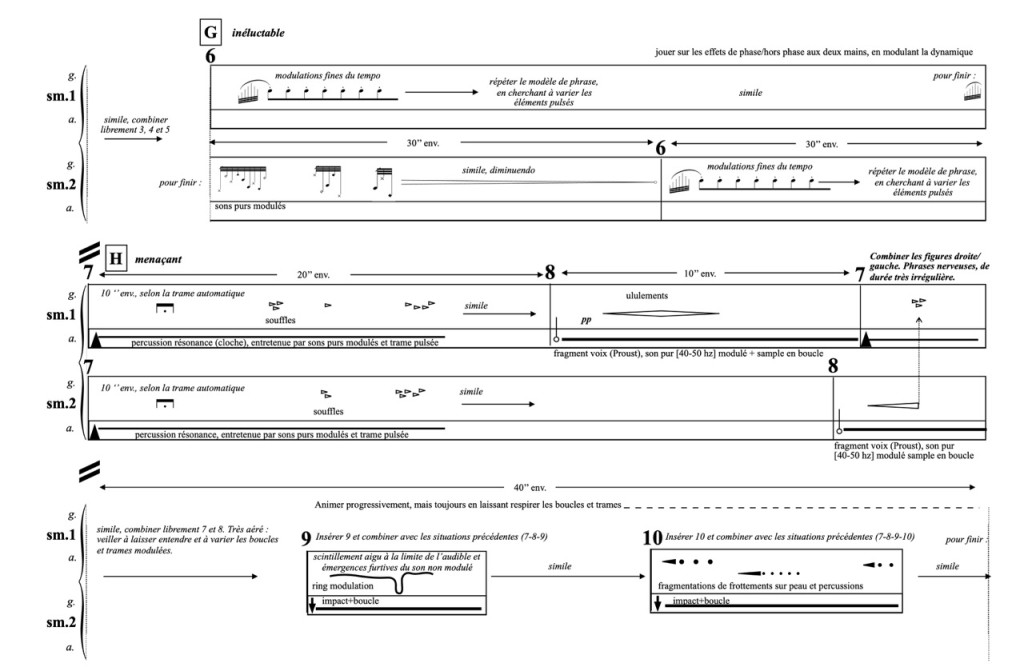

At the top of Figure 3, there’s also a word: “ineluctable”. These terms have been added to produce intentionality. The performer doesn’t just generate sounds, she/he animates them, gives them a soul, literally, and to give them a soul requires an intention, a meaning. It might be a concept, I don’t know, a geometric figure, something that generates intentionality. This is important in the score, but what is notated is actually a possible pathway, and this is the result therefore of the performer’s work, it’s a pathway followed by the performer during the collaboration, and which becomes a possible model for the piece’s realization. It’s interesting to note that it is this pathway that was followed by other performers who played it, as if the form was definitively fixed.

Raphaël

Raphaël

Raphaël

3.5 Conclusion: References to André Boucourechliev and John Cage

Raphaël

Raphaël

1.Christophe Lebreton : « Musicien et scientifique de formation, il collabore avec Grame depuis 1989. » Musician and educated as a scientist, he collaborates with Grame since 1989.

See: Grame

2. Xavier Garcia, musician, Lyon : Xavier Garcia

3. Charles Juliet, Rencontres avec Bram Van Velde, P.O.L., 1998.

4. « Light Wall System was developed in LiSiLoG by Christophe Lebreton and Jean Geoffroy. See LiSiLoG, Light Wall System

5. SmartFaust is both the title of a participatory concert and the name of a set of applications for smartphones (Android and Iphone) developed by Grame using the Faust language. See Grame, Smart Faust.

6. Claudio Bettinelli, percussionist, Saint-Etienne. See Claudio Bettinelli.

7. Vincent-Raphaël Carinola, Typhon, the work is inspired by Joseph Conrad’s story Typhon. See Grame, Typhon.

8. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, 2.3, 2nd paragraph.

9. Thierry De Mey, Silence Must Be: “In this piece for solo conductor, Thierry De Mey continues his research into movement at the heart of the musical ‘fact’… The conductor turns towards the audience, takes the beat of his/her heart as pulsation and begins to perform increasingly complex polyrhythms, …3 on 5, 5 on 8, getting close to the golden ratio, she/he traces the contours of a silent, indescribable music…”. Grame

10. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, op. cit. 3.1.

11. Thierry de Mey, Light music: “musical piece for a ‘solo conductor’, projections and interactive device (first performance March 2004 – Biennale Musiques en Scène/Lyon), performed by Jean Geoffroy, was produced in the Grame studios in Lyon and at the Gmem in Marseille, where Thierry De Mey was in residence.” Grame

12. Jorge Luis Borges, Fictions, trad. P. Verdevoye et N. Ibarra, Paris : Gallimard, 1951, 2014.

13. “On Notational Spaces and Interactive Works”, op. cit. 3.2.

14. See Monique David-Ménard, « Agencements déleuziens, dispositifs foucaldiens », in Rue Descartes 2008/1 (N°59), pp. 43-55 : Rue Descartes

Jean-Charles François – English

Return to the original text in French: Invention collective

Collective Invention in Music

and Encounters Between a Diversity of Cultures

Jean-Charles François

Summary:

1. Introduction

2. Alternative forms to definitive art works

3. Improvisation

4. Artistic Processes or just Human Interactions?

5. Protocols

6. Conclusion

Introduction

The world in which we live can be defined as one in which a great diversity of practices and cultures coexist. As a result, it is difficult today to think in terms of the modern Western world, Eastern philosophy, African tradition or other labels too easy to use to guide us in the chaos of the world. We are in presence of an infinite number of networks, and each of us is active in more than one of these. Therefore, we have to think about musical practices in terms of ecological problems. A practice can kill another one. A practice can depend directly on another’s survival. A practice can be directly connected to another and still be different. The ecology of practices (see Stengers 1996, Chapter 3) or how to face a potentially very violent multicultural world is probably today as important as the ecological question of the future of the planet earth. I will attempt in this article to treat one aspect of the diverse world of artistic practices: improvisation with heterogeneous groups.

My own personal research on mediation between groups of musicians belonging to different cultural practices or musical styles stems from my involvement as the director (between 1990 and 2007) of a center devoted to the training of music school teachers, the Cefedem AuRA in Lyon, France. This institution was created in 1990, under the authority of the Ministry of Culture, and offers a two-year program leading to the Music Teacher State Diploma [Diplôme d’État de professeur de musique], geared towards the teaching of voice, instruments, basic musicianship, choral conducting, jazz, popular music [described in France as Musiques actuelles amplifiées, Today’s Amplified Music], and traditional music in music schools and conservatories organised throughout France by the towns. Research was conducted within the framework of curriculum development in this institution, in direct collaboration with Eddy Schepens and the entire pedagogical and administrative team of this institution.

For the first ten years all the students at the Center were classical musicians issued from Regional Conservatories. In 2000, the study program was completely reinvented to accommodate the inclusion of jazz, popular music, and traditional music students, alongside the ones from the “classical” sector. The curriculum was based on two distinct imperatives: (a) each musical genre had to be recognized as autonomous in its practical and theoretical specificities; and (b) each musical genre had to collaborate with all the others in specific artistic and pedagogical projects. We were thus confronted with the issue of how to face the problem of a difference of culture between a highly formalised teaching tradition with low exposure to public presentations, and traditions that are based on atypical or informal forms of learning involving a high degree of immediate public interactions. The problem that then had to be solved can be formulated as follows : the classical sector tends to develop an instrumental or vocal identity in a posture of technical readiness to play any music (on the condition that it would be written on a score) ; other musical genres tend to require of their members a strong identity based on the style of music as such accompanied by a technical approach based solely on what is necessary to express that identity. Our task was to find solutions that could include all the ingredients of this triple equation. Two concepts emerged: a) the curriculum would focus on student projects rather than on a series of courses and the definition of their content (although these courses continued to exist); b) projects should be based on the principle of a contract binding students to a number of constraints determined by the institution and on which evaluation would be based. The Centre has developed a research program on these issues and in pedagogy of music, and publishes a journal, Enseigner la Musique (see for example François & al. 2007).

Taking this concept of intercultural encounters as a model, experimental situations have been carried out by a Lyon collective of artists in existence since 2011: PaaLabRes (Artistic Practices in Acts, Laboratory of Research [Pratiques Artistiques en Actes, Laboratoire de Recherche]).

Several projects were developed:

- A small group of improvisators met to propose protocols for developing common material in the context of collective invention[1]. These protocols were tested, discussed and then tried in a number of workshops addressed to the largest range of participants (professionals, amateurs; beginners and advanced students; musicians and dancers belonging to different musical categories, styles and traditions) (2011-2015).

- Regular meetings of PaaLabRes musicians with dancers (Maguy Marin’s Company members among others) have been organized at the Ramdam, an arts center near Lyon, with the aim of developing common materials between dance and music in improvisation (2015-2017).

- Through the digital space www.paalabres.org a reflection on the definition of artistic research, situated in between formal academic research and artistic practices, between various artistic domains and diverse aesthetic expressions, in between pedagogy and performance on stage. (See the station Débat, line “Artistic Research in the first edition of paalabres.org).

2. Alternative forms to definitive art works

Improvisation situations seem in this context to be a good way to deal with heterogeneous encounters through practicing music, not so much as a focusing on aesthetics values, but rather as a democratic process that this situation seems to promote: each person is fully responsible for her or his sound production and for interacting with the others persons present in the space, and also with the diverse means of production available.

The definition of improvisation, within the art practices of the West—especially in its “freer” forms— is often proposed as an alternative to the written music that dominated European art music for at least two centuries. Improvisation faced with the structuralism of the 1950-60s tended to propose a simple inversion of the prevailing model:

- The performer considered up to that time as not being a major participant to the creation of major works, becomes through improvisation completely responsible for her/his creation in a context that changed the definition of work of art.

- The practice of writing signs on a score and respecting them in interpretation is replaced by the absence of any visual notation and the prevalence given to oral communication.

- There will be no more works definitively fixed in historical memory, but processes that are continuously modified ad infinitum.

- The slow reflective method used by the composer in a private space when elaborating a given piece of music will be replaced by an instantaneous act, in the spirit of the moment, on stage and in the presence of an audience.

- Instead of having compositions that define themselves as autonomous objects articulating their own language and personal sleight of hand, free improvisation will tend to go in the direction of the “non-idiomatic” (see Bailey 1992, p. ix-xii)[2] or towards the “all-idiomatic” (the capacity to borrow sound material from any cultural domain).

And so on, all the terms being inverted.

For this inversion to occur, however, some stable elements have to remain in place: notably the concept that music is played on stage by professional musicians before an audience of educated music lovers. This historical stability of the concert performance largely inherited from the 19th century goes hand in hand according to Howard Becker with what he calls a “package”: an hegemonic situation that controls in a global way all the actions in a given domain with particular economic conditions, definitions of professional roles and supporting educational institutions (see Becker 2007, p. 90). The reversal of elements appears to guarantee that certain aesthetical attitudes would remain unchanged: for example, the concept of “non-idiomatic” might be considered as reinforcing the modernist view of an ever-changing process towards new sounds and new sound combinations. We don’t know which idiom will result from the composer’s work, but the ideal is to arrive at a personal idiom. The improviser should come on stage without idiomatic a-priori, but the result will be idiomatic only for the duration of the concert. The “blank slate” ideal persists in the idea that each improvisation has to occur outside beaten paths.

The nomadic and transverse approach to improvisation cannot be confined to the idea that it is an alternative to sedentary human beings personified by the classical musicians of the West. The nomadic and the transverse practices cannot just pretend to offer an alternative to institutional art forms, through their indeterminate movements and infinite wanderings. Rather the (transversal) nomads have to deal with the complex knots of practices situated in between oral and written communication, timbre and syntactic articulation, spontaneity and predefined gestures, group interactivity and personal contribution.

3. Improvisation

One of the strong frameworks of improvisation – as distinct from written music on scores – is the shared responsibility between players for a collective creative sound production. However, the exact content of this collective creativity in actual improvisations seems unclear. In improvisation, the emphasis is on the unplanned public performance on stage, on the ephemeral act that happens only once. The ideal of improvisation seems to be dependent on the absence of preparation, before the act itself. And at the same time, the actual act of improvisation cannot be done by participants who are not “prepared” to do it. The performance may be unprepared in the details of its unfolding, but generally speaking it cannot be successfully carried out without some intense preparation. This is indeed the paradox of the situation.

Two models can be defined, and we have to remember that theoretical models are never reflecting reality, but they offer different points of reference allowing us to reflect on our subject matter. In the first model the individual players undergo an intensive preparation inscribed in a time frame of many years, in order to achieve a personal voice, a unique manner of producing sound and gestural acts. This personal voice, or manner of playing, has to be inscribed in memory – inscribed in the body – in a wide-ranging repertoire of possibilities. This is the principal condition of the improvisation creative act: the creative elements are not inscribed on an independent support – like a score – but they are directly embodied in the playing capacities of the performer. The players meet on stage as separated individuals in order to produce something together in an unplanned manner. The performance on stage will be the superimposition of personal discourses, but if players can anticipate what the partners will be able to produce (above all if they have already played together or listen to their respective performances), they will be able to construct together, within that unplanned framework, an original sonic and/or gestural world. The emphasis on individual preparation seems to not hinder the constitution of a fairly homogeneous network of improvisators. This network is geographically very large and imposes, without having to specify any definition, the conditions of its access by a set of implicit unwritten rules. What is at stake here? The main focus of this model is on the public performance on a stage, where the important issues concern the sonic or gestural quality of the acts in that encounter produced by everybody present, including the attitudes and reactions of the audience.

The other alternative model puts the emphasis on a collective co-construction of the sonic universe independently from any eventual presentation on stage or other types of interactive actions. It implies that a substantial time is spent on elaborating a repertoire of sonic (or any other) materials within a permanent group of people. The development of the collective sound depends on a sufficient number of sessions working together with all members present. That these sessions are performed before an audience or not, is beside the point. This second model does not present much interest if the members of the group are homogeneous in their background, notably if they acquired their professional status in the same kind of educational institutions and the same processes of qualification. If they are not different in some important respect, the first model seems to be more adequate, as there is no difficulty in building a collective sound world directly through improvised performance on stage. But if they are different, and above all if they are very different, the idea of building a collective sound material, or a collective artistic material, is not a simple task. On the one hand, the differences between participants have to be maintained, they have to be strictly respected in mutual terms. On the other hand, building something together will imply that each participant is ready to leave behind reflexes, habits, and traditional ways of behavior. This is a first paradoxical situation. Another paradox immediately becomes apparent adding to the complication: on the one hand, the material that is collectively developed has to be more elaborate than just the superimposition of discourses in order to qualify as co-constructions; and, on the other hand, the material should not become fixed in a structuration, as would be the case with a written composition, the material should remain open to improvisation manipulations and variations, to be realized at the actual moment of the improvisation performance. The performers should remain free to interact as they see fit on the spirit of the moment. This second model does not exclude public performance on stage but cannot be limited to this obligation. It is centered on collective processes and might involve other types of social output and interactions.

The challenges of the second model are directly linked to debates about the means to be developed in order to break down the walls. To face these challenges, it is not enough to just gather people of different origins or cultures in the same room and expect that more profound relationships will develop. It is also not sufficient to invent new methodologies appropriate for a given situation, to ensure that a miracle of pacific coexistence will occur. In order to face complexity, you need to develop situations in which you should have a number of ingredients:

- Each participant has to know in practical ways what all the other participants are about.

- Each participant is obligated to follow collective rules decided together.

- Each participant should retain an important margin of personal initiative and remains free to express differences.

- There can be processes in which a leadership can emerge, but on the whole the context should remain on a democratic level.

All this complexity demonstrates the virtues of pragmatic tinkering within the framework of this plan of action.

As the sociologist and jazz pianist David Sudnow showed when he described the learning processes of his hands that enabled him to produce jazz improvisations: sound and visual models, although essential to the definition of objectives to be attained, are not sufficient to produce real results through simple imitation:

When my teacher said, “now that you can play tunes, try improvising melodies with the right hand,” and when I went home and listened to my jazz records, it was as if the assignment was to go home and start speaking French. There was this French going on, streams of fast-flowing strange sounds, rapidly winding, styles within styles in the course of any player’s music. (Sudnow 2001, p. 17)

Some degree of “tinkering about” is necessary to allow the participants to achieve their purposes through heterogeneous detours of their own, outside the logical framework given by the teacher.

The idea of dispositif (apparatus, plan of action) associated with “tinkering about” corresponds to the definition found in the dictionary: an “ensemble of means disposed according to a plan in order to do a precise action”. One can refer to the definition given by Michel Foucault as “a resolutely heterogeneous ensemble, comprising discourses, institutions, architectural amenities, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative arrangements, scientific enunciations, philosophical, moral and philanthropic statements, some explicitly stated, some implicitly unsaid…” (Foucault 1977, see also the station timbre, line “Improvisation” in the first edition of paalabres.org)

In applying this idea to a co-production of sonic or gestural materials in the domain of artistic practices, the institutional elements of this definition are indeed present, but the emphasis is here directed towards the network of the elements created through everyday action, which are contextualized by given agents and materials. Thus, the means are defined here as concerning, at the same time, the persons concerned, their social and hierarchical status within a given artistic community, the materials, instruments and techniques that are provided or already developed, the spaces in which the actions take place, the particular interactions – formalized or not – between participants, between participants and materials or techniques, and the interactions with the external world outside the group. The dispositifs are more or less formalized by charters of conduct, protocols of action, scores or graphic images, rules pertaining to the affiliation to the group, evaluation processes, learning and research procedures. To a great extent, however, the dispositifs are governed on an everyday basis in an “oral” manner, in contexts that can change radically according to circumstances, and through interactions, which by their instability can produce very different results.

4. Artistic Processes or just Human Interactions?

The idea of dispositif, or complex apparatus, at the same time denies that artistic acts be simply limited or confined to well identified autonomous objects, and it also enlarges considerably the scope of artistic endeavours. The network that continuously forms, informs and deforms itself cannot be limited to a single focus on the production of artistic materials for the benefit of a public. The processes are no longer defined in specific specialized spaces. The term improvisation is no longer strictly limited to a series of sacred principles of absolute freedom and spontaneity or, on the contrary, respect for any tradition. Improvisation can incorporate activities that involve a variety of media supports – including using writing on paper – to achieve results in particular contexts. The purity of clear and definitive positions can no longer be what should dictate all possible behaviour. This does not mean that ideals have been erased and that the values that one wants to place at the forefront of the reality of practices have lost their primordial importance.

The confrontation of nomadic and transverse artistic practices to institutional imperative requirements may concern many areas: improvisation, research, music and art education, curriculum design, reviving traditional practices, etc. More and more artists find themselves in a situation in which their practice in strictly artistic terms is now considerably widened by what we call “mediation”, or mediating between a diversity of elements (see Hennion 1993 and 1995): pedagogical activities, popular education, community involvement, public participation, social interactions, hybrid characteristics between artistic domains, etc. The immersion of artistic activities into the social, educational, technological and political realms implies the utilization of research tools and of research partnerships with formal institutions as a necessary part of the elaboration of artistic objects or processes (see Coessens 2009, and the PaaLabRes’ station the artistic turn). Research practices in artistic domains need to a large extent the legitimacy and evaluation given by academic bodies, but it is equally important to recognize that they must be seen as part of an “eccentric science” (see Deleuze & Guatarri 1980, pp. 446-464), which considerably changes the meaning of the term “research”. The important questioning of these artists pertains directly to the very practice of conducting research: it tends to attempt to erase the usual strict separation between actors and observers, between the scientific orientation of the publication of results and other informal forms of presentation, and between the artistic act and reflections about it.

A possible nomadic and transverse response would be found along a pathway between the freedom of creative acts and the strict imposition of traditional canons. In this context, the creative act can no longer be seen as a simple individual expression asserting freedom in relation to a fiction of universality. The constitution of a particular collective, defining its own rules along the way, must play, in an unstable friction, against individual imaginative desires. To place somebody in a situation of research would mean to anchor the creative act on the formulation by a collective of a problematical process; the complete freedom of creation is now bound by collective interactions and to what is at stake in the process, without being limited by the strict rules of a given model. The creative act would cease to be considered as an absolute object in itself, and the accent would be put on the numerous mediations that determine it as a particular aesthetical and ethical context: the convergence at a certain moment of a number of participants into some form of project. The knots of this convergence need to be explicated not in terms of a particular desired result, but in terms of the constitution of some kind of chart of the problematic complexity of the situation at its inception: a system of constraints which deals with the interaction between materials, spaces, institutions, diverse participants (musicians, administrators, amateurs, professionals, theoreticians, students, general public, etc.), resources at hands, references, etc. According to Isabelle Stengers, the idea of constraint, as distinct from “conditions”, is not an imperative imposed from outside, nor a way to institute some legitimacy, but it requires to be satisfied in an undetermined manner open to many possibilities. The signification is determined a posteriori at the end of a process (Stengers 1996, 74). Constraints have to be taken into account, but do not define pathways that might be taken for the realization of the process. Systems of constraints apply best when very different people with different specialized fields are called to develop something together.

5. Protocols

We have called “protocols” collective research processes that take place before an improvisation and that will colour its content, then accumulate in the collective memory a repertoire of determined actions. The detail of this repertoire of actions is not fixed, nor is it necessarily decided that a given repertoire should be called up during an improvisation. The definition of the term protocol is obviously ambiguous and for many will seem to go completely against the ethics of improvisation. The term is linked to connotations of official, even aristocratic circumstances, where behaviour considered acceptable or respectable is completely determined: it refers to socially recognised modes of behaviour. Protocol is also used in the medical world to describe series of care acts to be followed (without omissions) in specific cases. It is not in the sense of these various contexts that we use the term.

The definition of protocol is here linked to written or oral instructions given to participants at the beginning of a collective improvisation that determine rules governing the relationships between persons or that define a particular sound, gestural or other type of material. It corresponds more or less to what you may find in dictionary (here French Larousse dictionary on-line): “Usages conformed to relationships between people in social life” and “Ensemble of rules, questions, etc. defining a complex operation”. The participants have to accept that in a limited time, some interaction rules in the group would be determined with the aim of building something together or to understand another point of view, to enter into playing with the others. Once these rules are experimented, when situations have been built, the protocol in itself can be forgotten in order that interactions less bound by rules of behaviour can take place, retrieving then the spirit of unplanned improvisation. The ideal, when determining a protocol, is to seek a collective agreement on its specific content, on the exact formulation of the rules. In fact, this rarely takes place in real situations, as different people understand rules in different ways. A protocol is most often proposed by one particular person, the important factor is to allow all present the possibility to propose other protocols, and also to be able to elaborate variations on the proposed protocol.

The contradiction that exists between the intensive preparation that improvisers impose on themselves individually and improvisation on stage that takes place “without preparation”, is now found at the collective level: intensive preparation of the group of improvisers must take place collectively before spontaneous improvisation can take place, using elements from the accumulated repertoire but without planning the details of what is going to happen. If the members of the collective have developed materials in common, they can now more freely call them up according to the contexts that arise during improvisation.

Thus we are in the presence of an alternation between, on the one hand, formalized moments of development of the repertoire and, on the other hand, improvisations which are either based on what one has just worked on or, more freely, on the totality of the possibilities given by the repertoire and also by what is external to it (fortuitous encounters between individual productions). The objective remains therefore that of putting the participants in real improvisational situations where one can determine one’s own path and in which ideally all the participants are in specific roles of equal importance.

Different types of protocols or procedures can be categorized, but care should be taken not to catalogue them in detail in what would look like a manual. In fact, protocols must always be invented or reinvented in each particular situation. Indeed, the composition of the groups in terms of the heterogeneity of the artistic fields involved, the levels of technical (or other) ability, age, of social background, geographical origin, different cultures, particular objectives in relation to the group’s situation, etc., must each time determine what the protocol proposes to do and therefore its contextual content.

Here are some of the categories of possible protocols among those we have explored:

- Coexistence of proposals. Each participant can define a particular sound and/or gestural movement. Each participant must maintain his or her own elaborate production throughout an improvisation. Improvisation therefore only concerns the temporality and the level of personal interventions in superimpositions or juxtapositions. The interaction takes place at the level of a coexistence of the various proposals in various combinations chosen at the time of the improvised performance. Variations can be introduced in the personal proposals.

- Collective sounds developed from a model. Timbres are proposed individually to be reproduced as best they can by the whole group in order to create a given collective sound.

- Co-construction of materials. Small groups (4 or 5) can be assigned to develop a coherent collective sound or body movements. The work is envisaged at the oral level, but each group can choose its own method of elaboration, including the use of paper notations. Then teach it to other groups in the manner of their choice.

- Construction of rhythmic structures (loops, cycles). The characteristic situation of this kind of protocol is the group arranged in a circle, each participant in turn (in the circle) producing an improvised short sound or gesture, all this in a form of musical “hoquet”. Usually the production of the sounds or gestures that loop in the circle is based on a regular pulse. Variations are introduced by silences in the regular flow, superimposing loops of varying lengths, rhythmic irregularities, etc.

- Clouds, textures, sounds and collective gestural movements – individuals drowned in the mass. Following the model developed by a number of composers of the second half of the twentieth century such as Ligeti and Xenakis, clouds or sound textures (this applies to gestures and body movements as well) can be developed from a given sonority distributed randomly over time by a sufficient number of people producing them. The collective produces a global sound (or global body movements) in which the individual productions are blended into the mass. Most of the time, improvisation consists in making the global sound or the movements evolve in a collective way towards other sound or gestural qualities.

- Situations of social interaction. Sounds or gestures are not defined, but the way of interacting between participants is. Firstly, there is the situation of moving from silence to collectively determined gestural and bodily movements (or to a sound), as in situations of warm-up or early stages of improvisation in which effective improvised play only begins when all participants have agreed in all senses of the word tuning : a) that which consists of instruments or bodies being in tune, b) that which concerns the collective’s test of the acoustics and spatial arrangement of a room to feel together in a particular environment, c) that which concerns the fact that the participants have agreed to do the same activity socially. This is for example what is called the prelude in European classical music, the alãp in North Indian classical music, a process of gradual introduction into a more or less determined sound universe, or to be determined collectively. Secondly, one or more actions can be prohibited in the course of an improvisation. Thirdly, the rules of the participants’ playing time, or of a particular structuring of the temporal course of the improvisation can be determined. Finally, one can determine behaviours, but not the sounds or gestures that the behaviours will produce.

- Objects foreign to an artistic field, for example, which have no function of producing sounds in the case of music, may be introduced to be manipulated by the collective and indirectly determine the nature of the sounds or gestures that will accompany this manipulation. The example that immediately comes to mind is that of the sound illustration of silent films. But there are an infinite number of possible objects to use in this situation. The attention of the participants is mainly focused on the manipulation of the object borrowed from another domain and not on the particular production of what the usual discipline requires.

6. Conclusion

The two concepts of dispositif and of system of constraints seem to be an interesting way to define artistic research, especially in the context of heterogeneous collective creative projects: collective improvisation, socio-political contexts of artistic acts, informal/formal relationships to institutions, Questions of transmission of knowledge and know-how, various ways of interacting between humans, between humans and machines, and between humans and non-humans. This widens considerably the scope of artistic acts: curriculum design, interdisciplinary research projects, teaching workshops (see François & al. 2007), become, in this context, fully-fledged artistic situations outside the exclusivity of performances on stage.

Today we are confronted with an electronic world of an extraordinary diversity of artistic practices and at the same time a multiplication of socially homogeneous networks. These practices tend to develop strong identities and hyper-specializations. This urgently forces us to work on the meeting of cultures that tend to ignore each other. In informal as well as formal spaces, within socially heterogeneous groups, ways of developing collective creations based on the principles of direct democracy should be encouraged. The world of electronic technologies increasingly allows access for all to creative and research practices, at various levels and without having to go through the institutional usual pathways. This obliges us to discuss the ways in which these activities may or may not be accompanied by artists working in formal or informal spaces. The indeterminate nature of these obligations – not in terms of objectives, but in terms of actual practice – brings us back to the idea of nomadic and transversal artistic acts.

1. The following musicians participated to this project: Laurent Grappe, Jean-Charles François, Karine Hahn, Gilles Laval, Pascal Pariaud et Gérald Venturi.

2. Derek Bailey defines “idiomatic” and “non-idiomatic” improvisation as a question of identity to a cultural domain, and not so much in terms of language content: “Non idiomatic improvisation has other concerns and is more usually found in so-called ‘free’ improvisation and , while it can be highly stylised, is not usually tied to representing an idiomatic identity.” (1992, p. xii)

Bibliographie

Bailey, Derek. 1992. Improvisation, its nature and practice in music. Londres: The British Library National Sound Archive.

Becker, Howard. 2007. « Le pouvoir de l’inertie », Enseigner la Musique n°9/10, Lyon: Cefedem AuRA – CNSMD de Lyon. This French translation is extracted from Propos sur l’Art, pp. 59-72, paris: L’Harmatan, 1999, translation by Axel Nesme.

Coessens, Kathleen, Darla Crispin and Anne Douglas. 2009. The Artistic Turn, A Manifesto. Ghent : Orpheus Institute, distributed by Leuven University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles et Felix Guattari. 1980. Mille Plateaux. Paris : Editions de Minuit.

François, Jean-Charles, Eddy Schepens, Karine Hahn, and Dominique Clément. 2007. « Processus contractuels dans les projets de réalisation musicale des étudiants au Cefedem Rhône-Alpes », Enseigner la Musique N°9/10, Cefedem Rhône-Alpes, CNSMD de Lyon, pp. 173-194.

François, Jean-Charles. 2015a. “Improvisation, Orality, and Writing Revisited”, Perspectives of New Music, Volume 53, Number 2 (Summer 2015), pp. 67-144. Publish in French in the first edition of paalabres.org, station timbre with the title « Revisiter la question du timbre ».

Foucault, Michel. 1977. « Entrevue. Le jeu de Michel Foucault », Ornicar, N°10.

Hennion, Antoine. 1993. La Passion musicale, Une sociologie de la médiation. Paris : Editions Métailié, 1993.

Hennion, Antoine. 1995. « La médiation au cœur du refoulé », Enseigner la Musique N°1. Cefedem Rhône-Alpes and CNSMD de Lyon, pp. 5-12.

PaaLabRes, collective. 2016. Débat on the line “Recherche artistique”, a debate organized by the PaaLabRes collective and the Cefedem Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes in 2015.

Stengers, Isabelle. 1996. Cosmopolitiques 1: La guerre des sciences. Paris: La Découverte / Les empêcheurs de penser en rond.

Stengers, Isabelle. 1997. Cosmopolitiques 7: Pour en finir avec la tolerance, chapter 6, “Nomades et sédentaires?”. Paris: La Découverte / Empêcheurs de penser en rond.

Sudnow, David. 2001. Ways of the Hand, A Rewritten Account. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT