Nomadic Collective Creation

As part of the “Biennale Hors Norme”, Lyon

September 15-23

At the Grandes Voisines,

Lyon Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse,

and Lyon II « Lumière » University,

Review of observations from workshops organized by

l’Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p

Texts by Joris Cintéro, Jean-Charles François

and

Giacomo Spica Capobianco and Sébastien Leborgne for Cra.p

l’Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p

Translation from French by Jean-Charles François.

Summary :

Part I: The Project of the Orchestre National Urbain « Nomadic Collective Creation »

1.1 The project of the Orchestre National Urbain

1.2 Period of Preparation of the Project

Part II : The Grandes Voisines

2.1 Workshops at the Grandes Voisines

2.2 The Collective Workshop « Sound Laboratory » at the Grandes Voisines

2.3 Cello/Painting Workshop at the Grandes Voisines

2.4 Trombone Workshop at the Grandes Voisines

Part III : The Project at the Lyon CNSMD

3.1 Meetings during the Project

3.2 The « Sound Laboratory » Workshop at the CNSMDL

3.3 The Human Beat-Box Workshop

3.4 Public Presentation of the Work in the Conservatorium Court yard.

3.5 Reviewing the project on October 10, 2023 at the Lyon CNSMD

Part IV : The Project at Lyon II « Lumière » University

4.1 Morning of September 31 at Lyon II University

4.2 The Workshops at Lyon II University

4.3 The Workshop « Sound Laboratory » in the Lyon II University Amphitheatre

4.4 The Public Presentation of the Work at Lyon II « Lumière » University

Part V : The Aesthetic Framework of the Idea of Collective Creation

Conclusion

Part I : The project of the Orchestre National Urbain,

“Nomadic Collective Creation”

In the following article, we describe a deliberately personal account of how we perceived the process during the workshops organized by the “Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p as part of the “Nomadic Collective Creation” project. This project took place on September 15-21, 2023, as part of the “Biennale Hors Norme” at the Grandes Voisines in Francheville near Lyon, the Lyon Conservatoire National Sipérieur de Musique et de Danse (CNSMD) and the Lyon II « Lumière » University. The Biennale Hors Norme takes place in Lyon every 2 years. The philosophy of this event is “to do with the other”.

Joris Cintéro’s account covers the period of preparation for the project and the day of September 15 at the Grandes Voisines. He describes his way of proceeding in this way:

As I took hardly any notes that day (I attended explicitly in the spirit of participation), the following report is based essentially on my memories. Writing in this way allowed me to dig up these memories, alongside the photos and videos I took during the day – which also helped me to ‘recover’ my memory. This report therefore alternates between descriptions, contextualisation and snippets of analysis that need to be explored in greater depth.

Jean-Charles François’ report is based on a day spent at the Lyon CNSMD, on September 19 and two days at the Lyon II University, on September 21 and 22. It was compiled from observations (without participation in the activities) and note-taking.

In both cases, the reports alternate descriptions, contextualizations and analytical fragments that need to be explored in greater depth.

Giacomo Spica Capobianco and Sébastien Leborgne, members of the Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p, provide some essential background information for understanding their approach.

Interspersed with the texts are extracts from a video realized by the Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p team, featuring interviews with diverse participants and segments of the workshop proceedings.

1.1 The project of the Orchestre National Urbain

Jean-Charles François :

The “Nomadic Collective Creation” project was developed by Giacomo Spica Capobianco, for the Hors Norme 2023 Biennial. Giacomo is the artistic director of Centre d’art – Musiques urbaines – Musiques électroniques (Cra.p) [Art center – Urban Music – Electronic Music], which he founded over thirty years ago. According to its website “The CRA.P team aims to exchange knowledge and know-how in the domain of urban and electro music, to cross aesthetics and practices, to generate encounters, to invent new forms, to create artistic clashes, and to give people the means to express themselves.” (Cra.p). The project has been developed in collaboration with the members of the Orchestre National Urbain, the FEM team directed by Karine Hahn, “Formation à l’Enseignement de la Musique” (Music teachers training) as part of the Conservatoire Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Lyon (CNSMDL – FEM), and with visual artist Guy Dallevet for the Hors Norme Biennial.(BHN).

The description of the project by its organizers can be summarized with several elements regrouped in a scheme aimed in a general way at getting very different groups of people to work collectively to produce music, dance and painting:

- Three axes of mediation are here combined: a) invite in the same space very different social groups; b) invite in the same space people who can be qualified to call themselves “artists” (conservatory students) with people who, a priori, have no recognized skills in this domain; c) invite in the same space practices in different artistic domains (music, dance, theatre, visual arts, poetry).

- The encounters are based on immediate artistic practices, making music, making dance, making painting. To ensure that this common practice does not give one group an advantage over another, the encounters are organized in such a way that everyone will have to be confronted with tasks that are completely new to them, as for example playing trombone for the first time in your life, or dancing if you’re a musician.

- The project is structured in a series of workshops led by members of the Orchestre National Urbain:

Sébastien Leborgne (Lucien 16’s), beat box and spoken voice.

Rudy Badstuber Rodriguez, MAO and percussion elements.

Selim Penaranda, cello.

Odenson Laurent, trombone.

Sabrina Boukhenous, body movements.

Clément Bres, drums.

Giacomo Spica Capobianco, Sound Laboratoire, a workshop regrouping after the other workshops all their activities, in the perspectives of collective creation.

The painting workshops are led by Guy Dallevet for the Hors Norme Biennial.

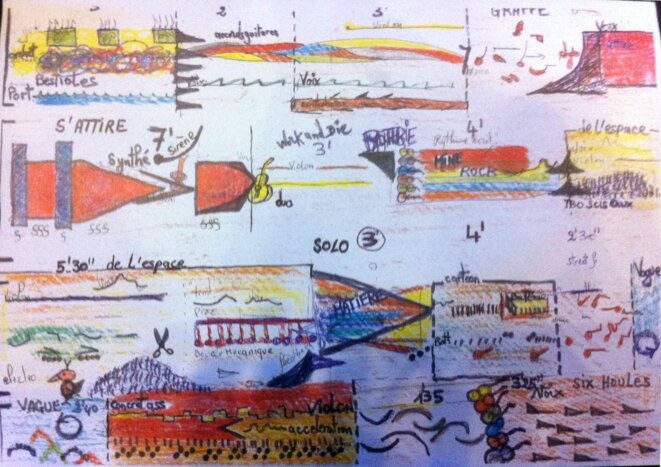

The common thread running through these very different workshops (except painting) in terms of material manipulations, is made of a series of color codes defining playing modes:

a) orange = strong wind ;

b) white = gradual slowing down ;

c) red = repeated rhythm (three quarter notes and a rest);

d) brown = 8 regular pulsations;

e) black = freeze, silence;

f) blue = fear, shivering, energy;

g) green = free improvisation.

The various effective practices in different workshops are all based on the exploration of these color codes.

- Another important activity initiated by the Orchestre National Urbain, is the writing of personal texts to be spoken (in precise rhythms or freely) when all the elements from the workshops meet on stage.

- All participants follow all the workshops one after another, and then everybody meets in a general ensemble with the following stations: trombone, cello, amplified voice, drum set, various suspended sounding objects, 2 electronic stations (loops, playing with fingers on a pad), a “spicaphone” (a kind of electric guitar with a single string built by Giacomo Spica), an instrument with strings stretched on a metal frame (called « sound mirror »), an electric guitar set up horizontally to be played like a percussion instrument, a space for dance. A conductor is chosen among the participants to organize the performance, showing along the way color-coded cards. In Giacomo’s mind, this is not the equivalent of “sound painting”, the conductor must only show the color without imposing any particular energy. Experience with the set-up has shown that, in practice, the people conducting (members of the Orchestre National Urbain as well as any other participants) often exert a “particular energy” – bending down to embody a soft intensity, to play at changing the color-code cartons very quickly, ensuring that only one part of the ensemble be concerned with a color-code, etc.)

- At a given moment, in the institution where the workshops take place, a general restitution of the work accomplished is presented to an outside audience (this happened at the CNSMDL at the end of two days of work, and at the Lyon II University also after two days of work). At the university, this restitution was followed by a concert by the Orchestre National Urbain.

The specific project linked to the Hors Norme Biennial took place at three different sites:

- September 15-16, 2023, at the Grandes Voisines, in Francheville near Lyon. This institution described itself on its website as “a social, interactive and solidarity-based place where you can sleep, eat, work, paint, discover an art exhibition, take part in a choir… and experience encounters.” (Les Grandes Voisines). This accommodation facility is a place where refugees can stay awaiting regularization. It’s this particular group of people that was targeted during these two days of practice.

- September 18-19, 2023, at the Lyon CNSMD, department of the music teachers training program [FEM: Formation à l’Enseignement de la Musique]. Two days of workshops designed as encounters through practices between the Conservatory students and the refugees staying at Grandes Voisines, with a public presentation of the work at the end of the second day.

- September 20-21, 2003, at University Lumière Lyon II, workshops with refugees, and students from the university and the conservatory (on a voluntary basis), with a public presentation of the work at the end of the second day, followed by a concert by the Orchestre National Urbain.

1.2 Period of Preparation of the Project

Joris Cintéro :

As I write these lines, I can’t quite remember clearly the circumstances in which I was first introduced to the device. All I remember is a few snippets of discussion with Karine Hahn describing a « project we’re involved in with the CRA.P », the first stage of which is taking place « in Francheville [a suburb of Lyon], in a refugee home center », and that « the students have been kept informed » for a long time. I have memories of the objectives that were set for students through an agencement like this, particularly at Grandes-Voisines.

I remember the objectives that were set for the students through such an agencement, particularly at Les Grandes-Voisines: meeting with an otherness that we assume is not common in the ordinary course of their work as teacher-musicians, creating musical moments designed to invite an audience unfamiliar with the traditions of so-called Western art music, adapting to circumstances that are hardly conducive to artistic education, and, of course, taking a step back from social and political issues involved in artistic education.

A few days before the first session at Les Grandes Voisines [GV], Karine reminded the students of the Education Department about the project. After a group discussion in class with the students, we asked them about the possibility of going to Les Grandes Voisines on Friday and/or Saturday. We realised that very few of them were available/motivated to come with us on those days. Only one first-year student (Grégoire) was available, whom we didn’t know very well at the time – the course had only been running for a week. Almost all of the other students told us that they were busy or that they would have liked to come but hadn’t received the information in time.

We also stressed the need for students wishing to come to bring instruments that could be handled by children – I remember awkwardly insisting on this, suggesting that it was only a question of working with children and that they would be particularly careless. The students’ answers led us to discover that very few of them had several musical instruments.

Part II : The Nomadic Collective Creation at the Grandes Voisines

2.1 Workshops at the Grandes Voisines

Joris Cintéro :

On Saturday September 16, 2023, after collecting an old classical guitar at home and Karine’s electric harp from Villeurbanne School of Music, we both drove to the Grandes Voisines, arriving mid-afternoon, around 3.30 pm. Karine parked in the entrance car park, a stone’s throw from a sort of faded (empty?) gatehouse used to monitor comings and goings at the home centre. It’s a bit far from where the workshops are taking place (it has to be said that the signage wasn’t very clear and there’s nothing on the outside to announce the Biennale Hors-Normes). After a short phone call, Giacomo beckoned us to approach from afar and welcomed us.

I meet the various members of the Orchestre National Urbain for the first time, as they emerge from a room housing various instruments. Giacomo takes us on a quick ‘critical’ tour of the premises. We discover a maze of rooms, doors and corridors, and are quickly briefed on the organization of the premises. Indeed, Giacomo is already familiar with the place (the Orchestre National Urbain has already been involved with the premises) and has experienced tensions with some of the people working there. During the visit, I quickly understand that there are communication difficulties between the different people involved (and their respective institutions) regarding the management of the site, and that some of the artists present at the Biennale Hors-Normes [BHN] are not ‘on the same wavelength’ as Giacomo.

I have the impression of a labyrinthine that struggles to hide the stigma of its former use (as a hospital for the elderly). Although some corridors are lined with paintings and works of art of all kinds, and some exterior points suggest artistic activity (sculptures etc.), the place exudes a certain coldness (neon lights, false ceilings, greyish paint, cracked tiles etc.) typical of administrative buildings, retirement homes or even hospitals. Some rooms appear a little gloomy and smell of damp – such as the concert hall on the building’s first floor, which stands in place of the building’s former chapel. To add to this impression, Giacomo will add during the visit that autopsy tables are still present in the building’s basements. In the distance, we see a soccer stadium, the use of which in a geriatric hospital is hard to understand, and posters showing an installation to be held there. I’m struck at this point by the ‘waltz’ of keys that accompanies this visit, a sensation probably due to Giacomo’s annoyance at the need to lock up behind oneself “just in case”, “because some refugees don’t hesitate to help themselves”, or because the equipment cannot be supervised in our absence (and that of the Orchestre National Urbain members running the workshops).

After a good fifteen minutes’ walk around the site to find out where the various workshops were taking place, we’re back to where we started, under the sort of Barnum where the Orchestre National Urbain team had welcomed us earlier. It was quite warm, and Grégoire, the only student from the CNSMDL that day, had just arrived.

Once the visit was over, in the middle of a sentence, Giacomo mentioned the major difficulty of the afternoon, which we soon noticed: no one had signed up to take part in the workshops. According to him, this was due to the fact that the social workers working at the venue had not passed on the information to the venue’s users (we didn’t see any posters during the visit and we met people working at the venue who weren’t aware that music workshops were being held), a lack of communication that could itself be explained by a falling out between the BHN’s project leaders and the venue’s organisation – the details of which we would later learn. So the day began without any children or adults, apart from Omet – a user of the venue who was not initially presented/categorised as a beneficiary of the project but rather as a full member of the activity.

In the absence of an audience, the members of the Orchestre National Urbain don’t give up and invite Karine, Grégoire, Omet and myself to start playing with them in the collective sound workshop.

2.2 The Collective Workshop « Sound Laboratory » at the Grandes Voisines

Joris Cintéro :

Giacomo presents a collective musical workshop similar to the group workshops later offered at the CNSMDL and the Lyon II “Lumière” University. It consists of a collective improvisation directed by a conductor, officiating only through a set of coloured cards indicating particular musical intentions to guide the improvising group.

The instruments are as follow:

– ‘Urban lutherie’ instruments : Spicaphone / Mirror-Harp [amplified]

– Electronic Instruments: (Korg monotribe/Kaosspad/Roland SP 404SX/MicroKorg)

– Effect pedals (Whammy with Spicaphone)

– Microphone [amplified]

– Acoustic instruments (Snare drum, electric guitar, “Chinese chopsticks” as drumsticks)

The console and the various cables used to amplify the instruments are not used as playing aids in the system.

The set of cards includes 7 colours associated with the conventions already mentioned above: In addition to this ‘colour coding’, the sound volume of the improvising group can be varied by means of a signal.

On this day, the instruments are arranged around the conductor (he or she). The workshop took place in a large room with green linoleum and several bay windows (some blacked out with curtains), giving direct access to the outside – allowing passers-by to see (and incidentally hear) what was going on. Although it is not, so to speak, central to the architecture of the home centre, this room is nevertheless in the path of pedestrians and cars and overlooks several other buildings – which will be important for the rest of the day.

The workshop began with an explanation from Giacomo, who presented the various aspects, emphasising the colour codes and the objectives (working on the sound, freeing up any inhibitions, creating a space of equality between musicians and non-musicians, etc.). As I was involved throughout, I don’t know exactly how long each improvisation lasted. The only thing I do know is that the improvisation rounds stopped once everyone had conducted at least once – some repeating the exercise several times.

The workshop begins. Everyone seemed to enjoy playing the game. The comments made by those attending related mainly to the difficulty of remembering in the moment the conventions associated with the coloured cards (I had to wait until the 4th or 5th round to align myself ‘correctly’ with the cards), the nuances suggested by the conductor and the pleasure of playing on ‘exotic’ instruments (the mirror harp and the spicaphone in particular). Almost every workshop ‘round’ ended with a discussion of what had just taken place, mainly on musical issues (the conductor’s intention, nuances, etc.). The first few workshops went ‘very well’ insofar as it seemed to me that most of the participants were used to the exercise.

During the improvisations, we can see some groups of adults, children and parents, sometimes passing by, some discreetly approaching the auditorium – most pretending not to be seen. It was amid this flow of passers-by that a man in his early forties joined us, accompanied by his 5-year-old daughter. Rather reserved, he said from the start that he had come ‘for his daughter’, who seemed particularly happy and cheerful when the members of the Orchestre National Urbain invited her to join in the collective improvisation. The child took part in several ‘rounds’ of the workshop accompanied by various participants (who sat her on a chair so that she could play on the Microkorg, for example, or reframed her game in relation to the coloured cards) and the father took on the role of leader once – as well as taking part in a few rounds of the workshop himself. Initially reluctant to take part (he was only going to watch his daughter), he joined us at Giacomo’s request and gradually ‘relaxed’, without showing however any sign of letting go (which I interpreted as the fact that the participants were fully committed to the game and were sometimes overwhelmed by it). Both left the room after several rounds of workshops, clearly happy to have been there.

Once the auditorium was closed, we moved on to the adjacent room, where a cello improvisation and painting workshop was being held.

2.3 Cello/Painting Workshop at the Grandes Voisines

Karine Hahn, Lyon CNSMD, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (11’19”- 11’44”)

Joris Cintéro :

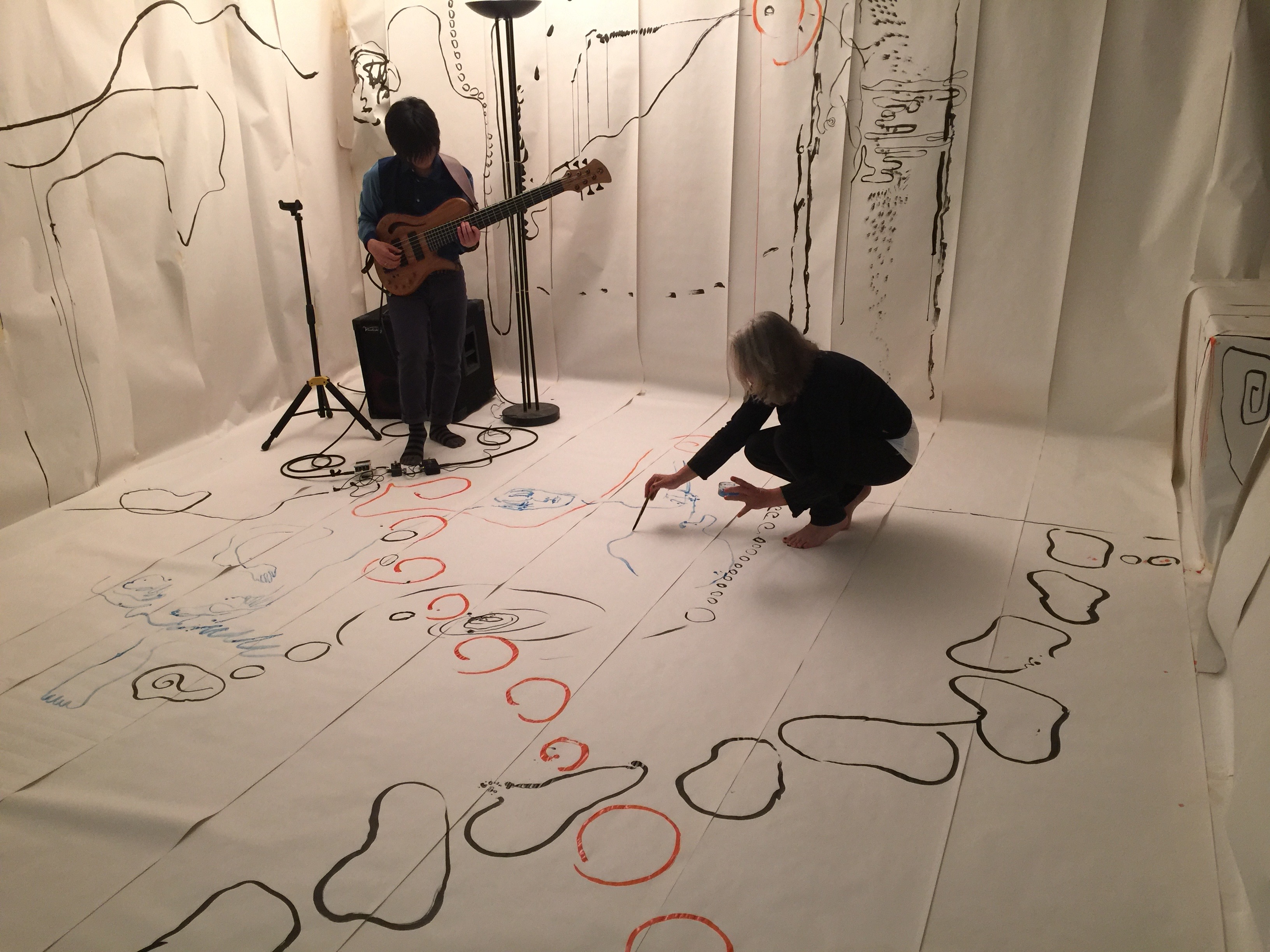

The cello-painting workshop was run by Selim Penaranda (cello) and a person (painting) whose name I have forgotten (I would later learn that she was replacing Guy Dallevet, who was absent that day). It takes place in a room that is large but rather cluttered with cardboard boxes, paintings, sculptures and various objects.

The workshop was organized quite simply. On one side we have Selim with 3 cellos (1 acoustic and two amplified electric) and on the other the painter with a set of sheets of paper, acrylic paint, cardboard boxes to spread it out on and protective clothing that is visibly worn – the room seems to be used very often for activities of this kind, as can be seen from the numerous paintings on the walls and the paint stains in the sink. In the same spirit as the productions that would follow for the rest of the week, this agencement involved interaction between the groups who were painting and the groups who were playing the cello. The workshop ends with individual cello improvisations based on a support painted by the performer.

Lucien 16’s (Sébastien Leborgne) on the relationships between music and painting, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (3’48”-4’48”)

The cello activity led by Selim is always organised in the same way.

1. Presentation of the instrument and the agencement.

2. Experimenting with the instrument.

3. Directed improvisation with color code. This activity requires at least two people

to play (sometimes including Selim) and one to conduct.

Selim first introduces the cello by playing a few notes and repeatedly stressing that there is no one right position for playing it, that the most important thing is to feel at ease while playing. In this sense, he does not hesitate to show positions that could be described as heterodox in relation to the common representation of cello playing, which is associated with a so-called ‘classical’ position (the instrument is held between the legs, the feet on the ground, the neck of the instrument resting on the shoulder). He deliberately places his feet on the edges of the cello, showing that it is possible to play it in this way. The same goes for the bow, which he suggests holding in several different ways, emphasizing, as he would later do at the CNSMDL, that “it can be held like a doorknob”. He did not, however, prevent participants from holding the instrument and the bow in the ‘conventional’ way. Once this introductory ‘ritual’ has been completed, he lets the participants explore on the cello while introducing the rest of the workshop, which consists of an improvisation with another participant.

The person ‘conducting’ during the workshop changes as the workshop progresses. The code used is the same as in the previous workshop.

On the other side of the studio, the painting is organised in an equally recurring fashion. The supervisor presents the task at hand, i.e. to paint a canvas while soaking up the sounds created by the cellists, using a piece of cardboard to create, as the supervisor shows, multi-colored circular shapes. Basically, you pour a few drops of paint (one or more colors) onto the canvas and use the cardboard support to spread the paint over a sheet of paper, creating spirals of some kind.

The link between the two parts of the workshop doesn’t seem to be obvious to everyone, as evidenced by the fact that during a break in the cello when I was looking at the other part of the studio, some of the painters paid no attention to the music (which isn’t always true, since overly long silences sometimes lead painters to grumble gently about the absence of music for painting). I take a few photos of the studio.

The workshop ends with a series of individual improvisations on the cello, based on a visual support, i.e. the painting created earlier in the workshop. None of the local residents will be joining us during the workshop. We decided to take a break after a short hour of collective work.

Cello and painting workshop at the Grandes Voisines, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (5’45”-12’28”)

2.4 Trombone Workshop at the Grandes Voisines

Joris Cintéro :

The break offers an opportunity for some of us to light up a cigarette, drink a little water and have a general discussion about the facilities on offer and the lack of an audience. Although the atmosphere is very friendly, I can still feel some disappointment among some Orchestre National Urbain members. I also said to myself at the time that mobilizing so many people over two days for such a small audience was a considerable waste of time and money. We talked a bit about the venue, its shortcomings (the inhabitants are said to be housed by ‘ethnic group’) and the fact that, apart from its inhospitable aesthetic, they don’t seem to be all that badly received. Mention was made of the existence of a building dedicated to single women, a group that, according to Giacomo, is difficult to invite to activities because they have been through traumatic migratory experiences. Everyone had their own little anecdote, especially those who already knew the place.

As the afternoon wore on, Odenson Laurent, a young member of the Orchestre National Urbain, played a few notes on his trombone. These notes had the effect of a call. Several children approached us, shyly at first and then more directly. They want to play and let us know. Giacomo and Sébastien rush to retrieve the trombones they had stored in a room in the building. The scene gives the impression that we’ve been taken by surprise, that the ‘public’ is finally pouring in, and that we mustn’t miss the boat.

The trombone cases arrive and are hastily placed on the floor. It’s an interesting moment in that we all (the participants from the previous workshops) gradually begin to ‘frame’ the workshop as it takes shape. Here we disinfect the trombone mouthpieces with alcohol, there we show a child how to grab and hold a trombone, and next door we keep those waiting for their turn.

Trombone workshop at the Grandes Voisines, extract from video « Biennale Hors Normes » (0’23”-0’56”)

Odenson took control of the workshop, spoke loudly (it had to be said that the children were numerous and in a hurry to play) and showed them how to blow into the mouthpiece of the trombone. Most of the children succeed. He suggested a series of exercises/games where the first thing to do was to blow hard once. The children did this successfully, laughing and trying again without waiting for Odenson’s invitation. The volume increased rapidly, and the children seemed to enjoy the activity. Odenson then suggested playing with the slide. Some of the children dropped the slide (it must be said that in some cases the trombones were as big as those playing them), which led to laughter from the others and impatience from those waiting their turn – some then came to the aid of their friends by holding the slide. The children clearly seem very happy with the experience they have just had. New faces appear: several women start to arrive, some leaning over the balconies to see what’s going on.

Same again, the mouthpieces are cleaned, the children are given a few pointers on how to hold the trombone (each one offers a bit of advice), those who will be coming next are made to wait, and the women who have just arrived are invited to try out the experiment. Karine, for example, was asked to convince a local woman to join in the exercise, which she managed to do.

It’s interesting to note that although, apart from Odenson, no one ‘plays’ the trombone (or at least no one categorizes themselves as a ‘trombonist’), everyone takes the liberty of showing the children how to blow into the mouthpiece, how to make the lip movement that allows them to do so, or how to hold the instrument – for example in the interval to those who are waiting or directly to those who are taking part in the workshop.

After several rounds, the workshop stops, and the Orchestre National Urbain members talk to the women and children present to tell them about the next day and the continuation of the workshops.

Photos of Grandes Voisines, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (2’37”-3’33”)

Part III : The Project at the Lyon CNSMD

3.1 Meetings during the Project

Jean-Charles François :

The staff of the Orchestre National Urbain usually meets in the morning before the start of the workshops in order to (re-)define the content of the day, taking into account precedent actions.

Giacomo Spica Capobianco and Sébastien Leborgne :

First phase, “Team meeting”:

The artistic director (Giacomo Spica Capobianco) reviews the current project with all the artists working with the Orchestre National Urbain. These meetings are an opportunity to evaluate the workshops as a group, in order to ensure that the project continues to evolve. These moments of discussion allow exchange on evolutions, constraints and difficulties encountered.

Preliminary to a program proposition for the day, a discussion takes place to enable us to adapt to situations encountered on a day-to-day basis.

Second phase: “Meeting of the team with workshop participants”:

Each morning, a time is scheduled for discussion with all workshop participants.

Obviously, this moment is important, given that no prior selection level is required, both technically and socially, the participants are expected to work collectively.

It’s important that the ones go towards the others for a more constructive encounter leading to elaborating an improbable creation.

The point is to convey to participants that they are at the service of the project within a collective creation.

All the workshops are filmed.

It’s important to have a video support of each workshop so that all members of the Orchestre national Urbain team can discover each other’s work. This allows the project to evolve.

Jean-Charles François :

For example, here’s the description of such a meeting, which took place on the second day of workshops at the CNSMDL, the morning of September 19, 2023. This meeting brought together the Orchestre National Urbain team, and the CNSMDL-FEM team.

Giacomo Spica Capobianco reports on problems encountered at the Grandes Voisines. The venue of the Orchestre National Urbain had not been properly prepared by the supervising staff of the center. It seems that no information reached the intended public, therefore it was necessary for the members of the orchestra to start playing in the courtyard, to welcome the people passing by and invite them to participate. During this process, it was mainly children and mothers of these children who participated. As a result, only one refugee was allowed to come to encounter the CNSMD students. Giacomo sums up the objectives of the day, which are to give the students the opportunity to take charge on their own with working elements that are new to them. This is why they are not allowed to use their own instruments. For Giacomo, we’re not there to dictate behavior, but to create situations of collegial research with a view to projecting ourselves in practices accessible to any audience.

3.2 The « Sound Laboratory » Workshop at the CNSMDLL

Jean-Charles François :

The morning session (September 19) takes place in a large chamber music space with a stage. The stage is organized with a series of instrumental stations (standard instruments, simply built instruments, electronic instruments, amplified voice) as described above. A floor space outside the stage is devoted to dance. Students are divided into three groups. The people who don’t participate in the performance of a group, are sitting on the floor or on chairs outside the two performance spaces.

The session starts with a 10-minute body warm-up led by Sabrina Boukhenous. She is a member of the Orchestre National Urbain, an actress, stage director, and sound and lighting technician. Her role in the Orchestre is to take charge of body movement and spoken word. The warm-up takes place for everyone in an atmosphere of good humor and pleasure of doing: rubbing hands, breathing exercises, activating different parts of the body, jumping, etc.

Concerning Sabrina Boukhenous’s “Body and movements” workshops, here is an extract taken during a similar project of the Orchestre National Urbain that took place at the University Lyon III in 2024: valid.

Sound Laboratory at the CNSMDL, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (17’25”-18’42”)

One of the specific aspects of the setup is the presence of texts written during the workshops and read aloud by each student through a microphone placed on stage. According to the instructions given by Giacomo, the voice doesn’t have to follow the color codes, but unfolds its flow as a solo, according to the choice made by the person who speaks. The main difficulty is for the audience to be able to hear the spoken voice clearly, whether the protagonists are unfamiliar with the microphone, lack confidence or energy, or whether the sound level of the ensemble is too loud, since looking at the color-coded cards may not allow immediate listening of what others are doing. Giacomo, fairly early during the session, demonstrated with the microphone how the voice can be used more effectively. During the performance period of the third group, at one point, it was decided not to use the code-colored cards, but to rely solely on the solo voice with the need to be able to understand the text: the voice here replaces the conductor. After trying out this idea, a short discussion took place on improvisation notions: the necessity of listening to others, the question of reacting to ongoing energies and to other proposals, the idea to let others be at the forefront, especially in the case of the presence of a text. At the end of this first part of the morning, a situation was experimented with involving three vocalists reading their text.

The presence of texts, several times (notably on the part of Giacomo), raised the question of physical commitment and the meaning you have to convey reading the text. Of course, it’s difficult to make an immediate engagement in an activity you’re doing for the first time, when you don’t know where it’s going to lead. But the difficulty of commitment on the part of the students also stems from the fact that they don’t automatically (yet) subscribe to something too far removed from the aesthetic values that are promoted on a daily basis at the conservatory. The behaviors induced by European high art music written on scores imply on the one hand, a deep commitment on the part of the composers in their aesthetic projects, and on the other hand, an assumed detachment on the part of the performers who should be ready to play a diversity of aesthetics. We could say that, in this context, the performer’s engagement is only manifest when playing in public, in an attitude close to the theatre actor where the proper commitment is “played”. In this context, you are not accustomed to throwing yourselves heart and soul into any type of activity, without taking time to reflect on the matter, the aesthetic content is therefore not a commitment but a play. The commitment of the performers of the so-called “classical” sector is turned above all towards the manner in which to approach sound production, and in this way their principal identity is focused on their own instrument or voice. The body of the Western human being tends to be disconnected from meaning, having to construct meaning according to contexts, with the risk therefore of missing out on a more fundamental state in which the body assumes and believes in its own production of meaning. As it happens, there exist a great deal of musical (and dance) practices where the performers’ commitment is not separated from conditions of production, and where meaning is fundamental from the outset, that is at every level of ability. This is particularly the case with the musical practices of the Orchestre National Urbain and within the actions that it carries out in underprivileged neighborhoods.

Some students have decided to be present at the sessions, but not to take part in the proposed practices, and to be there as observers. This is a tiny minority, 2 or 3 among the 50 or so persons present. Giacomo had made it clear that this attitude was possible, that there was no obligation to participate in the action. Yet, one of them decided suddenly to join the active group, when improvisations without conductor and coded colors were tried, with the text or the dance now being the elements to be followed. He took the electric guitar (that was set-up horizontally), tuned it in the standard way, and played it with the usual guitar-playing position.

For dance, the term of “body movements” is often used to emphasize that on the one hand, these are free movements in space, and, on the other hand, that there is no artistic ambition with technical implications that could prevent the immediate participation of any person present. At the beginning of the group 1 performance, there is no dance, then gradually it takes greater importance. It soon became clear that the conductor needed to see the dance (as well as listen to the instruments) to influence the decisions on color changes. With group 3 (after the experimentation to follow the text) it was decided that the musicians should be influenced by the dance rather than following the color codes. As in the case of the text, this trial provoked a discussion on the relationships between dance and music, raising questions on mirror imitation, on the conditions for the musicians to follow collectively the dance, on the risk of one artistic domain dominating another, and on the need for communication to circulate. An idea is proposed: an improvisation in which all these working axes are mingled.

Concerning the presence of a conductor with the color-coded cards, the reality of actual practice raises a number of questions. One important aspect is that, for each new sequence of play, there is a new conductor, therefore there is no danger of developing conducting “specialists”, and there is a democratic distribution of the different roles. But it is precisely this particular set-up that tends to reinforce the general representation that the people present have of the dominating power of the orchestra conductor. Therefore, those who assume this role have a tendency to over-invest the power that is given to them: it’s not just a question of showing color-coded cards, and indicating loudness levels, but it involves exaggerated body attitudes to pass on information to the instrumentalists to ensure that they are respected, and we soon find ourselves in a situation similar to “sound painting”. This over-investment on and of the conductor results in the domination of the eye over the ear: having to look constantly at the conductor prevents the focus on listening to both one’s own sound production and that of the others.

The oral-written duality is a very important element at play in the context of the CNSMD and the musical forms that define its contours. But what is at stake in this context is very different when it comes to immediate access to musical artistic practices for anyone (whatever their skill level and social background). In this case, very precise mechanisms need to be invented in order to achieve convincing results. Towards the end of the first part of the morning, Giacomo reminded us of the pedagogical nature of the work in progress: the difficulty lies in doing things in depressed cultural contexts or when people of different cultures meet. How to build activities that from the beginning offer the possibility of confronting fundamental issues, but in an accessible manner, to allow people to construct their own meaningful situations. Accessing active participation comes first at the outset and takes precedence over any consideration of artistic quality or of standardized behavior. The coded-color cards and the presence of a conductor that manipulate them to give form to the performance ensure in all contexts a rapid access to an effective practice, in which the artistic stakes are not at all resolved yet are already inscribed in the content of the action.

3.3 The Human Beat-Box Workshop

Joris Cintéro :

The day of September 16 (at the Grades Voisines) ends with the workshop led by Sebastien Leborgne (Lucien 16), which focuses on « Human Beatbox ». Sébastien is a member of the Orchestre National Urbain, and a rap, spoken word artist.

The workshop takes place in a room inside the building. The room is particularly small and is in the passageway of a corridor, opposite several lifts: there is quite a bit of traffic.

The workshop requires very little equipment: a few sheets of paper, a console, a looper, a microphone and a loudspeaker to amplify it all.

Sébastien describes his workshop. He begins by explaining the principle of Human Beatbox. To do this, he draws several instruments on a sheet of paper. We see a bass drum, a snare drum and a hi-hat cymbal. He directly demonstrates the sound that can be associated with each of the elements drawn on the sheet. He then puts his words into practice by recording a beatbox loop.

He then asked the workshop participants (who were mainly members of the Orchestre National Urbain and the CNSMDL) to make a loop themselves. During the workshops, a group of 3 children stopped to listen to what was going on. Sébastien invites them to give it a try themselves producing a loop with the looper. The children laughed, seemed embarrassed, but went ahead nonetheless. He took the opportunity to ask them if they were available the next day to take part in the workshop. This workshop took place in a particularly limited amount of time compared to the preceding ones. It shows the versatility of the system put together by the members of the Orchestre National Urbain – as well as explicitly the difficulties to which the collective have to face on a regular basis.

Jean-Charles François :

During the second part of the morning of September 19 (at the CNSMDL), I attended a “Human Beatbox” workshop led by Sébastien Leborgne (Lucien 16’s).

The technical set-up of the CNSMD studio consists of a microphone to amplify the soloist’s voice, with a sampling machine for making loops of vocal sounds, to create repetitive rhythms with the possibility of superimposing vocal sound samples. Several microphones are available to record several voices at the same time.

The introduction by Sébastien defines the context of rhythm production through vocal imitation of drum set sounds (beat box) over which a text can be spoken.

The first experimentation concerns the imitation of bass drum sounds, of charley, of snare drum with the voice, and to record them to form a loop. A loop is created over which the participants can add another vocal production to form a new composite loop.

The following situation, as defined by Sébastien, involves a) creating a rhythmic loop with 4 vocalists; b) then the soloist places the text on this rhythmic structure. Sébastien says that the students should do this task in their own autonomous way, he is only there to answer questions they might have. Creating the loop is quite easy, without much time at hand to try several examples. Adding a text to the invented loop poses more of a problem, as the participants read their text without any rhythmic inflections, independent of the content of the rhythmic loop. Sébastien suggests that the loop accompanying the Human Beat box should fit the text and not the other way round: “since this text is a dream,” the loop should reflect this mood.

A new attempt to create a beat box loop with five superimposed voices is made. A student speaks her text over the loop. She tries to connect her text to the rhythm character of the beat box. Sébastien remarks that what is principally at stake is not for the spoken voice to correspond to the rhythm of the loop, but to “impose yourself on the rhythm of the loop”. The spoken word doesn’t have to comply with the basic rhythm but should be guided by the right and true emotion. The student tries again to read her text over the loop but stops fairly quickly.

Someone asks if it’s possible to sing the text. Sébastien answers: “you can do what you want.” A student tries then to speak her text and to sing part of it.

Observing this workshop, it appears clearly that the main challenge that the students of the CNSMD have to face in this project lies in this very new activity for them of having to write a text and, above all, speak it with a rhythmic accompaniment.

Human beat box workshop at the CNSMDL, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (13’25”-14’29”)

3.4 Public Presentation of the Work in the Conservatorium Courtyard.

Jean-Charles François :

In the afternoon of September 19, a public presentation of what had been done in the workshops was proposed to the CNSMD community at large in the courtyard next to the main concert hall. An amplification system had been installed and the space was organized in the same way as in the Chamber Music space, a combination of instruments grouped around a solo voice, a space for the dance, and the paintings exhibited on the floor. The public (sparse, apart from the participants themselves) was sitting on the steps leading to the concert hall building.

The three groups of the workshops present performances in which there are musicians and dancers, often with a change of role in the middle. In the attitude of the performers, there’s a compensatory effect, since the production, still too experimental doesn’t correspond to the criteria of artistic excellence prevailing at the CNSMD. Seemingly, they have to show, a) the pleasure of doing an unconventional activity; b) stressing the energetic aspect of the experience; c) showing that it’s an entertainment situation in which one can be content to be only half committed; and d) sometimes bringing out the ironic character in relation to an uncomfortable situation. However, there is no aggressivity in these attitudes towards what has been proposed, but rather a problem of positioning towards the community in which the public presentation is offered.

In Group 2, a conductor, very much like a “composer”, develops a form that stages elements in a sort of narrative that allows the text to emerge. Thanks to this “in house” know-how, we’re closer to what might eventually be accepted by the institution as artistically valid.

Public presentation in the CNSMDL courtyard, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (20’35”-22’46”)

At one point during the performance, a CNSMD professor came in the courtyard to demonstrate her vehement disagreement with what was going on, and in particular with the sound level of the amplification, which prevented her from teaching.

Outside the FEM staff who are partners of the project, no representatives of the CNSMD directorate were present during this presentation. Yet, the director is very much in favor of the development of this type of project.

3.5 Reviewing the project on October 10, 2023 at the Lyon CNSMD

Jean-Charles François :

A debriefing day of the project was organized at the Lyon CNSMD with the teachers and the FEM students.

A) Debriefing meeting with the leaders of the Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p and the FEM staff.

et du CNSMD de Lyon

The morning started with a meeting of the Cra.p and CNSMD staff, during which the students met separately in small groups of 4 or 5 to prepare what they wanted to convey at the general assessment session that followed. Present at the staff meeting: for the Cra.p, Giacomo Spica Capobianco and Sébastien Leborgne; for the FEM (CNSMDL), Karine Hahn, Joris Cintero and Guillaume Le Dréau; and myself, Jean-Charles François as an outside observer.

Here are some of the ideas expressed at the meeting:

- What are the formative aspects for the students and through what issues?

- What is at stake in this project?

- Thinking about the aftermath of the project: other types of collaborations between the orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p and the FEM?

The students had to confront musical issues in a practical way, thought out in continuity with social and political contexts. They had to manipulate and fabricate sounds in transversal and transdisciplinary situations, that is confront unknown musical materials, consider practices involving simultaneously several artistic domains, and encounter cultures different from their social and artistic environment. Their aesthetic concepts were challenged by these various approaches. The pedagogical aspects of the project emphasized experimentation with musical practices open to all whatever their skill level, and on inventing ways designed to encounter otherness. The two essential questions were: how to make music together with any public? And what is exactly involved in developing projects in specific places and circumstances?

Two critical reflections emerge during the meeting:

- The problem of the plethora of labels prevalent in each cultural milieu, which classify any practices once and for all, either to acclaim them, or more often to consider them as unworthy of interest, or else to rationalize them in order to better control them in the dominant order of things. How in transversal and trans-aesthetics encounters can we envision situations in which a certain indeterminacy of materials will enable new aesthetic grounds to emerge, common to the diversities present?

- The problem of intellectual and artistic tourism is prevalent today in many higher education programs in the name of access to the world’s diversity. Experiences giving access to this diversity are multiplying in study programs with not enough time at hand to go in-depth into each of them. Cultural enrichment often goes hand in hand with a misunderstanding of the major issues at stake in the various practices. How within the limited time allotted to face this difficulty?

The Orchestre National Urbain offers the permanent possibility for anyone to follow a “tutoring program”, open to particular requests for training and project development.

B) Assessment with the CNSMD students

Each group of students presents their conclusions in turn. The group of students who also attended the Lyon II University sessions will speak last. In general, the feedback is for a large majority very positive: the artistic, social, and political objectives of this kind of action are well understood and the practices have been experienced in meaningful ways. Here are the different elements that were expressed:

- The idea of desacralizing the musical instrument. The instrument is no longer considered as a specialized entity, but rather as an object like any other capable of producing sounds. The fact that everyone has immediate access to sound production means that all the issues at stake in musical practice can be put into practice, whether in terms of technical modes of production or of artistic issues. The need to make music with materials that are not mastered at first, enables one to break away from the logic of expertise and puts all participants at the same level of competency. For one of the students, this approach is close to the Art Brut and Fluxus. This should enable effective encounters between participants of different cultural backgrounds. The tinkered instruments (or tinkering instruments) opens up a different way of considering sound matter, timbre, and the use of sounds generally considered as outside the musical realm.

- The declamation of a text accompanied by instruments. This aspect is certainly the most difficult to achieve for specialists of instrumental music. The “Human Beatbox” workshop was experienced as the activity that best opened the way to inventing sound materials through the realization of simple rhythms.

- Improvisation stemming from guidelines easy to follow. This is what makes it possible to become master of one’s own production. It’s an effective way to approach improvisation in an uninhibited manner. It opens the way to a dynamic of immediate sound production separated from preoccupations with playing only what is completely mastered.

- The realm of amplification is what the CNSMDL students are least familiar with. This first approach is much appreciated.

- The role of conductor: you have to dare to assume this role in order to control the general form of an improvisation, from the perspective of building an instant composition. For some students the presence of a conductor is an obstacle to improvisation, which implies individual responsibility and requires a less urgent temporality for dialogs to take place, without relying on the authority of a conductor.

- The idea of doing things immediately before any reflection is an important element of the practices proposed. There’s an urgency to do things without asking questions, to do what is not yet mastered before considering the means to achieve it.

- An important aspect of the project is to encourage audience participation, as happened at the end of the concert by the Orchestre National Urbain when everyone started dancing in the University amphitheater.

Among the problems raised by the project, some students noted a time organization that sometimes seemed too slow, and at other times too short. Boredom or frustration are at the root of a certain fatigue. There is a concern about the notion of “work”, induced by the immediacy of doing, which may imply a strong devaluation of the notion of art. One of the students expressed her frustration at the excessive amplification levels and absence of consonant sounds, which made her very tired. Several people noted the absence of relationships between the painting workshop and the musical ones.

The issue of the public presentation of the work in the Conservatory courtyard was the subject of a lively debate. The situation ran completely counter to the dominant culture of an institution requiring a high level of excellence in any performance. In addition, the public presentation used means of musical production rarely in use in the institution, in an undefined style in relation to the prevailing contexts. The amplification levels made it impossible to ignore this event in every corner of the Conservatory. The students were therefore obliged to do something that was in direct conflict with the surrounding community and that put them at risk of being disqualified. Many wondered whether this idea of presentation of the work was really necessary to the overall conduct of the project. The students had to face numerous ironic comments from their colleagues present at the performance. One particular phrase stuck out: “the slobs in the courtyard!” Other expletives were used, such as “degenerates” with more disturbing historical connotations. Perhaps the audience needed to be better informed about the situation and its pedagogical context before the event.

Joris Cintéro, Lyon CNSMD, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (22’50”-23’44”)

In the answers to this debate by the members of the project teaching team, the need to make public an activity that is unusual in Conservatory practices remains of great importance. It’s not just a general question that could be swept under the carpet of anonymity, but something that needs to be put “on the table” of today’s reflections on art and its transmission to all.

For Giacomo the public performance at the CNSMDL was not initially planned, but the impossibility of having all the students present at the Lyon II University for the general public performance of the project changed the situation. He understands the frustration of people present concerning “art”, but the issue should be shifted to the legitimacy of the proposed activities. For him, the issue is how music teaching institutions are going to put in place some mechanisms to open up their activities to people who have no access to practices. He points out that the most obvious problem in his work with the various institutions in which he develops his projects, is the often negative attitude of the leadership staff, teachers, animators, social workers, and so on. They defend their territory, and often feel that those under their authority must conform to their own way of thinking. If they are not directly involved in the project, its course is seriously jeopardized. Effective knowledge of a project by the host institution as a whole is an essential element in getting the idea off the ground.

When the cultural animators are favorably inclined towards the Orchestre National Urbain’s projects, things happen in a very positive way. Here is an example of a commentary by Khadra Hamyani, an educational helper at the “Forum Réfugié”, during another project developed by Cra.p at the Lyon III University in 2024, involving young refugees, « From Body to Movements, From Gesture to Sounds”:

Khadra Hamyani, extract from video « Du corps aux mots, du geste aux sons » (2’37”-5’34”).

Karine Hahn reminds the students that on the one hand, Giacomo came one year before to present the details of his project, its outlines and challenges, and on the other hand, a text of presentation of the project and its objectives was distributed to all shortly before its realization. In a context where often the people involved don’t have the same understanding of the terms of a project or may even understand exactly the opposite of what is proposed, any mediation seems of little use in avoiding conflictual expression. What counts however is the affirmation of legitimacy through action.

Joris Cintero underlines the difficulty that the institutions have in using surveys to question their own ways of operating, especially on the subject of recruitment of people present. The last formal enquiry on the social makeup of the student population at the Lyon CNSMD was done in 1983, [1] it showed that only 1% of farmers’ children were present, and only 2.8% of blue collar workers’ chidren, and so on.

The issue of the public performance stems from the various difficulties encountered with the general administration of the institutions and the people who work in them. One student who was present at the Lyon II University noted that, at the beginning of the first day, no one was present ready to work with the Orchestre National Urbain, no advertisement had been made by the host institution, no support provided. Immense efforts had to be done to get 5 people willing to get involved. For Giacomo, the resistance of the University towards this project is obvious, there are no professors involved, nothing had been done to facilitate things. The feeling is that because it didn’t cost any money, it would have to fall apart. At the end of the first day, the question arose as to whether to continue on the following day. The answer is definitely that you have to keep going, you have to persist and play with the situation. For Joris 5 or 6 participants out of 29500 students, it’s a long way to go in the cultural domain.

Sébastien Leborgne describes in detail what happened at the Grandes Voisines, with the presence of 415 refugees accommodated, many of them women and children. Karine describes the start-up at the Grande Voisines: everything is ready to go at 10 in the morning, the technical setup is in place, the teaching team is ready to work, but nobody is there to participate. But this preparation is a guarantee to be taken seriously, the team is there in front of no one, with the same seriousness as if there were people present. Little by little people pass nearby, it’s on the move, it exists, it works no matter what.

At a certain point in the afternoon, a 11-minute video shows in fragmented form what happened at the Grandes Voisines. One of the most striking segments is a trombone quartet made up of three children and a mother, all playing together accompanied by body movements of great collective coherence.

In the diverse answers to the students’ preoccupations by the teaching staff, the following could be noted:

- Concerning the question of the need to do things in an immediate manner at the cost of quality control, Giacomo points out that most of the time, the projects he leads in different contexts take place within very limited timeframes, the passage of the group is often ephemeral. Here, doing must absolutely precede theory.

- The question of long-time involvement is addressed by emphasizing the role of Cra.p as a center of practices, as a place for continuing education, with also the objective to allow people living in deprived neighborhoods to access higher education degree programs.

- The choice of instruments works on two levels: on the one hand, you have to enable a first practical approach to playing instruments well-known to require years of work; playing trombone or cello immediately can arouse the desire to learn to play these instruments seriously. On the other hand, you have also to give access to sound materials that are easy to handle at first. Giacomo gives the example of the six-string electric guitar that requires demonstrating how to play it, whereas the “spicaphone”, an instrument he built with just a single string gives a more immediate access to actual practice.

On the subject of the access for all to musical practices, Giacomo tells of a story of a mother, following a performance given by her son, who is crying while saying: “I didn’t know that my son could have the right to make music.” In many quarters, people think that the access to musical practices is completely forbidden to them. The issue of cultural rights is essential. Karine remarks on the lack of places open to practices: where are the spaces existing outside the limited access specialized “schools”? Outside the Cra.p, there’s a crucial lack.

Photos of the project at the CNSMDL, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (13’08-13’56”)

Part IV : The Projet at Lyon II « Lumière » University

4.1 Morning of September 21 at the University “Lumière”, Lyon II

Jean-Charles François :

The morning session of September 21, 2023, takes place at the University “Lumière”, Lyon II (on the banks of the Rhône), in the space where art works are exhibited as part of the Hors Norme Biennial, and in the large amphitheater.

Given the difficulties encountered at the Grandes Voisines, at the last minute 20 teenage refugees (all male) of the “Centre d’hébergement” of the Lyon 1st arrondissement were able to come and to take part in this morning session and to the next day’s public presentation at the end of the afternoon. They could only be there during the morning of September 21 for one hour and a half (10:00-11:30 am) because of the Center’s that housed them strict rules on meals. Four students from the CNSMD were present on a voluntary basis. Lyon II University students, and visitors to the BHN exhibition could take part in the workshops, but this was a very marginal phenomenon. Giacomo told me what had happened on the previous day (September 20) when a small number of students of the Lyon II University participated in the workshops as they passed through the exhibition hall. This happened although no advertisement of the event had been provided by the University towards the student population. Their participation depended only on their passing through the space where the activity took place, and their eventual interest in what was being proposed.

This is a frequent aspect of the actions carried out by Giacomo and the Orchestre National Urbain: although they are often officially invited to develop their projects in an institution, obstacles are bound to arise on the part of the staff of the institution. The reasons for this lack of cooperation can be found either because what is proposed encroaches on established prerogatives, or the presence of people from outside the institution (or its usual audience) is not viewed favorably. In all cases, the attitude of the Orchestre National Urbain is to settle into a given space, and to raise the interest of persons lingering there or passing by.

Here are some comments from a Lyon CNSMD student who participated to a similar project by the Orchestre National Urbain at Lyon III University in 2024, “From Body to Movements, From Gesture to Sounds”:

Marie Le Guern, FEM student at the Lyon CNSMD, extract from video “Du corps aux mouvements, du geste aux sons” (8’47”-9’07”)

4.2 The Workshops in Lyon II University

Jean-Charles François:

Given the limited time available due to the presence of the young refugees, the organization of the workshops was limited to 15 minutes. This allowed 5 groups to participate in 5 workshops one after another, followed by a session regrouping all five groups for 15 minutes in the large amphitheater. This schedule was not completely realized within the allotted time, with each group actually taking part in only 4 workshops (out of the 6 proposed) before the session in the amphitheater.

The proposed 6 workshops were (as in the CNSMD):

a. Dance.

b. Cello.

c. Trombone.

d. Human beatbox.

e. MAO.

f. Sound laboratory

g. Painting.

Workshops at Lyon II University (MAO, Human beat box, cello, trombone), extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (23’58”-26’10”)

The workshops were held in the large exhibition space of the Hors Norme Biennial, and in two adjacent rooms. The principles were exactly the same as the ones described above, with immediate practice on sound materials, and the use of colored-code cards. The situations were the same as in the CNSMD, so, there’s no need to describe them in detail.

Because of the limited time, and the imbalance in numbers between the refugees and the other participants, few interactions between the different group members could really take place during that morning. Some of the groups were made up entirely of members from the refugee group. In the case of the painting workshop, I observed a situation with two large sheets of paper side by side, on which two completely separate groups were drawing: the first group was made up solely of black African male refugees, the second one only of white French female students.

The limited availability of the refugee group meant that the morning had to be focused primarily on welcoming them and organizing their activities, while the other participants had other opportunities to take part in all the workshops and performing situations. From this point of view, what was proposed to this particular audience was extremely successful: the refugees demonstrated a total commitment of their energy in the proposed practices and showed great interest in all the various aspects of the workshops. One of the strengths of the Orchestre National Urbain/Cra.p team is its capacity to adapt in an immediate way to all possible situations, to cope with all the hazards of technical, institutional, and human realities, to overcome any obstacles without getting people in the position of not abiding by the rules clearly established by the institutions and without compromising the manner in which they envision their own practices.

Trombone workshop at Lyon II University, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (26’52”-27’54”)

4.3 The Workshop « Sound Laboratory » in the Lyon II University Amphitheatre

Jean-Charles François :

The last workshop of the morning, “Sound Laboratory”, led by Giacomo Spica Capobianco, bringing everyone together in the performing space of the amphitheater, in a situation quite similar to that described on the CNSMDL day, provided an opportunity to observe several new phenomena. While the system of color-coded cards worked very well as a common element in all workshops, its use in the large group performance regrouping all the activities in the amphitheater was less obvious. One variance is dealing here with differences of cultural conceptions: in the case of the young Africans, one can imagine that contrary to the CNSMD students, they rarely had the experience of working with a conductor. Most of them were playing without taking notice of the indications given by the conductor, the pleasure of a very new activity meant that they were more focused on their own sound production. On the other hand, some of them took great pleasure in assuming the role of conductor, with the idea of being in power to sculpt the sound matter. In the case of a very young refugee who conducted on two occasions (during the two days), we could observe a real progress in his way of determining the performance. The visual practices of respecting written organizations are not necessarily present in the conceptions that one can have of musical practices. How can we resolve the meeting of a diversity of conceptions of oral (aural) communication and their eventual structuration by visual representations?

Sound laboratory at Lyon II University, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (34’55”-35’15”)

At the end of the morning, Giacomo invites the refugees to come back the next day for playing in the public presentation at 5 pm (they won’t be able to stay for the concert by the Orchestre National Urbain, as they must imperatively be back at the Refugee Accommodation Center before 8 pm). Giacomo, seeing the positive aspects of the morning, expressed in private the idea to propose to the Accommodation Center to continue to work with young residents on a regular basis, even if the stay for anyone in these centers is only for a very short time.

Guy Dallevet, visual artist, « La Sauce Singulière », Biennale Hors Normes, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (26’11”-26’50”)

4.4 The Public Presentation of the Work at Lyon II « Lumière » University

Jean-Charles François :

This public presentation of the work of the various workshops took place on September 22 at 5 pm, in the large amphitheater of the Lyon II University.

Most of the refugees from the Lyon 1 Center have returned, but they absolutely have to be back there before 8 pm. The same four CNSMDL students are actively present. An indeterminate number of other Lyon University students, visitors or observers are also there, not necessarily as participants in the performance. The members of the Orchestre National Urbain are also there: Giacomo Spica Capobianco, Lucien 16s, Sabrina Boukhenous, Selim Penaranda, Odenson Laurent, and David Marduel. Karine Hahn, Joris Cintero, Noémi Lefebvre, and Guillaume Le Dréau are present representing the FEM at the CNSMD. Some of these members of the project team also take part in the performance from time to time. Guy Dallevet is present as he led the painting workshops, as representing the Hors Norme Biennial, and as president of the organizing association La Sauce Singulière.

8 different groups present 8 performances based on the same organization of instrumental stations representing the various workshops, the conductors change each time and use the color-coded cards principle.

Several questions come to mind when observing this public presentation taking place. One wonders whether there is any point in staging such an event in front of an audience. It’s the same questions that were raised in the CNSMD courtyard, presenting imperfect things in progress, and at odds with the requirements of professional performing arts. Yet there are important reasons for publishing, for reporting on what is being done: not only the main objective of the workshops is directly linked to a practice that only make sense in a public presentation, but the act of making a given activity public determines that it is not left in the secrecy of the workshop spaces, that it is offered to the critical scrutiny of all, it’s a question of laying the cards on the table. This is what differentiates the ethical idea of public education from the possible sectarian tendencies of the private sector.

The public presentation is not the simple repetition of the workshop situation. Other issues come to the fore on this occasion:

- The perspectives of a public presentation refocus the performers’ attention on the need for personal commitment and for particular presence on stage.

- To repeat the same but in a different context with additional challenges, changes the performance conditions and enriches it considerably..

- This situation also in a subtle way encourages encounters and exchanges between the diverse groups present, because the performers pay less attention to the material contingencies and have more freedom of expression.

Two questions remain in relation to the color-coded cards:

- Is the situation of an ensemble or orchestra that follows the instruction given by a conductor encouraging personal commitment, or on the contrary gives way to the possibility to hide within the mass.

- The color-coded cards can prevent the search for other temporal and organizational solutions, particularly in trying out textures and micro-variations.

These questions are important but may not automatically apply to a kind of project that is so limited in duration and involves such radically different groups.

Here are comments from a young refugee, Bouhé Adama Traoré, who participated to the Orchestre National Urbain’s project in 2024 at the Lyon III University:

Bouhé Adama Traoré, extract from video “Du corps aux mouvements, du geste aux sons” (21’31”-22’12”)

After this public performance and before the concert by the Orchestre National Urbain, refreshments were served in the BHN exhibition hall, unfortunately without the presence of the young Africans.

Part V : The Aesthetic Framework of the Idea of Collective Creation

Karine Hahn, Lyon CNSMD, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (18’43”-20’07”)

Jean-Charles François :

The idea of collective creation is at the core of the Orchestre National Urbain project: for collective creation to become a reality in groups that are heterogeneous in terms of geographical, social, and cultural origins, it is absolutely essential to avoid one particular group dictating its own rules and aesthetic conceptions to others. For example, accomplished musicians (as is the case with CNSMDL students) should not use their own instruments, in order to put themselves in a position of equality with those who never practiced music. And to give another example, people coming from other outer-European geographical spheres should not use songs or playing techniques issued from their own tradition.

Joris Cintéro, Lyon CNSMD, extract from video “Biennale Hors Normes” (28’50”-30’28”)

Joris Cintéro :

Several observations can be formulated concerning these issues. The first one relates to the many ‘holds’[2] offered by the device (or set-up, or agencement)[dispositif][3] to the participants, particularly when they are not musicians. In the context of an intervention like that of the Orchestre National Urbain and in these circumstances, we can consider that what is initially planned, in particular the workshops, is constantly put to the test[4] of what happens (unsuitable venues, reluctant protagonists already present and, of course, people wanting to participate when they feel like it). In this respect, this brief moment shows the extent to which this device manages to overcome the ‘test’ of its audience. In fact, the nature of the instrumentarium (which has little to do with previous ‘familiarity’ and the symbolic effects it can convey), the absence of prior aesthetic codes (which presupposes knowledge and/or mastery), of prescribed ways of doing things (holding the instrument in such and such a way) and the simplicity of a colour code that is accessible to all sighted people means that participants can expand their numbers as much as possible, along the way and simply by presenting the colour code. In the circumstances of a place where the passage of people seems to be the norm (apart from children, few people seem to stand outside), the plasticity of the system is its main strength.

Another comment concerns the ‘framing’ of the dispositif by Orchestre National Urbain members. I hypothesize here that one of the conditions for the success of the members of this ensemble is that it has a major role to play in distinguishing itself from the other protagonists involved. This seems to be an important issue insofar as, if there really are tensions between the residents of the Grandes Voisines and the social workers working there (as we will learn on several occasions during the day), it is in the Orchestre National Urbain’s interest to mark its distance from the latter, and to do so in several ways. It seemed to me, at least in the speeches and in the way they acted, that there was a desire to set themselves apart through the type of ‘culture’ they were promoting (which was opposed to the French chanson promoted by the Grandes Voisines representatives), in the way they took over the premises (without much success), and in the way they addressed others (by showing a form of friendliness, which, without being overdone, was a way of doing things for all the members of the Orchestre National Urbain that I was able to observe).

Jean-Charles François :

An interesting event took place in the BHN exhibition space, at a certain informal point in the morning:

A sound sculpture was exhibited in the space made of percussion instruments and various metal objects, driven by an automatic mechanical system. The sculpture was capable of developing highly rhythmic music for 45 minutes without any repeating sequences. A group of 5 or 6 refugees stood in front of this sound sculpture, and as the music of the machine was playing, they started to sing and dance music that they knew, for about ten minutes.

This situation leads to me to make three comments relating to the idea of avoiding one’s own cultural habits in the perspectives of being able to work with anyone else in constructing a collective artistic act:

- This is a spontaneous situation that must not be prevented.