Interview de Djely Madi Kouyaté

par Jean-Charles François et Nicolas Sidoroff

en présence d’Olivier François

Le 29 octobre 2022 au Petit Bistrot, Paris

Le 20 décembre 2023, à la Bidule, Paris.

Édition 2023-2025

Jean-Charles François et Nicolas Sidoroff.

Sommaire :

1. Enfance et adolescence au village

2. Les Kouyatés, une famille de griots.

3. Partir à l’aventure

4. L’électricité, l’amplification, les technologies

5. La Côte d’Ivoire

6. Le jeu du balafon

7. La vie en France et en Europe

8. Conclusion

1. Enfance et adolescence au village

Jean-Charles François :

Notre idée c’est un peu de retracer votre parcours depuis l’enfance jusqu’à aujourd’hui, mais aussi de décrire en détail les pratiques que vous avez pu développer au cours de votre vie.

Djely Madi Kouyaté :

OK, on commence ?

Nicolas Sidoroff :

Si vous voulez, sinon on va chercher un café…

Photo Nicolas Sidoroff.

[Interruption du cafetier pour prendre les commandes]

Ah mais ça coupe quand il y a quelqu’un qui demande… [rires].

Alors je peux continuer ?

Olivier François :

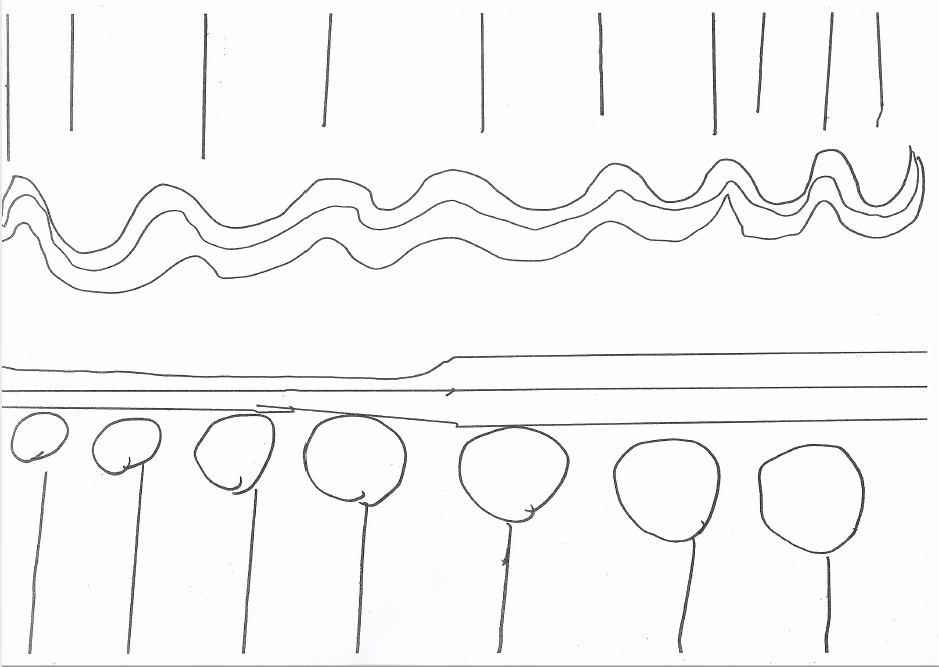

On ne porte pas trop attention aux enfants, on les surveille mais de loin. Ils écoutent une répétition ou une fête et se mettent ensemble, prennent des boîtes de conserve et tapent dessus, quand ils veulent et ils apprennent comme ça.

Et quand j’arrive enfin à faire cela, je commence à porter le balafon moi-même. Alors c’est comme ça qu’on se perfectionne jusqu’à un certain âge, quinze ans. Comme ça, je joue, je joue, je joue et les gens commencent à parler de moi : « Ah ! Il y a le petit là, à Kamponi (mon village), il joue très bien, s’il y a un mariage, on va aller le chercher ». Parce que, à l’époque, dans le village où je suis né, il n’y a pas d’école, il n’y a pas de téléphone, il n’y a pas d’activités comme dans les grandes villes. Maintenant, cela fait deux ou trois ans, il y a une école.

Exemple du Boté (tambour et cloche)

[Vidéo des enfants qui jouent sur des balafons]

Là, ce n’est pas moi qui ai montré cela. Le plus grand a écouté quand je joue et il a aussi joué. Ici il commence à jouer pour son petit frère.

[Fin de la vidéo]

C’est comme ça, les enfants, quand ils s’intéressent, eh bien, quand ils ont grandi, on voit quelque chose de bien. Tu vois, ça va être joué une fois ou deux, il écoute, il comprend, il joue. Et ceux qui l’écoutent, ils viennent, ils jouent. Voilà, c’est comme ça.

2. Les Kouyatés, une famille de griots.

3. Partir à l’aventure

4. L’électricité, l’amplification, les technologies

5. La Côte d’Ivoire

Au début, je jouais le balafon dans le groupe, mais le balafon n’était pas bien accordé. Il y avait deux autres balafonistes dans le groupe, c’était moi le troisième. Moi j’écoute et je dis : « Ah ! le balafon, l’accord n’est pas bon, moi à l’oreille je le sens ». Alors ils ont dit « Non, non, non c’est comme ça ». Alors j’ai dit « Bon ! » Mais une fois, le directeur m’a dit qu’il fallait accorder le balafon. J’ai dit : « Oui ». Lui, il a dit : « Bon ! tiens ! il y a deux balafons ici, tu vas l’accorder et tu me l’amènes dans une semaine ». J’ai dit « OK ». Je prends les deux balafons, je les amène dans ma maison, je commence à accorder le balafon. À l’époque il y a un diapason, on entend le son, comment ça sonne. Alors j’ai accordé le balafon en do majeur. Le balafon a sept notes. Bon, je trouve que ça devait être comme ça. J’ai accordé l’autre balafon, pareil, bien accordé. Je l’ai amené à la répétition. On a commencé à jouer, il était loin le directeur Souleymane Koly, il est venu, il a regardé, il a regardé. Quand la répétition a été finie il m’a appelé, il a dit : « C’est toi qui as accordé le balafon ? », j’ai dit « oui ». Il a dit : « C’est vrai ? », j’ai dit « oui ». Il a dit « OK ». Après, il m’a appelé, il a dit : « Bon ! tu es retourné dans le groupe, tu ne dois pas bouger ». Des fois, je venais à la répétition, des fois je ne venais pas, parce mon intention n’était pas de rester dans le groupe, je ne voulais pas rester dans le ballet. Mais il m’a forcé à rester dans le groupe. Il a dit : « Voilà, écoutes, tu dois venir aux répétitions tout le temps ». J’ai dit « OK ». Alors, il a gardé les deux balafonistes dans le groupe. Il m’a demandé d’être le leader du groupe. Et voilà comme on est resté dans le groupe. On a fait des tournées, des tournées, des tournées. À la fin, je me suis dit qu’il fallait que j’évolue pour toujours connaître d’autres choses. J’ai quitté le groupe et je suis venu m’installer à Paris vers 1988-89.

6. Le jeu du balafon

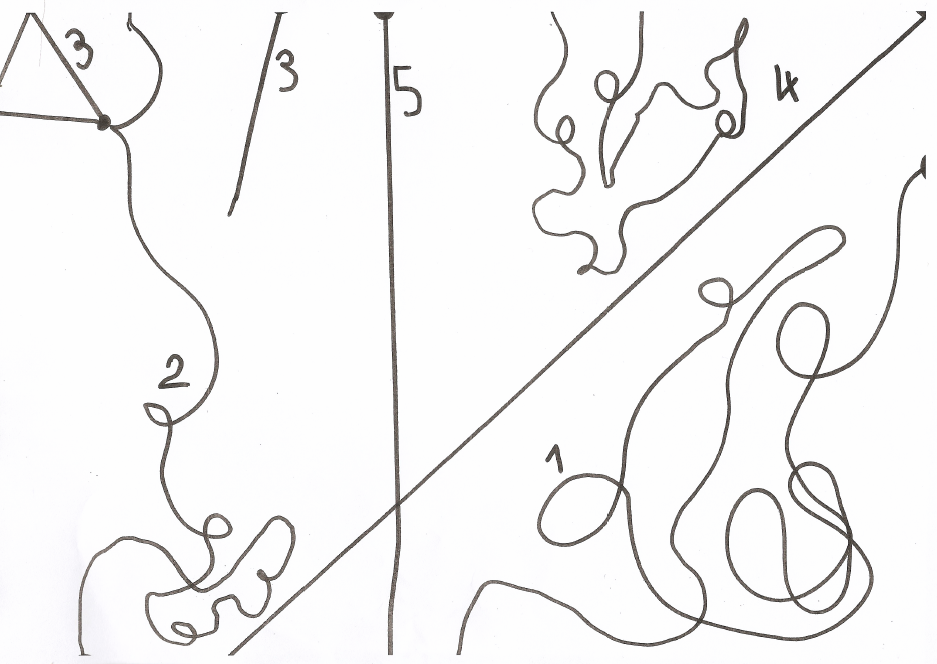

Après il peut y avoir des changements, et quand tu commences à changer, ce n’est pas seulement que vous allez vous regarder, mais c’est de comprendre ce qui va changer. Et c’est facile de se rattraper sans se tromper, sans se tromper de notes, et voilà. Tu commences à comprendre, quand tu commences, ou bien tu fais un clin d’œil comme ça, tu fais, et l’autre sait que tu vas changer. Et même sur scène, on fait comme ça souvent, avec les yeux on se regarde. Ce n’est pas la peine de parler, mais avec les yeux comme ça on se parle.

Voix : ti titi ti titi

Mains : x x x x

C’est ça, c’est le « ti titi ti titi » qui donne le tempo.

Des fois, je joue des choses que je n’ai jamais entendues, mais tout en écoutant je dois tout de même jouer. Même au studio, quand parfois on m’appelle pour venir jouer, je demande seulement la gamme des morceaux, c’est ça qui m’intéresse. Quand j’arrive, j’écoute et je joue direct sans perdre de temps. Le balafon est un peu limité par le nombre de notes par rapport à la guitare ou au saxo. Le balafon a sept notes seulement, et non pas douze. Donc, je cherche à savoir quelles notes vont être jouées, et comme ça je sais si c’est mineur ou majeur, je sais comment je peux m’adapter pour jouer. Et s‘il y a des demi-tons chromatiques, quand j’arrive au studio je dis : « Ben ! vous faites tourner la musique » et je joue après avoir écouté pour me donner le temps de m’adapter à ce que jouent les autres.

7. La vie en France et en Europe

Je me rappelle bien que j’ai dû jouer aussi avec pas mal de groupes différents qui sont connus en Afrique, comme celui de Youssou Ndour. J’ai joué avec lui et Kandia Kouyaté, Oumou Kouyaté et Diaba Kouyaté. Il y a aussi Ami Koïta. J’ai joué avec Manfila Kanté pendant longtemps, on a beaucoup joué ensemble en Hollande, en Belgique.

8. Conclusion

2. Wikipedia.fr : griots. « Organisation sociale des griots mandingues. Chaque famille de djéli accompagne une famille de rois-guerriers nommés diatigui. Il n’est pas de djéli sans diatigui, il n’est pas de diatigui sans djéli, les deux sont indissociables et l’un ne vaut rien sans l’autre. » wikipedia

3. african-avenue.com : « Le Bazin riche est un type de tissu très populaire en Afrique : notamment pour la confection des tenues africaines originales, des vêtements traditionnels en Afrique de l’Ouest, en particulier au Mali, au Burkina Faso et au Niger. Il s’agit d’un tissu luxueux et unique qui se décline en différentes couleurs et motifs (…). » african-avenue.com

4. Soundiata Keïta aussi appelé, selon la tradition orale, Mari Diata Konaté (et couronné sous le nom de Mari IerDiata ), né le 20 août 1190 à Dakadjalan au royaume du Manding et mort en 1255, dans l’empire du Mali, est un souverain mandingue de l’Afrique de l’Ouest, présenté par la tradition comme le fondateur de l’empire du Mali au xiiie siècle. L’histoire de Soundiata est essentiellement connue à travers une épopée aux tonalités légendaires racontée de génération en génération jusqu’à nos jours par les griots. wikipedia

5. Yankadi : « Le yankadi est l’une des danses traditionnelles soussou bien connu et souvent utilisé par les artistes pour mieux toucher la sensibilité des amoureux. Comme tous les autres rythmes traditionnels de la Guinée, la danse yankadi obéit à des techniques de chants et de danses spécifiques. » wikipedia

6. Sékou Camara Tanaka, ou Sékou Camara Cobra est un griot de la tradition Malinké. Il chante et joue de la guitare. Il est aussi acrobate, chorégraphe et compositeur. iro.umontreal.ca.

7. Le groupe Kotéba est une compagnie de théâtre de Côte d’Ivoire, basée à Abidjan, fondée en 1974 par Souleymane Koly. Souleymane Koly (1944-2014) est un producteur, réalisateur, metteur en scène, dramaturge, chorégraphe, musicien et pédagogue guinéen. Voir wikipedia et Souleymane Koly, wikepedia.

8. Fodéba Keïta (1921-1969). Voir wikipedia.

9.« Famoudou Konaté est considéré par ses pairs comme l’un des plus grands batteurs de l’ethnie malinké ». wikipedia.

10. Mory Kanté a popularisé la Kora avec le tube planétaire Yéké Yéké, en 1986.

11. George Momboye, « chorégraphe d’origine ivoirienne, initié très jeune à la danse africaine puis plus tard à la danse jazz, classique et contemporaine. » Centre Momboye.

12. Philippe Monange : formé au piano classique puis jazz parallèlement à des études de philosophie, aujourd’hui passionné de musiques africaines il se produit actuellement avec le Bal de l’Afrique enchantée, Debademba, Vincent Jourde quartet, créateur de l’Akrofo system. linkedin.com.

Steven Schick – English

Encounter between Steven Schick and

Jean-Charles François

January 2018

Percussionist, conductor, and author Steven Schick, for more than forty years, has championed contemporary percussion by commissioning or premiering more than one hundred-fifty new works. He is artistic director of the La Jolla Symphony and Chorus and the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players. Steven Schick is Distinguished Professor of Music and holds the Reed Family Presidential Chair at the University of California San Diego. (see www.stevenschick.com)

The interview is about John Luther Adams’ Inuksuit (2007), which was performed under the direction of Steven Schick in January 2018, on the border between Mexico and the United States, with the musicians equally divided between the two sides of the border “wall”.

To begin with, it should be noted that John Luther Adams[1] is not known at all in France. Could you give us an idea of who he is?

I know that he is not known, because when I gave a master class on “Manifeste” for the 70th anniversary of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, I proposed this Inuksuit piece, and they didn’t know it. So it is not a surprise that you say that. John Luther Adams is a composer who at an early age moved to Alaska instead of pursuing more traditional routs to success as a composer in the United States. And he lived there for – I do not know exactly – for about 25 years. And he still has his own studio in the Alaskan forest, but he does not live there anymore. He now lives in New York and often also in the desert in Chile. Even though he no longer lives in Alaska, I think this notion of space in his music is still completely part of his language. And he was early interested in establishing relationships between music and nature in a personal way, with some dramatic pieces: in his play Earth and the Great Weather, there are things that could actually be staged, and quite a number of shorter solo pieces, etc. About 7 or 8 years ago, he started writing much bigger forms, orchestra pieces and large ensembles and quite a lot now written for orchestra and very large choirs. This seems to be kind of a big change, first of all not only in his usual music, but also in his recognition, that brought him to the attention of a much bigger public. The critical moment that marked this change was probably the piece Become Ocean. I’ve worked with him for a very long time: he wrote a piece for percussion, Mathematics of the Resonating Body in 2002, and then I co-commissioned a piece for a chamber ensemble, Become River, and also a piece for the La Jolla Symphony, Sila, to be performed outdoors. (see www.johnlutheradams.net)

Looking at the video[2], it was difficult for me to imagine what this Inuksuit piece was all about.

No, I am sure, I think that’s a fairly short visit.

Could you describe how it works?

Inuksuit was written in 2007 and I think the premiere took place in 2009 at the Banff Center[3] (Canada). It is written for 9 to 99 percussionists divided into three groups, so it is multiples of 3 in relation to the forces that can be solicited. In addition, there is a small group of piccolo players who can come and join at the end. The 3 groups of percussionists start from a central spot, then the first group leaves this place and starts to move outward in space, making some wind sounds – with megaphones, and different things like that, so breathing sounds. The second group has tubes that it spins in the air to make wind sounds and other kinds of things. The third group does something else. Gradually the three groups move to their spaces, and then the piece starts with a set of interactions between the groups. So group A would start with something that will trigger a response from group B and group C. Everybody plays their individual parts and so there is that kind of shifting overlay of these textures, which starts soft, and reaches very loud levels with drums, sirens and gongs, and things like that. And then, at the end of the piece, which is about one hour long, gradually all the percussionists come back to the center. The piece ends with again with wind sounds and bird songs. I think the New Yorker’s video shows a sequence that happens towards the beginning of the piece, which makes it seem like it’s just a bunch of scattered elements. But when you listen to the piece over the large scale, you’re going to hear these big waves of sounds and events that propagate out in space.

All the performers have independent parts?

They have independent parts and stopwatches.

So it is not conducted?

It is not conducted, and in fact you don’t really need a stopwatch, because you just need to know the sound signals that cue trigger events. One person from group A – that was often me – gives the starting cue to go ahead in it.

Is the composer’s intention to develop a situation in which amateur musicians coexist with professionals?

Not really. I think that the different instrumental parts require professional musicians, even in group A, which is the easiest with conk shells and triangles (groups B and C are actually difficult parts). I think that sometimes the piece is played by student percussionists and local amateurs. It’s something that will work for example in some Michael Pisaro’s pieces. But that doesn’t really work for John’s piece, which is really much harder to play. Even though I don’t think it’s very difficult for professional musicians, it’s certainly difficult for amateurs. That’s what the piece is all about, and so I had the idea of doing it on the border with half the musicians playing on the Mexican side, and the other half on the US side – normally the piece is played in one place – but in the meeting at the center where the piece starts and ends, then the border runs at the middle of the musicians. There were 35 percussionists on one side and about the same number on the other side, about 70 in all, and then you kind of radiated around in the space. On the Mexican side of the border, the park extends along the border but is reduced in width, so they could not move very far from the border, but they moved in length. On our side (United States) we could move farther from the border. So we were in the presence of a sort of strange shape, but despite everything we could hear each other, we could hear the cues very clearly crossing the border back and forth. But this concert almost didn’t take place…

Because of the border?

Because of a lot of things, but it has to be said that Border Patrol – I think it’s really important to say this – was very supportive. Not everybody, but there was a group of Border Patrol agents without whom the piece could never have been presented. Did you go to the Friendship Park, down the border (where the concert took place)?

I never been there, but I know about it.

When you go to visit it, it doesn’t look very friendly, especially on the US side it does not look friendly at all. But when I started thinking about doing this concert, someone from Border Patrol said to me, “If it rains, you wouldn’t be able to do the concert”. And I said, “OK, it makes sense.” But what he meant by that was that if it ever rained before the concert, the roads would be flooded and impassable. And so there was rain in the days before the concert and they said, “you can’t go, the roads are all closed”. I thought, “My God!” So we tried to consider all the solutions: we thought we could put the instruments on a pick-up truck and drive it along the beach. But the Border Patrol insisted that if we tried to do that, the pick-up truck would be stuck in the sand and it could catch fire, etc. I then thought that if we can get enough people, we would have everybody carry an instrument, we would be able to play the piece with a minimum of instruments. Now it was a two-miles walk, it was never going to work. But then at the last minute – and actually after we decided to cancel the concert – a Border Patrol agent with whom we had developed a good relationship said, “Look, this seems a nice idea: there’s an unofficial paved road that no one is allowed to use except Border Patrol; but if you come at 9 a.m., we will open it for 10 minutes, and you can drive your instruments in.” That’s what we did, so the audience had to walk the two miles on the beach. I think there were between 300 and 400 people on the US side, and about the same number on the Mexican side. And the great thing was at the end of this piece – the music fades out, so that you are really never sure when the performance is over, there’s a silence, and then there’s another little bird call, and then there’s more silence, and you wonder if that’s the last sound in the piece. So there’s a lot of stillness at the end of the piece – and then, when the applause started at a certain point on the U.S. side and not yet on the Mexican side, then they responded and we stopped, and it went back and forth for about five minutes, and that kind of ovation was so amazing. So this was that piece. It was good!

What was the origin of this project? Was it a collaboration with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra?

Yes, I mean they asked me to curate a percussion festival, and I told them that I didn’t want to do it, because a percussion festival didn’t seem really appealing to me. I suggested instead a festival about places, rhythm and time, and they thought it was a good idea. In addition to the concerts in the concert halls there were concerts all over the area. And so, yes, it was part of the festival and it was my idea. But the orchestra didn’t have very much to do with that particular concert. They certainly were part of the planning of it, but very few symphony players played in it. Then, there were concerts here, there were concerts in Tijuana, there were concerts all over the place. And we presented a new version of Stravinsky’s L’histoire du soldat using a text by a Mexican poet, Luis Urrea, instead of Ramuz text: a text called “The Tijuana Book of the Dead”, which is very beautiful.

And was John Luther Adams present?

He wasn’t here for that, no.

You had some contact with him?

Yes, quite often. Even while we were doing it. We sent him pictures.

I guess it wasn’t the first event or collaboration you organized between San Diego and Tijuana, or between California and Mexico?

Of course. We have done several projects: I had a long partnership with the Lux Boreal Dance Company in Tijuana, and with Mexican musicians, and the band Red Fish Blue Fish played there regularly. And in addition, as you know, there are the concerts that I personally give in Mexico. But in terms of organization, these are the most important projects. And I’m going to organize the festival again in 2021 and I think I’ll continue to organize collaborations with both sides of the border.

And you have a lot of students from Mexico?

Yes, that’s true, but saying “a lot” is probably not true. The most important one was Ivan Manzanilla – did you know him?

Yes, I met him in Switzerland.

Now I see him quite frequently. He came from Mexico with six of his students to perform John Luther Adams’ piece. He wrote me a text the night before, he said, “My students have never been on an airplane!”

So, do you think the wall will fall?

What was interesting about the whole thing is that I was very sensitive to the impression that it was a protest demonstration. Because if we had taken that approach, we would never have gotten the permission to do it. There has been a lot of things that were organized around this issue: there was a German chamber orchestra that wanted to get permission, and it was clearly a protest movement against the Trump administration, and obviously nothing like that would be allowed. I wanted to be very respectful to the customs services because they treated us very well. Of course, there is a political element in this project and you cannot help but think of the fact that human connections and sounds pass easily through space and that there are walls that can never prevent that. You don’t have to unpack all the poetry that goes with this idea of a wall. But you should know that Al Jazeera was there to report on this event, too, and they really wanted it to be a protest. And so there was a little friction around that, and even the San Diego papers wanted to know if that was part of the resistance to Trump. We were probably like-minded about the Trump administration, but at the same time I had another idea about what to do about that, and I think that resistance is not how I think of it. In any event, it was evident that it had political value, and certainly there was no one who was there who was not thinking about that. But it had other components to it as well.

And – may be it would be the last question – are there also walls to break down in the world of music and the arts?

Well, one of the biggest wall is the one that encloses a concert hall. We rarely think consciously about the existence of walls. For example, several people have asked approached me to do the piece based as a sort of healing mechanism, to go to a given place, which has a wound, and to play that piece as a sort of way to addressing that. The fires north of Los Angeles in Ojai were the first proposal in this direction: it was to play John Luther Adams’ piece in the fire zone. And I talked to John about it, and I was a bit resistant to do that, because I wanted to avoid the piece becoming this sort of shapeless happening in a situation that adopts whatever political value is put into. I didn’t immediately leap on that idea. Like, for example, taking this piece and performing it in other parts of the wall on the border with Mexico or in Jerusalem, or in other parts of the world. The most beautiful part about that piece, I think, which makes it suitable to this kind of experience, is that at the very end, after listening to an hour of this music, where in order to make sense, everyone has to focus intensely on sound production, the piece fades out and there are still five hundred people, or whatever, listening really, really intensely, and all you hear are the sounds of nature. There is something really extraordinary about that, you can actually hear yourself, you hear your neighbors, and you hear the wind. It is therefore a tool that makes it possible to hear what is happening in a place. And as long as we keep this aspect as one of the main values of the piece, it could be exported to other places.

But my question was also about all kinds of walls.

You mean, not simply the physical walls, but also other kinds of things?

Yes, the example that can be given in our context concerns popular music versus the avant-garde of Western classical music. My question is outside of John Luther Adams’ piece and its performance.

Thank you for clarifying. This is exactly what we seek to do in the proposal made at the Banff Center: try to make the cloture disappear, which seems more than a handcuff than a tool these days. I mean people use these words, which don’t have any meaning any more. So, if someone asks me: are you a classical musician? I wouldn’t know what to say. It’s really a very important kind of thing, but I think the mechanism to address these questions has got to be really very sophisticated, because the problem is complex. I think it’s about going beyond a simple “feel good” moment in which everybody would recognize that: “All right, we have a problem, there’s a wall here.” But if you actually want to do something about this problem, I don’t have to tell you how difficult and complex the task will be, when you realize how many people’s minds you have to change, and how much prejudices and biases you have to encounter. That’s the work we did in Banff – I don’t think it is happening here in San Diego in the music department so much, although there’s a little bit of that. It is critical to be able to do that, so the answer of course is “yes” and you have to find a suitable mechanisms for each case.

Thank you.

Thank you.

Transcription of the recorded encounter (in English) and French translation: Jean-Charles François.

___________________________________________________________________________

1. John Luther Adams is not to be confused with the more famous composer John Adams.

2. The New Yorker published an article by Alex Ross, on the performance of Inuksuit presented between Tijuana et San Diego, with a short video. See https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/making-the-wall-disappear-a-stunning-live-performance-at-the-us-mexico-border

3. See the Banff Centre : https://www.banffcentre.ca

Christopher Williams

Encounter between Christopher Williams and

Jean-Charles François

Berlin, July 2018

Summary :

1. The Concert Series KONTRAKLANG

2. Public Participation

3. The Question of Immigration

4. Mediation

5. Artistic Research – A Tension between Theory and Practice

1. The Concert Series KONTRAKLANG

To begin with, I wanted to propose we talk about my activity as a curator, because I think it speaks to the topic of this issue. In Berlin, I co-curate a monthly concert series called KONTRAKLANG (www.kontraklang.de). In a place like Berlin where you have a higher concentration of people doing contemporary music than anywhere else in the world, and at a very high level, it happens that people specialize, and they don’t necessarily see themselves as part of a bigger ecosystem. For example, some people in the sound art scene might go to galleries or have something to do with the radio, but they don’t necessarily spend much time going to concerts or hanging out with composers and musicians. Then you have, as you know, composer-composers who only go to concerts of their own music or to festivals to fish for commissions, or occasionally to hear what their friends are doing. And then you have improvisers who go to certain clubs and would never go to conventional new music festivals. Not everyone is like that of course, but it is a tendency: humans like to separate themselves into tribes.

There is nothing wrong with that?

Well, I mean, there is something wrong with it, if it becomes the super-structure.

Yes. And within the improvisation world you have also sub-categories?

Yes. Even though the pie is small, people feel the need to cut it up into pieces. I don’t mean to dwell on that as a permanent condition of humanity, but it is something that’s there – and which we wanted to address when we started KONTRAKLANG four years ago. We wanted to derail this tendency and to encourage more intersections between different mini-scenes. In particular, we gravitate toward forms of exchange, or work that has multiple identities. Sometimes, often actually, we have two-part concerts, one set – break – one set, in which these two sets are very different aesthetically, generationally, etc. But they might be tied up with similar kinds of questions or methods. For example, a couple of years ago we did a concert about collectives. We invited two collectives: on the one hand, Stock11 (http://stock11.de), a group of composers-performers, mainly German, who are very much anchored in the “Neue Musik” scene; they presented some pieces of their own and played each other’s works. And on the other hand, we presented a more experimental collective, Umlaut (http://www.umlautrecords.com/), whose members do not perform together regularly, but they are friends; they have a record label, a festival, and a loose network of people who like each other, but don’t have necessarily have a common musical history. They had never actually played a concert together as “Umlaut”; and now we asked them to perform a concert together. I think there were five or six of them and they made a piece together for the first time ever. So, the same theme applied to both sets, but it manifested under very different conditions, with very different aesthetics, very different philosophies about how to work together. This is the sort of thing we dig. Even when there is no nice theme to package the diversity, there is usually a thread that connects the content and highlights the differences in a (hopefully) provocative way. This is something that has been very fruitful for us, because it creates occasions for collaborations that wouldn’t normally be there, you know with festivals or institutions, and also I think, it has helped develop a wider audience than we would have if we were doing only new music, or improvised music, or something more obvious like that. We also invite sound artists: we have had a few performance-installations as well as projects involving sound artists who write for instruments. Concerts are not necessarily appropriate formats for people doing sound art, because they generally work in other sorts of spaces or formats; performance is not necessarily part of sound art. In fact, in Germany, especially, it is one of the walls, let’s say, that historically has been constructed between sound art and music. It is not that way in other places necessarily.

Is it because sound artists are more connected to the visual arts?

Exactly. Their superstructure is the art world, generally speaking, as opposed to the music world.

Also, they are often into electronics or computer-generated sounds?

Sometimes. But, as an American, my understanding of sound art is more ecumenical. I don’t really know where to put a lot of people who call themselves sound artists but also do music or vice versa. Nor do I really care, but I mention it to provide a background for our taste for grey areas in KONTRAKLANG.

2. Public Participation

It seems to me that for many artists who are interested in sound matter, there is a need to avoid the ultra-specialized universe of musicians, which might be a guarantee of excellence but a source of great limitations. But there is also the question of the audience. Very often it is composed of the artists, the musicians themselves and their entourage. I have the impression that today there is a great demand for active participation on the part of the public, not just to be in situations of having to listen to or contemplate something. Is this the case?

Are listening and contemplating not active? Even in the most formal live concert situations, the audience is physically engaged with the music; I do not really relate to the concept of participation as a separate layer of activity. Everything I do as a musician is quite collaborative. I almost never do something by myself, whether making written pieces for other people or making pieces for myself, or improvising, even when it’s ostensibly “alone”. There is always some very clear aspect of sharing. And I extend that notion of course to listening as well, even if listeners are not voting on what piece I should play next, or processing my sounds through their smartphones or whatever. Imagination is inherently interactive, and that is good enough for me. I don’t really spend too much time on the more overtly social participation that is hyped in pop music or in advertising, or even curating in museum contexts nowadays. I am quite skeptical actually. Did you ever come across an architect and thinker called Markus Miessen?

No.

He wrote a book called The Nightmare of Participation,[1] in which he takes apart this whole idea, and critiques the kind of cynical mindset behind “Let the people decide.”

Yet active public participation seems to me to be what constitutes the very nature of architecture, in the active adaptation of spaces and pathways by users, or even their actual modification. But, of course, the process is as follows: architects build something out of a phantasm of who the users are, and then the users afterwards transform the planned places and pathways.

Well, architecture definitely offers an interesting context for thinking about participation, because it can be present in so many different ways.

Usually, the public has no choice but participating.

They have to live there. Are you familiar with Lawrence Halprin’s work?

Yes, very much. “RSVP Cycles”.[2]

As you know, I wrote a chapter about it in my dissertation and I have been dipping into his work over the last couple of years. I also took a dance class with Anna Halprin, his wife, who was equally responsible for that whole story. She is ninety-eight now and still teaches twice a week, on the same deck where she has been teaching since the 1950s, it’s amazing. Anna still talks about RSVP Cycles a lot. Her view of RSVP is simpler and more open than her husband’s: he had a more systematic idea about what it should do and how to use it. It is fascinating to compare the utopian sense of participation in his writings with how he actually implemented it in his own projects. In her book City Choreographer Lawrence Halprin in Urban Renewal America,[3] Alison Bick Hirsh views Halprin’s work with sympathetic eyes. But she also offers a critical view of the tension between his modernist sensibilities and his need for control and, on the other hand, his genuine desire to maximize the potential of public participation at different levels.

The project I use in my dissertation to unpack the principles of RSVP is the Sea Ranch, an ecological community in Northern California. If you saw it, you would recognize it immediately because the style of architecture has been copied so widely: unfinished wood siding with very steep roofs and big windows – very iconic. He developed this kind of architecture for that particular place: the slanted roofs divert the wind coming off the ocean and create a kind of a sanctuary on the side of the house not facing the coast. The wood siding derives from a feature of historical regional architecture, the barns that were built there by Russian fur traders before the land was developed. He and his many collaborators also drew up ecological principles for the community: there were rules about the kind of vegetation to be used on the private lots, that no house should block the view of the sea for any other house, that the community should be built in clusters rather than spread out suburb-style – these sorts of things. And pretty soon this community became so sought after, because of the beauty and solitude, that basically the real estate developers ran all over his ecological principles.

Ultimately they let him go and expanded the community in a way that totally contradicted his original vision. This project was based on the RSVP Cycle, that is, on a model of the creative process that prioritized a transparent representation of interactions between the Resources, the Score, the Value-actions, and the Performance. But the power of purse hovering over the whole process, which kind of rendered everything else impotent at a certain point, is not represented in his model. This asymmetrical power dynamic was apparently a problem in more than one of his projects. It was not always based on money, but sometimes on his own vision, which wasn’t represented and critiqued in the creative process.

That’s the nature of any project, it lasts and suddenly it becomes something else, or it disappears.

Some of his urbanist projects were extreme in this way: a year’s worth of work with the community, meeting with people, setting up local task forces with community representatives, organizing events, and taking surveys… and then ultimately he would shape the project to reach the conclusions that he wanted to reach in the first place! I can understand why it would be the case, in a way, because if you let the people decide complex issues, it can be hard to reach conclusions. He didn’t do that, I think, because of his training and his strong aesthetic ideals, which were very much rooted in the Bauhaus. He studied at the Harvard Graduate School of Design with Gropius. He could not, at a certain level, escape his modernist impulses. In my experience, authorial power structures rarely disappear in these kinds of participatory projects, and it’s wise to accept that and use it to the collective advantage.

In that same chapter in my dissertation, I talk about a set of pieces by Richard Barrett. He is an interesting guy, because he’s an illustrious composer-composer, who’s often worked with very complex notation, but he has also been a free improviser throughout his career, mainly on electronics; he has an important duo with Paul Obermayer called furt. Fifteen years ago or so Richard started working with notation and improvisation together in his projects at the same time, which was kind of unheard of in his output – it was either one or the other up until that point. He wrote a series of pieces called fOKT, for an octet of improvisers and composers-performers. What I find interesting about this series is that his role in the project is very much that of a leader, a composer, but by appealing to the performers’ own sound worlds, and offering his composition as an extension of his performance practice, he created a situation in which he could melt into the project as one musician among many. It was not about maintaining a power structure as in some of Lawrence Halprin’s work. I think it is a superb model for how composers interested in improvisation can work. It provides an alternative to more facile solutions, such as when a composer who is not an improviser him/herself gives improvisers a timeline and says: “do this for a while, then do that”. There are deeper ways to engage improvisation as a composer if you don’t adopt this perspective of looking at performance from a helicopter.

In the 1960s, I experienced many situations like the one you describe: a composer who included moments of improvisation in his scores. Many experimental versions were already available in the form of graphic scores, directed improvisation (what today is called “sound painting”), not forgetting the processes of aleatoric forms and indeterminacy. At the time, this produced a great deal of frustration among the performers, which led to the need for instrumentalists and vocalists to create situations of “free” improvisation that dispensed with the authority of a single person bearing creative responsibility. Certainly, today the situation of the relationships between composition and improvisation has changed a lot. Moreover, the conditions of collective creation of sound material at the time of the performance on stage is far from being clearly defined in terms of content and social relations. For my part, over the last 15 years, I have developed the notion of improvisation protocols which seem to me to be necessary in situations where musicians from different traditions have to meet to co-construct sound material, in situations where musicians and other artists (dancers, actors, visual artists, etc.) meet to find common territories, or in situations where it is a question of people approaching improvisation for the first time. However, I remain attached to two ideas: a) improvisation holds its legitimacy in the collective creation of a type of direct and horizontal democracy; b) the supports of the « visual » world must not be eliminated, but improvisation should encourage other supports that are clearly on the side of orality and listening.

3. The Question of Immigration

To change the subject and come back to Berlin: you seem to describe a world that is still deeply attached to the notions of avant-garde and innovation in perspectives that seem to me to be still linked to the modernist period – of course I am completely part of that world. But what about the problem of immigration, for example? Even if at the moment this problem is particularly burning, I think it is not new. Do people who don’t correspond to the ideal of Western art come to the concerts you organize?

Actually, in our concert series we have connections to organizations that help refugees, and we have invited them to our events. Maybe you know that many of the refugees – besides the fact that they are in a new place and they have to start from scratch here without much, if any, family or friends – they don’t have the right to work. Some of them go to study German, or they look for internships and the like, but many of them just are hanging around waiting to return to their country, and of course this is a recipe for disaster. So, there are organizations that offer ways for them to get involved with society here. We have invited them to KONTRAKLANG, and it is a standing invitation, free of charge. The venue offers them free drinks. Occasionally we have had a crowd of up to twenty, twenty-five people from these organizations, and some of those concerts were among the best of the season, because they brought a completely different atmosphere to the audience. Imagine that these are mostly kids – say between eighteen or even younger up through their mid-twenties – many of whom, I suspect, have never been to any formal concert, much less of contemporary music. The whole ritual of going to a concert hall, paying attention, turning off their phones, seems not to be a part of their world. Sometimes, they talk to each other during the concerts, they get up and go to the bar or go to the bathroom while the pieces are being played. It is distracting at first, but they have no taboos about reacting to the music. I can remember the applause for certain pieces was just mind-blowing – they got up and started hooting and hollering like nobody from our usual audience would ever do. And they laugh and make comments to each other when something strange happens. Obviously this is refreshing, if sightly shocking, for a seasoned contemporary music audience. Unfortunately, these folks don’t come so often anymore; maybe we need to get in touch again and recruit some more, because it was a very positive experience. However, some of them did come back. Some of them kept coming and asking questions about what we do, and that is very encouraging. But, of course, this is an exception to the rule.

Do they come with their own practices?

Well, I don’t know how many of them are dedicated or professional musicians, but I have the impression that some sing or play an instrument. Honestly, it’s something of a blind spot.

More generally, Berlin is a place that is particularly known for its multiculturalism. It’s not just the question of the recent refugees.

It’s true that there are, here in Berlin, hundreds of nationalities and languages, and different communities. Are you curious why our concerts are so white?

4. Mediation

It is about the relationship between the group of “modernists” – which is largely white – and the rest of society. It has to do with the impression I have of a gradual disappearance of contemporary music of my generation, which in the past had a large audience that has now become increasingly sparse and had a media exposure that has now practically disappeared, all this in favor of a mosaic of diversified practices (as you mentioned above), each with a group of passionate aficionados but few in number.

In Berlin you get better audiences than practically anywhere else, in my experience. Even though you may have only fifteen to twenty people in the audience at some concerts, more often you have fifty, which is cozy at a venue like Ausland[4], one of the underground institutions in improvised music. They have been going for fifteen years or so, and they have a regular series there called “Biegungen”, which some friends of mine run. The place is only so big, but if you get a certain number of people there, it feels like a party; it’s quite a lively scene. But then again you have more official festivals with an audience of hundreds. KONTAKLANG is somewhere in between, usually we have around a hundred people per concert. So, I don’t have the impression at all that this type of music and its audience are dwindling per se. What you are talking about, I think, is rather the disconnect between musical culture and musical practice.

Not quite. To come back to what we said before, it’s more the idea of a plethora of “small groups”, with their own networks that spread around the world but remain small in size. It’s often difficult to be able to distinguish one network from another. It is no longer a question of distinguishing between high art and popular culture, but rather of a series of underground networks whose practices and affiliations are in opposition to the unifying machine of the cultural industry. These networks are at the same time so similar, they all tend to do the same thing at the same time, and yet they are closed in the sense that they tend at the same time to avoid doing anything with one another. Each network has its own festivals, stages, concert halls, and if you’re part of another group, there’s no chance of being invited. The thought of the multitude of the various undergrounds opens up fields of unlimited freedom, and yet it tends completely to multiply the walls.

The walls! Yes, that is what I mean by musical culture: how people organize themselves, the discourses that they are involved in, and places that they play, magazines they read, all of this stuff. To me, it is obviously extremely important, and it has a major impact on practice, but I don’t think that the practice is bound by it. There is a lot of common ground between, for instance, certain musicians working with drones or tabletop guitars, and electro-acoustic musicians, and experimental DJs; similar problems appear in different practical contexts. But when it comes to what is called “Vermittlung” in German, the presentation, promotion, dissemination of the music, then swshhhh… they often fly by each other completely. What interests me more, as a musician who understands the work on the ground, is how practice can connect different musical cultures, and not how musical cultures can separate the practices. Musical culture has to be there to serve the practice, and this is one of the reasons why I am interested in curating, because I can bring knowledge of the connectivity between these different practices to bear on their presentation. Too many of the people running festivals, institutions, schools, and publications don’t have that first-hand perspective of working with the materials, so they don’t see these links and they don’t promote them. Sometimes they might dare to bring seemingly incompatible traditions together for isolated encounters, like Persian or Indian classical musicians and a contemporary chamber ensemble. These things happen every so often, but more often than not they are doomed by the gesture of making some sexy cocktail of presumed others. What we try to do in our series is to explore the continuities that are already there but may be hidden from view by our own presumptuous music-cultural frameworks.

5. Artistic Research – A Tension between Theory and Practice

This brings us to the last question: the walls that exist between the academic world of the university and that of actual practice. Music practitioners are excluded from higher education and research institutions, or more often do not want to be associated with them. But at the same time, they are not completely out of them these days. It seems to me that you are in a good position to say things about this.

Well, I am lucky to have one foot in academia and one foot out, so I don’t have to choose, at least at this point. I have always been interested in research, and obviously I’ve always been interested in making music for its own sake. In my doctorate I developed a strong taste for the interface between the two.

Then, the notion of artistic research is important to you?

Yes and no. The contents of artistic research are important to me, and I am very fond of the idea that practice can do things for research that more scientific methods cannot. I am also fond of the potential that artistic practice – particularly experimental music – has for larger social questions, larger questions around knowledge production and dissemination. I am also interested in using research to step outside of my own aesthetic limitations. All of these things are inherent to artistic research, but on the other hand, I am ambivalent about the discipline of artistic research and its institutions. The term “artistic research” suffers a lot of abuse. On the one hand, the term is common among practitioners who cannot really survive in the art or music world, because they don’t have the skills or the gumption to live as a freelance artist. On the other hand, there are academics who colonize this area, because they need a specialism. Perhaps they come from philosophy or the social sciences, art history, musicology, theatre studies, critical theory, or the like. For them, artistic research is another pie to be sliced up.

Yes, I can see.

So, there are conferences and journals and academic departments, but I can’t determine if or how many people in the world of artistic research really prize practice as practice. You can probably sense my allergy to this aspect of artistic research – sorry for the rant! Let’s just say I care less about promoting or theorizing artistic research as a discipline, and more about doing it. I suspect most of the people who do the best work in the field feel the same way. This topic has been more in my mind lately than it ever has been, first of all because I’d like to have some sort of regular income; this freelance artist hardship number is getting tiresome!

Indeed, the relationships between the different versions of artistic careers are not entirely peaceful. Firstly, independent artists, particularly in the field of experimental music, often consider those who are sheltered in academic or other institutions as betraying the ideal of artistic risk as such. Secondly, teachers who are oriented towards instrumental or vocal music practice often think that any reflection on one’s own practice is a useless time taken from the actual practice required by the high level of excellence. Thirdly, many artists do research without knowing it, and when they are aware of it, they often refuse to disseminate their art through research papers. Many walls have been erected between the worlds of independent practices, conservatories and research institutions.

Well, in terms of just the limited subject of improvisation, more and more people who can do both are in positions of power. Look at George Lewis: he’s changed everything. He paid his dues as a musician and artist, and he’s constantly doing interesting stuff creatively; and meanwhile he’s become a figurehead in the field of improvisation studies. Through his professorship at Columbia University, he’s been able to create opportunities for all kinds of people and ideas which might not otherwise have a place there.

At Columbia University (and Princeton), historically, Milton Babbitt was the figurehead of the music department. It’s very interesting that now it’s George Lewis, with all of what he stands for, who’s in that position, who’s become the most influential intellectual and artistic figure in the department.

You did your PhD at Leiden University[5]. It seems to be a very interesting place.

Yes, for sure. There are lots of interesting students, and the faculty is very small – it’s basically Marcel Cobussen, Richard Barrett (my two main advisers), and Henk Borgdorff, who is an important theorist of artistic research. My committee chair was Frans de Ruiter, who ran the Royal Conservatory in The Hague for many years before founding the department in Leiden. I believe Edwin van der Heide, a sound artist who makes these big kinetic sculptures and lots of sound installations, is also involved now. It is a totally happening hub for this kind of stuff.

Concerning my search for a more stable position, I am sure something will pop up, I just have to be patient and keep asking around. Most of these kind of opportunities in my life have happened through personal connections anyway, so I think I have to keep my hands on the wheel until the right person shows up.

Our encounter is ending, because I have to go.

Thank you very much for this nice meeting.

1. 2010 Markus Miessen, The Nightmare of Participation, Berlin: Sternberg Press

2. See Lawrence Halprin, The RSVP Cycles: Creative Processes in Human Environment, G.Brazilier, 1970. RSVP cycles are a system of creative and collaborative methodology. The meaning of the letters are as follows: R = resources; S = scores ; V = value-action; P = performance. See en.wikipedia.org

3. Alison Hirsch, City Choreographer: Lawrence Halprin in Urban Renewal America, University of Minnesota Press, 2014. (https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/city-choreographer)

4. “Ausland, Berlin, is an independent venue for music, film, literature, performance and other artistic endeavors. We also offer our infrastructure for artists and projects for rehearsals, recordings, and workshops, as well as a number of residencies. Inaugurated in 2002, ausland is run by a collective of volunteers.” (https://ausland-berlin.de/about-ausland)

5. See Leiden University – Academy of Creative and Performing Arts.(https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/humanities/academy-of-creative-and-performing-arts/research)

Christopher A. Williams (1981, San Diego) makes, organizes, and theorizes around experimental music and sound. As a composer and contrabassist, his work runs the gamut from chamber music, improvisation, and radio art to collaborations with dancers, sound artists, and visual artists. Performances and collaborations with Derek Bailey, Compagnie Ouie/Dire, Charles Curtis, LaMonte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music, Ferran Fages, Robin Hayward (as Reidemeister Move), Barbara Held, Christian Kesten, Christina Kubisch, Liminar, Maulwerker, Charlie Morrow, David Moss, Andrea Neumann, Mary Oliver and Rozemarie Heggen, Ben Patterson, Robyn Schulkowsky, Ensemble SuperMusique, Vocal Constructivists, dancers Jadi Carboni and Martin Sonderkamp, filmmaker Zachary Kerschberg, and painters Sebastian Dacey and Tanja Smit. This work has appeared in various North American and European experimental music circuits, as well as on VPRO Radio 6 (Holland), Deutschlandfunk Kultur, the Museum of Contemporary Art Barcelona, Volksbühne Berlin, and the American Documentary Film Festival.

Williams’ artistic research takes the form of both conventional academic publications and practice-based multimedia projects. His writings appear in publications such as the Journal of Sonic Studies, Journal for Artistic Research, Open Space Magazine, Critical Studies in Improvisation, TEMPO, and Experiencing Liveness in Contemporary Performance(Routledge).

He co-curates the Berlin concert series KONTRAKLANG. From 2009-20015 he co-curated the salon series Certain Sundays.

Williams holds a B.A. from the University of California San Diego (Charles Curtis, Chaya Czernowin, and Bertram Turetzky); and a Ph.D. from the University of Leiden (Marcel Cobussen and Richard Barrett). His native digital dissertation Tactile Paths: on and through Notation for Improvisers is at www.tactilepaths.net.

From 2020-2022 he is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz.

Cecil Lytle

Encounter between Cecil Lytle,

Jean-Charles François and Nicolas Sidoroff

Lyon, August 3, 2019

The pianist Cecil Lytle came to Lyon in August 2019 for a friendly and touristic visit. Cecil Lytle was Jean-Charles François’ colleague in the Department of Music at the University of California San Diego during the 1970s and 1980s. For the past few years, as part of a program organized by the University of California, Cecil Lytle taught a course on jazz history in Paris every summer. A visit to Cefedem AuRA took place on August 3, 2019 in the company of two members of PaaLabRes: Nicolas Sidoroff who teaches at this institution and Jean-Charles François who was its director from 1990 to 2007. We discussed the history of Cefedem, the nature of its project focused on the development of unique curricula, and also the constant institutional difficulties that this institution had to face since its creation. Following this guided visit, the three musicians met with a view to publishing the transcript (based on the recording of this session) in the third edition of paalabres.org, « Break down the walls ». Throughout his musical career, Cecil Lytle has refused to limit himself to a single aesthetic. He has been very insistent on combining several traditions in his practice. Moreover, his important influence in the functioning of the university has allowed him to develop actions in the field of education for the social promotion of minorities in the United States from disadvantaged neighborhoods. The beginning of the interview focuses on a meeting between Cecil Lytle and Nicolas Sidoroff to get to know each other. The latter’s artistic practice is discussed, before aspects more specifically related to our guest in the field of arts and politics.

Summary :

1. Introduction

2. Cecil Lytle, musician at the conjunction of several traditions

3. University and the Preuss School

4. A Secondary Education School in a Neighborhood

5. The Walls and Pedagogical Methods

6. The Walls and Musical Practices

1. Introduction

Before we start, it might be good to for you [Nicolas] to say few words about yourself. Nicolas was just in New York last month. So now he knows perfect English. [laugh]

No… is it my accent [laughs]? I went there with French students, who did not speak English, so I always had to go from English to French and French to English.

That’s how we are in Paris. We start to say something in French and they switch to English.

I had already been once in Boston and New York, and that time I spoke a lot in English for two weeks. My English had significantly improved. Last month, for one week, it was mostly French!

So you went there to do what?

I am a doctoral student at the Paris VIII University and I work on music and the division of labor in music, in an Educational Sciences laboratory. We have formed a collective of students from this university, to stick together, to be collective in our research and to try to shape the university according to our experiences and ideas. And we made a proposal for a symposium on the idea of re-imagining higher education in a critical way. It was held at the New School in New York. Sandrine Desmurs who works at Cefedem AuRA[1] also came with us to present the mechanisms that we have put in place at Cefedem. I also attended a lot of concerts, and I took the opportunity to meet as many musicians as possible, like George Lewis, William Parker and Dave Douglas for example. I also work part-time at Cefedem with the students of the professional development diploma program for already on-the-job music teachers. And in the other part of my time, I play music, I conduct research, notably with the PaaLabRes collective, and I’m also a PhD student in Education Sciences.

So you make music, you are a performer?

Yes, I play mainly in two collectives: one I call post-improvisation, a type of music called downtown[2] – Downtown II – do you know this term?

I know the expression. It comes from George Lewis?

Yes. The expression has its origin in New York, but a lot of people play this downtown music and don’t live in New York.

I bet you.

And it’s the second generation of downtown music, which is called Downtown II, of which John Zorn is one of the important figures and also Fred Frith, to take the most famous ones. That’s just one of the two streams of music that I do. The other one comes from Réunion Island, an island in the east of Africa, south of Madagascar. In the small islands in that part of the Indian Ocean there’s specific music called maloya and sega. And I’ve been playing this music with Réunionese people for about twenty years now, mostly on trumpet.

Now, is that what is called in France ethnomusicology?

No, it is a practice that we call traditional music, but it is above all a live culture, it is not a music of the past, but of today.

And maloya is quite specific, because it’s a music that’s been banned for an extremely long time.

By the colonials?

Yes. By the French colonials.

The French are still there. [laughs]

This music came to the forefront in the 1970s thanks to the communists and the independentists. It was at the same time that reggae also made an international breakthrough. And that’s when what’s known as malogué or maloggae (a mix of maloya and reggae) developed[3] and seggae (sega and reggae) It has become a kind of very contemporary mix of traditional music, popular music and modern music. So I play with a family who came to France thirty years ago. I was playing this malogué, séga and seggae music with notably the father who sang, played bass and led the ensemble, and his son who sang and played drums. He was not yet 18 when I met him. And he was about ten years old when the malogué was created, he couldn’t reach the bass drum pedal! [Laughs] Today, the group has reconfigured itself on a roots reggae basis, it’s called Mawaar.[4] It means « I’ll see » in Réunionnese and a good part of it is sung in Creole. And we’re still working on the music from Réunion Island, even though we don’t play it live on stage any more. The father I was talking about is on bass, and it’s the son who is very active. He plays guitar and drums, he sings, he’s one of those who contributes the most to the music.

Do the people on that island speak French?

Yes, and Creole. A very nice Creole.

You have been to that island?

Yes, but only for a week, because the Cefedem has developed a music teachers’ training program in Réunion Island. And I was able to observe the three different Creole languages: the first one, the French in Metropolitan France can understand it, even if some expressions are not French, they are still understandable; the second one is mixed, the French understand some words but not everything; and the third one, the French understand nothing.

[laugh] You just play the music. [laugh] Yes. So how did you get interested in that island, that one place?

Because of the people I met.

Here? They live in France?

That’s because I met this family, and very soon I enjoyed talking and playing this music. I have to say that I make music in situation: I met people who are very interesting and know a lot of things about this island, its history, its music and about their origins, etc. So, I’ve shared their life, spent time with them, especially by playing music.

It is very important meet people where and how they are, to stay with this people, to eat their food, to hear their stories, how do they cry, how they are happy, how they are sad. There is a pianist living in Paris, Alan Jean-Marie from Guadeloupe. He plays jazz, regular straight-ahead traditional jazz. His jazz playing is so infused with the songs and sounds from Guadeloupe, traditional folk songs in jazz version. That’s what people do with jazz worldwide – – they make it their own. He sings in Creole, very interesting. He is not a great singer, but he is very soulful, very spiritual. Let me ask, how often do you go to the island?

Just this time, and only for one week.

Oh! It is not enough.

Quite insufficient! Besides, it was really special in this story. I went alone, without this family and the current band, with very little time at hand. It became like a joke between us: yes, I was going to discover music played there right now, meet musicians who live on that island… They weren’t happy that I could do it without their presence. That’s the way life is. But now I can see that I’ll have to go back. So we’re working more intensively on the project of going there to play music together and discover this island with them.

It is very courageous. I mean, it is courageous to study something that the West has not heard before so much.

It’s a practice that comes from the streets, outside the walls of the university. We can look at it in terms of the epistemologies of the South, starting with the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos. He is Portuguese and is involved in the adventure of the World Social Forum. He has worked in South America, studying subordinate and dominated communities, how they organize themselves and how they use and produce knowledge not recognized or considered by the colonizers and Westerners. And he coined the expression « epistemologies of the South ». And it’s very interesting to observe how, now, more and more work at the university is asking these kinds of questions: the domination is still that of the objectivity of whites, of the North, of the West…

There is some interesting work being done in literature – some of our old colleagues in critical studies… Sara Johnson, who is on the faculty of the Literature department at the University of California San Diego, has been writing about cultural transitions from Caribbean and New Orleans. And in fact, I have my music students reading chapters from her book about island tastes and cultural practices–not music so much, not about the music. But some of the class distinctions persisted when the French left, when the colony ceased to exist.[5] Black classes emerged from the indigenous culture, the middle class, the military, and they started behaving like the French [laugh], very aristocratic and the core people fled to New Orleans, to Charleston or to Atlanta, to the Southern States. And then, she has just been writing from socio-literary point of view. Truly, Sara’s point is not about written literature, but oral literature. And there is obviously more and more written literature emerging since independence, but she is tracking the stories, the legends, the tales. So her work tracks cultural progressions taking place that measures closely with trans-cultural effects in music. And, all of these stories are set to music, they don’t talk about it, they sing about it, they dance it.

2. Cecil Lytle, musician at the conjunction of several traditions

Should we start the formal interview?

Ah! OK.

So, maybe to begin with, can you explain a little about who you are, what were your adventures in the past?

I am Cecil Lytle, I am pleased to be here to talk with friends who make music and make friend with people who talk about music. My initial music… How I got involve in music? My father was a church organist, Baptist church organist, he played gospel music. Also, I am the last of ten children, I have nine brothers and sisters. So all of us were in the church all the time, Pentecostal Baptist Church, five days a week, nights a week.

Where was that, in New York?

In Harlem. So it was not religion as much as it was the music that influenced me – – maybe they are the same. I don’t think that my father and mother were very fundamentalists. They just thought it was something useful for the children to do. For there were lot of bad things for children to do. We were all in the church, in the choir, we did all that. My father played the Hammond B3 organ, and right next to him was a broken down Mason & Hamlin baby grand piano. So, I am told that, when I was five years old or so, I used to sit at the piano. What is that? I think it was the happiest music I ever made [bangs his hands on the table] with the palms of my hands, and the choir… These were not professional musicians, these were women who cleaned the streets and men who worked as postal workers, so they were not trained musicians. But the power of hearing a gospel choir right in your face! You had to appreciate the mingling of their song, sweat, and dancing while praying for salvation here and in Heaven. I was too young to fully appreciate the power of imagination of African Americans, but I knew that something magical was occurring three feet away from me, and I wanted desperately to be a part of it. they sang about misery and happiness in the same breath. So it was… That every Sunday was a magical moment when these people could feel their pain, power and agency. When they left the church they were back to the real world, but it was a very special few hours when a hundred people, hundred and fifty people, could share power. Now they all knew what happens when you leave the church, when you go back home, to go back to work, they knew that world still existed. So I always remember that joy, the power of this moment – those three hours together one day a week. And I always wanted to create that more, everyday more. The challenge for me was how to do that wherever I might be in the future.

I had proper piano lessons by the time I was eight or ten years old. My father got money – enough money together to send me downtown to a piano teacher. I don’t know how my father found out about this fellow, but he was a recent Russian immigrant to New York, a Russian Jewish. He spoke no English, I spoke no Russian. So for one year he had me play on the lid of the piano, to begin with the finger stroke. I guess that’s how they do it in Russia. Just finger strokes, may be for six months, I just played on the lid of the piano. It made no sense to me, but I understand now what he was after…, now [laugh]. I thought that my father should pay him half as much. But it gradually started to make sense. About the same time, I think I also started hearing classical music. My father used to take me to Carnegie Hall, different kinds of places around New York to hear pianists. I remember he took me to hear Wilhelm Kempff, the German pianist, he played the Hammerklavier Sonata and I could remember the power of that piece, this crazy piece, it went on forever, the Fugue! I just thought it was fascinating. Everyone thinks it is fascinating. So I started to mix my gospel jazz music with trying to play Beethoven’s sonatas – -imagine that! And I think I tried to do both ever since, traditional, classical music and improvised music at the same time. Years later at Oberlin Conservatory, I think my most important musical experience was early years in the church, and it was because of the authority and the legitimacy of those untrained Gospel singers – their sound, legitimacy.

I imagine that you experienced something like that on the Réunion Island. People had no training in music or the arts, but it was powerful. They would communicate and said what they had to say. I think that what came out of all my music to say that. To feel that way. Then I met Jean-Charles François and other very interesting people who improvise in different ways, who improvise with a very different language. The goal was the same, but the language, the vocabulary was different. And I found that fascinating to enter the realm of someone else’s musical legitimacy – – to appreciate what was important to them… Music that was out of reach.

It was a very short step from gospel music, to jazz- – it is the same music, it changes the words, it changes its limitations, but all the chords are identical. There is this new movie about Aretha Franklin – I think it’s called Amazing Grace, it just came up this year – it follows her from church, gospel music to her career in Soul. It is all the same sound, and the same authority, same power.

By the time I was fifteen, my older brother Henry played drums, jazz drums, so we had a jazz trio and played around New York, a bit. It’s kind of odd, but the more I moved in the jazz world, the more I felt uneasy – -I didn’t want to spend a life as a jazz musician. I saw the life of the jazz people I met. There was one incident that turned my head around. I was once playing at the Savoy Ballroom with a large dance band backing up Arthur Prysock. While we were playing, this guy kept coming up to me at the piano saying, “Hey, man, let me play the piano, let me play the piano”. He wanted to sit in. I told him to talk to the band leader. So I’d play another number, he comes back: “Hey man!” – I was fifteen years old or so- and he was an older guy – “you can’t play that stuff, let me play the piano, let me play the piano.” So, anyway, when we took a break, I went to the band leader and said: “Who is this guy? He is bugging me, you know!”, and the band leader said: “Oh man! Don’t worry about him, he’s a junkie, that’s just Bish.” It was Walter Bishop J., a great pianist, a famous jazz pianist. I had his records at home. But he was strung out on heroin, he was all messed up in his head and body, and it hits me: “do I want to round up doing that?” A fifty year-old guy asking a fifteen year-old for a job. I did not sour on jazz, but I did not want to be dependent on a jazz life. And I wanted to play other music too. So I think the church experience and at least early jazz gigs that gave me more questions than answers. I knew from the church experience that I wanted to play music that had authority and meaning, but at the same time I wanted to do a lot of different things, not just gospel music, not just jazz, not just be-bop, and not just one thing.

So when I met Jean-Charles, I was directing the University Gospel Choir (at the Univesity of California San Diego), and we were playing New Music concerts together. I think the university gave me an opportunity to do all the things I wanted to do. If I was just playing night clubs, I would get bored. So just playing Beethoven’s Sonatas, I’d get bored… We did Stockhausen’s Kontakte, which was fun… So that’s kind of how I think about music, I don’t think that my expectations from those early experiences has really changed much, I don’t think. The authority of the music I heard as a child, the variety of music I was introduced early on, they sort of stuck with me.

3. University and the Preuss School

You were recruited by the University of California San Diego to conduct the Gospel Choir and to develop a jazz program, but later you also became the pianist of the department beyond the different aesthetics?

I thought I was hired for the Black Music, and we did just concerts and lectures. I don’t really remember what specific job title was. But then we played the concerts and it was fun, we leave a rehearsal and we talked, and I went upstairs and I do the Gospel Choir, and there is Carol Plantamura, we would rehearse lieder, there was plenty of variety. I guess my history isn’t a straight line – – my history is a mystery, I like that! But that was during the old Third College days at UCSD, when Third College was considered to be the “revolutionary” part of the University. And in many ways, it was. It was the “third” of what became six colleges. And the Third College was founded in 1965 with the original concept to be a college dedicated to Greek Antiquity. And then, Martin Luther King was assassinated, Bob Kennedy was assassinated, riots, protests and anti-Vietnam protests. Students became aroused and asked, “Why are we studying Greek antiquity when history was being made in the streets of America now?” So, the students changed the direction of the college to be more progressive – I try not to say left wing because I don’t know what that means anymore – but to be more politically active. And the leaders of were one professor, Herbert Marcuse, and his doctoral student, Angela Davis who was finishing her PhD in anthropology. She has written about this period in her life and in the life of the new University of California campus in La Jolla. She was sort of the spoke person for the students, and Marcuse the spoke person for the faculty, both moving the College in a more progressive direction. The name that the students gave for the College was “Lumumba-Zapata” College. Do you remember the name Patrice Lumumba, the assassinated President of the Congo? And Emilio Zapata the Mexican revolutionary? It was never named that formally, but some older alumni still called it Lumumba-Zapata College.

And because nobody in the administration wanted to name this college that way, it was named “Third College”, just because it was the third one in existence.

Hell, the faculty didn’t want Lumumba-Zapata. Parents couldn’t imagine sending their precious son and, especially, daughter to Lumumba-Zapata College. They were rightly afraid that we were going to make them political revolutionaries… That was not going to work. So the University said: “No bullshit! No Lumumba-Zapata! We will call it ‘Third College” and used that official name for the next 20 years.

In 1988, 52 of USCD’s performers and composers went to Darmstadt. I became Provost of Third College the week after we returned from the Darmstadt Music Festival. This post was very meaningful for me, because it gave me a platform to do things that I thought were in the interest of justice, working on opening the walls of the university. So, the first issue I tackled was finding a meaningful name for the College, not leave it with a number. What I wanted to avoid was that, when someone would ask “Where do you go to school?”, one would not answer “I go to number three!” We tried “Third World College”, not really… So we did finally give the college a meaningful name, again. Thurgood Marshall College was rebirthed in 1991. A name clearly associated with social justice and progressive attitudes about race and class relations, and until it changes again, it is still Thurgood Marshall College.[6]

Can you tell us who is Thurgood Marshall?