The Tale of the « Tale »

Louis Clément, Delphine Descombin, Yovan Girard, Maxime Hurdequint

Edition and page lay-out: Jean-Charles François

March 2024

The four protagonists have collaborated to a spectacle entitled “Le Conte d’un future commun” [The Tale of a Common Future] with:

Louis Clément, project instigator, public participation and drawing animation.

Delphine Descombin, storyteller.

Maxime Hurdequint, drawings.

Yovan Girard, music.

The texts are the result of four separate interviews with each artist during 2023, by Nicolas Sidoroff and Jean-Charles François.

Summary :

1. Delphine’s story

2. Architecture’s studies, Louis and Maxime

3. Delphine’s journey to Africa

4. Yovan Girard, the musician.

5. Delphine’s return to France

6. Maxime’s hesitations between architecture and drawing.

7. Yovan ‘s Story (continued)

8. Delphine’s story (continued). Trapeze and storytelling.

9. Louis and Maxime’s stories (continued)

10. Yovan’s Story (continued), the project « A Violin for my School ».

11. Delphine, the Tale of the Skull and the Fisherman.

12. The little notebook with trees. Maxime Hurdequint, Maxime Touroute and Louis Clément.

13. Delphine’s story (continued). The Tale of Tom Thumb.

14. Delphine and storytelling. Maxime and architecture and drawings. Yovan and composition.

15. The Live Drawing Project

16. Delphine : Two tales.

17. Origin of the “Tale of a Common Future”.

18. The AADN immersive project.

19. The “Tale of a Common Future”.

20. Louis, One Year to Reflect.

21. The writing of the Tale. Louis and Delphine..

22. The drawings and their animation, Louis and Maxime..

23. A traditional music of the future?

24. Music elaboration: pre-recorded or live music. Louis and Yovan.

25. Music and storytelling, Delphine et Yovan.

26. Music and storytelling. Louis et Yovan

27. Yovan’s ideas on music and Maxime’s ideas on drawings.

28. The Tale and drawings. Delphine, Maxime et Louis.

29. Sonorization

30. Communication with Notion.

31. Residencies: LabLab, Chevagny, Vaulx-en-Velin, Enghien-les-Bains.

32. Public participation.

33. The artistic and cultural education residency at Hennebont. Louis, Delphine and Yovan.

34. The residencies (continued): Paris, Nantes.

35. Ecology. Delphine.

36. Conclusion

1. Delphine’s Story

Delphine:

Where does the Tale come from? It’s by telling the Tale that we’ll arrive at the Tale… The Tale comes from when I was in high school and I met Marie Jourdain, the daughter of Marie-France Marbach.[1]

During high school, I was at boarding school, she was telling me stories all the time. I met her mother and Geo Jourdain. And I loved these people who were completely different from what I had as reference in my family. They woulod take me to school, to the boarding school on Sunday evenings and would bring me back on Friday evenings. I spent a lot of time with Marie, who talked to me about Africa, who told me a lot of stories. After that, I left high school and went to Africa. There, I heard lots of stories, lots of tales. And then, when I came back from Africa, Marie-France absolutely wanted me to tell the story of my trip. And I didn’t want to, I didn’t want to talk, I wasn’t at all ready to talk in front of people. She took me by surprise, and I often attended her performances. She gave me the opportunity to go to workshops, she really believed in me, when I really didn’t. So, I stayed in close contact with Marie-France.

The boarding school was in Louhans, it was a visual arts school. It was the only high school that accepted me because I had very bad marks, and I wasn’t following school at all. It was my aunt who found this high school that was willing to accept me. I stayed outside. I didn’t go to classes. I was under the trees listening to the birds, I wasn’t in the mood to be locked in a class. Often, the director summoned me, and we had some very interesting philosophical discussions. So, it was as if he had me join the 12th grade philosophy course. Then, he’d ask me what I wanted to do later in life, and I’d say: “I don’t know, maybe take care of goats, perhaps…” I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but it’s true, these were important questions that nobody had ever asked me before. It’s true that I had the chance to meet some special people. And I really liked the visual arts courses. There were two visual arts teachers who were amazing, they took us to Lyon to see exhibitions, we even went to Strasbourg to see museums, it was great, so these were the courses I attended, I was allowed to create things. As for the rest of the courses, I really rejected them, yeah, they bored me a lot. That’s why afterward I took my backpack and I got the desire to go to Africa. The journey lasted quite a long time because I stopped along the way, I didn’t have any money. I worked as a seasonal worker, in hotels-restaurants, I was doing services and they provided lodging at the same time. I sold croissants, I worked in bakeries, I did all sorts of jobs. And then, I met someone in the street who was spitting fire, who taught me how to do it. This was my first real job: we’d spit fire, I’d spit fire and then I’d beg. In fact, I’d blow bubbles in front of a bakery, telling poetry. I hated all this, I found it unbearable, but I always managed to do something.

2. Architecture Studies, Louis and Maxime

Louis:

My background story starts on December 23, 1986. I don’t know how far back I can go, but I think my parents are no strangers to what shaped me. So, I think that if we go back very far, one could say that what shaped me was the discovery of reading, and then above all the reading of what we call imaginary fiction, anything related to science fiction, fantasy, etc. And then, from a more professional point of view, or in any case in terms of my studies, I passed a scientific baccalaureate, then I studied architecture at the Paris-Val de Seine architectural school and graduated from it. At the end of my Licence, I started to realize that architecture wasn’t really for me. In fact, I already had the somewhat utopian idea that becoming an architect would enable me to conceive of spaces in which people would feel good and above all that it would help them to think, to change the world.

Maxime:

My cousin Louis Clément also studied architecture. We’re a year apart, and we didn’t do that in concert, we went our separate ways. I was at the INSA in Strasbourg and he was at the Val de Seine in Paris, we followed our own path. This was a period in our lives when we saw each other less often, but we talked a little about architecture.

Louis:

And then I was confronted with the Master and with the realities of construction, the fact that, if you become an architect, you become a builder. You work in more or less big firms, and ultimately your work is extremely determined by budgetary considerations. And so, I thought that it would not interest so much. Even so, I did my Master’s first year in Antwerp (Belgium), it went fairly well, and I was already starting to think a little that I was going towards performing arts, scenography, etc. And then, in my Master’s second year I sort of eeked by, but I got the diploma all the same. Then I had the chance to work for an architect, I did my Master’s internship at “Scène scénographie”, which is a very good enterprise. We worked on the scenography of the “Musée d’Alésia”, the “Grotte Chauvet II”, so I had the chance to count the stalactites for many hours, this was enormously interesting! Interesting but… It was fun in any case, to work on beautiful projects.

Maxime:

During the last year of high school, I applied to an architecture school, it might have been in Lyon or Grenoble, I went there with my hands in my pockets, thinking: “To be an architect is a trade that you learn, so I’m not going to learn it beforehand!” I crashed, and my only solution was to go to a preparatory school. So then I was in the first year of a preparatory school.

Louis:

And then, when I started to work as an architect, I got a job with François Pin who is an architect who also run a music festival in quarries, in the “Carrières de Normandoux[2], and he created the Marbrerie in Montreuil (a suburb of Paris). I worked on the Marbrerie project, which was one of the biggest projects, the most interesting that I could do as an architect: it was a multi-programmatic project, with an artist’s residency, a swimming pool, a restaurant, an architecture agency, a performance hall, and furthermore I was in charge of sketching it. So, I could have really been very happy, and I stayed almost six months. In fact, it didn’t make me happy at all, so I thought that, if I was not happy there, then I didn’t see what I was still doing in architecture, because, I thought I wasn’t going to find a more interesting job.

Maxime:

With Louis, my cousin, we influence each other, maybe because we know each other very well. That is to say that when we grew up, we saw each other on a regular basis, we never really lost touch. So, this is the reason that it’s always a fluid relationship between us, we never yell at each other, in fact we don’t really need to. I think we adjust one another perfectly, that’s how we influence each other. I imagine that, as we both studied architecture, we speak the same language, it helps us to communicate of certain concepts, I don’t need to explain to him such and such architectural project.

3. Delphine’s journey to Africa

Delphine:

It took me a year, from the age of 17 to 18, to collect enough money for my trip to Africa. I worked during the summer and winter seasons. In any case my mother wouldn’t allow me to cross the border. So, when I turned 18, I immediately crossed the Spanish border. At 18 I no longer feared being prevented from doing so by send police. In fact, I’d already been arrested at police stations, and they were tracking me, they track street people, they have their photos, and they know where they are. They knew I lived on the street, that’s funny, because they didn’t know this until they arrested me.

I went all the way down to Spain. I took the boat in Gibraltar, I arrived in Morocco, and then I went down to Mauritania, and on to Dakar in Senegal. After that, I really wanted to go to Burkina Faso, because I’d met some Burkinabe in France and I wanted to go and visit them, they were dancers and percussionists. So, I took the train to Bamako, Mali, where I took another train to go to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, it took 48 hours by train to get there, it’s very long. Then I went to Koudougou, they lived there. I stayed there for a while, I was there for a year and a half.

At one point in Africa, I asked myself what exactly I was doing there? What’s the purpose for me to be there? I was white, so, in a subtle way, I didn’t seem to be living there, – look, I wasn’t a tourist! – but I was there, and I didn’t have much to do there, I could simply let myself live, live with the people, but I had the impression of having a real dilemma in my head. We had great discussions, it was super cool what I went through intellectually. For example, in Burkina Faso, we were there drinking tea and talking. They’re really very interesting intellectuals, but it’s not the same kind of intellectuals as in France, we don’t come from the same thing. And in fact, I really missed Western intellectual thinking. It was also lack of books too, of this kind of nourishment, I missed that a lot. And what’s more, it also didn’t make sense for me: there were a lot of problems over there, they couldn’t sell their wheat because there was so much competition, there were societal problems.

I remember once, I was in the desert, and I heard a guy with his tiny radio, and he said to me: “Yes, I think that in your country, things aren’t going very well, there’s a man who might be elected.” In fact, it was Le Pen, against Chirac at the time. And I remember that I said to myself: “What am I doing here, when it’s over there perhaps, that the root of the problem lies?” Everything was beautiful, the landscapes were magnificent, the weather was fine, there was a very cool way of life compared to here. And at the same time, I thought: “I don’t belong here, what am I doing here?” It was a bit of a dilemma. That’s why I came back, it no longer made sense for me to be there.

Going over there saved my life, it saved my ass. When I was in France, people said that I was crazy, my family said that I was crazy, well, I was a bit lost. And when I arrived in Africa, there was that family spirit, something completely natural, I found it super sane, hyper normal. I had lots of difficulties in France, and it was not the case in Africa. When I came back to France, I was part of a bunch of friends, we were a real gang, it was a family for me, something I didn’t have before. All this bunch, they are still my friends.

4. Yovan Girard, the Musician

Yovan:

I’ve been a musician for a long time. I’m basically a violinist, so, I studied classical music and jazz. I am issued from a family of musicians, my father, Jean-Luc Girard, is a composer, he wrote a fair number of pieces, that are, let’s say, classical, but always a bit hybrid. I have the impression I am also following this pathway, in the sense that he also listened to a lot of rock, and he listened to what we played. He liked composers who were a little extraterrestrial, like Frank Zappa (I don’t particularly like Zappa), he always made us listen to plenty of different kinds of music, he wasn’t an ayatollah of jazz or rock, he was quite open-minded. My brother, Simon Girard, is a trombonist, and we’ve always played together. Simon and I had a band, and we played together in a fair number of groups. Simon’s very much into jazz, even if he’s played in popular music groups. At the beginning the connection between us was jazz. I’ve known Louis Clément since early childhood. Louis’ parents, Sylvie Drouin and Dominique Clément, and my parents knew each other very well for a long time.

5. Delphine’s return to France

Delphine:

I went back to France, and I landed in Montceau-les-Mines and there I stayed for a long while. Well, already I’d fallen in love with a boy who was a stone carver and a painter, and I lived there with a bunch of friends in a house with mattresses on the floor. The problem is, when you’re settling down and become sedentary, that’s when you really become poor, because you have to pay the rent, the electricity, the water. Before that I never felt that I was poor. But there, it was really the case, I had no dough and I had to live.

Scene 1: Delphine with the woman social worker

|

A social worker: I suggest you attend a training program called IRFA-Bourgogne.[3] Delphine: What’s it all about? Social worker: It’s a training organization that helps you to try several jobs, several trades of your choice, you approach companies, and then you go. There are about twenty people in this training program, some working in funeral parlors, others in shelving, in a telephone call center, some doing housework, laundry… Delphine: … all sorts of things that didn’t suit me, I couldn’t see myself doing that. Social worker: You know, there might be other things outside that, you could go and see, I don’t know if they’ll hire you, but you can go and see… Delphine: I will try the Atelier du Coin [4] in Montceau and the Gus Circus in Saint-Vallier [5]. |

Scene 2: At the Gus Circus.

|

A guy from the Gus Circus: Hello Delphine. Delphine: Would you like to be my friend? A guy from the Gus Circus: Yes. Come, you do tight rope, you do juggling, you can come here every day, whenever you want, the door is always open. Delphine: I like it, I’ll be able to train like that. A guy from the Gus Circus: You know, the Gus Circus basically doesn’t want to hire anyone. Delphine: It doesn’t matter, I am going to stay there, it’ll work, it suits me. I have already the fiber to do that, because when I was on the street, I’ve already spat fire and juggled with balls. |

Delphine:

So, they offered me a job on a subsidized contract, it was my first job, my first long term contract, for six months. Then I stayed to teach children for maybe three years, I don’t remember exactly. I think they renewed the contract once, these were subsidized contracts for non-profit organizations (associations), something not very expensive that was 80% reimbursed by the State, so they were able to do it. An after that, they actually hired me, they figured out that having one more person brought them more children to teach, so it worked for them. So, I worked for the Gus Circus of Saint-Vallier for a certain time, I don’t even know how long…

I worked in all the disciplines: clown, tightrope, trapeze, juggling. I got the BIAC diploma [6] [Brevet d’initiation aux arts du cirqueto teach circus arts. And then, the association imploded from the inside. In fact, it was the students’ parents who were the bosses, and it went very badly, there were conflicts of interest, conflicts of power. As we were just employees, we couldn’t have a say in the matter, it was their decision, and as a result, things exploded, so my friend and me both left. And I went on a professional trapeze training with a trapezist in Moux-en-Morvan, a completely crazy trapezist, Nicole Durot [7], who did performances under a helicopter, under a Montgolfier, in a word, trapeze without security. She’s 60 years old! When she took me on in training, she was still doing that kind of things, she was a warrior. I stayed for six months with her in intensive training.

6. Maxime’s Hesitations between Architecture and Drawing

Scene: Maxime’s meeting with the Venerable Member of the Grand Council.

|

The Venerable Member of the Grand Council: Maxime, after this year in a preparatory program, how do you see your future? Maxime: I followed the program very seriously, and I came out of it honorably, but now I’m beginning to wonder. The Venerable: What interests you? Becoming an engineer? Maxime: No, I don’t want to be an engineer, that doesn’t really interest me, in fact I think that I want really to be an architect. The Venerable: Did you do any drawing? Maxime: Like all children, I used to draw, and I think I was encouraged a little. The Venerable: Can you show me your drawings? Maxime: Yes, here they are. The Venerable: Your drawings are good. Maxime: Drawing motivated me to continue. I know that my brothers were very good at drawing, but I don’t know why, it encouraged me to persist. And it’s true that as a child, my parents sent me to an art school, and I think that it does in fact eventually opens doors. I would go to that school every Wednesday for one hour, and the teacher would provide ideas for drawing, what I liked, it’s that he said: The ghost of the drawing teacher: Here we are, I don’t know, you are going to draw figures, and you are going to do it in such a way so that the feet touch the bottom of the sheet, the head the top of the sheet. Maxime: In fact, it reminded me of the Greek or Egyptian friezes, and so, I liked this idea of setting the rules of a fairly simple game, and then we would do it, and we could see that the results were all different. That’s pretty much what I retained, you fix a totally arbitrary rule for yourself, and it brings about all kinds of possible results. I would have liked to go to an art design school, there were illustration programs. The Venerable: It’s a possible alternative. Yes, it would be good for you to go into architecture. Someone passing by: Yes, it would be good for you to go into architecture.. A lady: Yes, it would be good for you to go into architecture. Maxime: Effectively I could go this way. The Venerable: It would be good for you. You can continue to draw during your architecture studies. Maxime: I’ll never give up drawing, but I don’t take it too seriously, I never thought that I would make a career of it. It’s a thing that I liked doing, and I liked seeing myself progressing, I liked looking at it, I liked sharing it. I think I was not serious about it, so that’s why I didn’t choose to study it, even though architecture is indeed quite close to it. The Venerable: In fact, you can be an excellent architect without knowing how to draw. Then, it’s interesting to know how to draw to communicate your ideas. You can end up drawing badly, but be good at drawing your ideas. Then, to be good at drawing can be useful in architecture. Maxime: Yes, I think this is going to help me, I might not be the best, but it’s a good thing that I know drawing, it will be a plus for architecture. The Venerable: Don’t be under any illusions: in the end, it won’t be long before you’re on the computer. and it’s no longer necessary to know how to draw. Maxime: Ah? The Venerable: Well, there’s a way around it: At the Strasbourg INSA you can be recruited as a student after only one year in preparatory school and they have a program of studies in architecture. I have a colleague whose son is in that school, call him! Maxime: Bingo! I’m going to do it, if I’m accepted in that school, then I won’t have lost a year and I might be with people like me who have chosen this path. The Venerable: The INSA in Strasbourg was founded during the German period (1870-1918), and at that time, the Germans didn’t distinguish between engineers and architects. So, this school has a tradition of being an engineering school, but it also trains architects, and this is something that has been kept. About 50 architects graduate every year, I think there are a little less nowadays. During the first years the courses are focused on engineering, civil engineering, and then thermic engineering. Maxime: I have no particular desire to move in this direction. The Venerable: It’s an opportunity to be seized. Maxime: It’ll enable me to be outside the classical schools. |

Maxime:

After my architecture studies at INSA, I worked in Strasbourg, I moved then to Paris where I worked for eight years. In the meantime, I had several experiences in foreign countries, I had an internship in Denmark, and one in Mexico. Then I worked for two months in Tokyo, because it was a culture I really wanted to discover, I dared to send my CV, and they told me: “Let’s do it, come if you like.” I already had maybe two or three years’ experience, so, they took me on for a two-month trial, and then there was no job available to stay. So, I came back, but it was a beautiful experience.

7. Yovan ‘s Story (continued)

Yovan:

At the beginning the connection between my brother and me was jazz. After jazz, I went a lot towards popular music, because I really enjoy composing. I’m in a rap group called Kunta, rap and Ethiopian music, with several instrumentalists. In Kunta, I play keyboard and I rap in English. In fact, I’d been doing a bit of rap on my own for a long time, and it was hard for me to imagine that you could do both playing keyboard and rap. Now I do it from time to time in certain projects, but at first, I didn’t want to mix the two, because it was a bit like two different personalities. So, I played keyboard because it was needed in the group. I simply got into playing Ethiopian scales, what you played on the piano wasn’t too complicated. Now I do both equally, keyboard and voice.

I like making different types of music, in fact I’m not locked in. I’ve already done quite a bit of music with images, notably I did music for a short film by a friend, Pierre Raphaël, and so that’s how I started. Then, I composed music for a theatre play, a modernized version of Cartouche. I’ve always been composing for a long time, doing what you might call “prod” at home on my sequencer with keyboard, plugins, it’s what my “generation” in quote does in the home studio, making the instrumentals to rap on top, but also some couplets, sometimes singing more, trying things out, in short, making music at home. That’s what we call bedroom music. I’ve always done a little of that, whether it’s rap or pop, I enjoyed experimenting because I listen to a fairly big number of different things.

|

|

Le poste de travail de Yovan

Photo: Nicolas Sidoroff

Scene 1, Yovan with a stage director [8]

|

Stage director: I propose you make the music for a collection of poems by Arthur Rimbaud. You could play violin. Yovan: I propose that it be a solo violin without effects, because I liked the idea that it be as simple as possible. Stage director: I insist that there be perhaps effects on certain passages where I hear different colors. Yovan: I’ll do what you ask me to do. I like to start with a simple idea, for example just to compose for a project, but without worrying about the live music, because if you have to do live what you composed at home, it’s always complicated, unless you compose for a group. Stage director: Even so, I would like you to do straight away the multi-instrument (violin and electronic effects) live on stage. Yovan: It stresses me a bit. No, I’d rather just play the violin. I’m going to write a piece for solo violin, without anything else, rather than to have to engage myself straight away with the Swiss knife. Stage director: I nevertheless need these changes of color at certain moments. Yovan: OK, I accept, but I’ll just take a delay and a distort, because these I know them well, they do different things and can be useful. |

Yovan:

I also composed music for digital arts, for example for an artist called Minuit, Dorian Rigal [9], he makes wall projections and quite a lot of immersive things, he is invited everywhere now, in particular at the “Fêtes des Lumières” in Lyon. I’d already done illustrative music for his scenography. So, the project with the “Tale of the Common Future” is like continuing all this, to compose music with images, for a spectacle, or a show.

Scene 2, at the start of the project of the “Tale for a Common Future”. Louis and Yovan.

|

Louis: Hello. Today, we start a first two-day residency to work on the music of the “Tale for a Common Future”. Yovan: It’s not what I’d understood since the text od the tale isn’t written down yet. I prefer to compose at home beforehand. Louis: No, but anyway bring something to play with. Yovan: Listen, if you like, but it’s not exactly what’s going to happen. I have my analogue keyboard with me. I can start to play textures. Hey, here I’ve chosen one of them, this could be a starting point for the intro. Louis: We’ll talk together a lot on how we’ll proceed from there. |

8. Delphine’s Story (continued). Trapeze and Storytelling.

Delphine:

To make a living as a trapeze artist, the problem is hanging up a trapeze. I wanted to be autonomous, so I built a yurt (I have still it in my garden), in which I hang a trapeze. Then inside, I could give performances and lead workshops, it allowed me to have an autonomous job. I did this in the Morvan (because I was living in Morvan quite a lot), at La Tagnière in Saint-Eugène. The yurt, it’s something that can be dismantled and reassembled, I’ve never stopped dismantling and reassembling it for 4 or 5 years. I didn’t do performances with words, just with trapeze, impromptu performances with musicians I’d meet.

Scene between the Venerable Storyteller and Delphine.

|

The Venerable: You hang out a lot with punks. I don’t like it. Delphine: I came to see your performance with them. They like it. The Venerable: You are in a bad way! Delphine: I know it’s not the kind of crowd you would approve, but I love punks, they’re my family. The Venerable: You hang out in bars. Delphine: For me there is a very strong bond there. The Venerable: I will never abandon you. Delphine: Thank you. The Venerable: You should become a storyteller and tell the stories related to your African trip. Delphine: I am incapable of telling what I lived through. The Venerable: I propose to you to take part to the Contes Givrés Festival [10] under the yurt. Delphine: I am not at all ready to talk in front of people. I could maybe do a performance without words. |

Delphine:

It was my first performance for the Contes Givrés, it was called “Liberté”. It was a 20-minute performance on a trapeze with a guitar, under the yurt. For the first time it was really a spectacle that we’d designed, sold and performed. And that’s something that has been touring quite a lot at festivals. This brought me closer to Marie-France Marbach, so, I came back around here, I put up the yurt at la Fabrique, a place of residencies for creation in Savigny-sur-Grosne, in Messeugne. I found Marie-France there, and I lived at Pauline’s, who works with Contes Givrés. As she was going on a world tour, to spend a year in Asia, and she left me her flat, because I had nothing, I settled in there.

9. Louis and Maxime’s Stories (continued)

Scene between Maxime and Louis. Architecture and scenography, architecture and drawing.

|

Maxime: I never gave up drawing because as I progressed, even when I was working as an employee in an architecture firm, I found that projects took a long time, so you do some drawing, at the beginning you present sketches, 3D images, drawings, lots of elements like that, very beautiful that make you want to get at a result. So, this part is super, but then, for myself, I want to arrive more quickly at a result, I don’t want to make only beautiful images. And to get to a result, it takes a long time, and there are really too many obstacles that can make you fall into something different from what you want to do. Louis: For me, it was important to be my own boss, so, I said to myself that scenography for events was more indicated than working for an architect’s office, because to be one’s own boss as an architect implies lots of problems, the décennale [11], and above all I was facing the temporal unfolding of a single project which in architecture can easily take ten years. This was more what I had in mind in terms of temporality, even though now it’s really a little more than that. Maxime: I still like architecture, so I continue practicing this way, because it takes two years to realize a project, and then it’s very gratifying to go there, to make it alive and all that, but I needed to create things over a much shorter period of time. Louis: With scenography for events, I was a self-employed entrepreneur, small task person in event organizing firms. Two years later, I started to be stage manager for the Ensemble Aleph [12] and other organizations. I also discovered video projection and mapping. It appealed to me a lot and I started to do that. Then, the fact of meeting people involved in video-projection led me towards digital arts and led me specifically to the tours guided by smartphones. You have in your pocket a fairly powerful tool, which people use to do very little. I thought that it could be interesting to see what could be done with this. Maxime: I remember that during the evenings at home, on weekends, I was spending two hours to make at least one drawing that would make me happy. And my little ritual was: I would do it in the evening, and in the next morning I would put it on the floor near the window, and it was then that I had the validation, it was then that I would know if it was successful or not. So, I would get up the next morning and say to myself: “Ah! frankly not bad.” Or “No, no, I didn’t go through with it.” Or else “OK, it’s not as it should be, but on the other hand, the next time I’ll change the color, I’ll do it again differently.” And this was the big difference with architecture where in the end, if you do many tests, you never consider the final result. You work by approximation of the result and once it’s there, frankly, it’s too late. You can no longer break the walls, you can repaint things very little, so it’s pretty frustrating because you say to yourself that you were close, but that you could have changed this or that if you would have been aware of it beforehand. However, there, with drawing at home, what I like is that you are like the chefs: they have a dish, and if they want to change a flavor, an ingredient, they start the dish again and they come up with a result again. I like the fact that in my everyday life I can do the two activities, the very long work in architecture to achieve a result, and the fairly short work time an artist needs to achieve a result that itself leads to the following search. Louis: The first encounter with mapping [13], came through YouTube, with a collective called 1024 Architecture. They are behind one of the software programs called MadMapper. I discovered mapping at a Christmas tree gathering, they had basically stretched some tulle fabric on tour Layher, some construction site scaffolding. It’s amazing what you can do with just tulle fabric and video projection. In fact, what really appealed to me about mapping in the first place, it was its holograph, hologram, holographic aspect. It would take form somehow, and as such it spoke to me well with my architecture background, and the fact that it was contextual. |

Yovan’s Story (continued), the Project « A Violin for my School »

Yovan :

I’m currently teaching two days a week for a project called “A violin for my school”. Basically, it’s a social project that aims at reducing school failure through music learning, they called in neurosciences researchers to conduct a 10-year study to see how students behave. It’s an interesting project that concerns students up to age 16 taking violin lessons, sponsored by a Swiss foundation, the Fondation Vareille. In this program, there are a lot of teachers, but certainly not enough, otherwise it’s very good, the students like making music, the violin, they only play violin. The foundation bought a lot of violins for all the students. It’s good for the students do this, they are all in ZEP+ [Priority Education Zone+], which means that certain of them have complicated profiles.

11. Delphine, the Tale of the Skull and the Fisherman

Delphine:

The first story I told was one I heard from Marie-France and loved. It’s the story of the skull and the fisherman:

The Tale of the Skull and the Fisherman

|

A fisherman finds a skull there. Fisherman: Skull, what are you doing here? What brought you here? Skull: The word. The fisherman is very astonished that the skull speaks. Fisherman: Skull, you have spoken, what brought you here? The skull unlocks his big jaw: Skull: The word. The fisherman runs to the king. Fisherman: Wow! there is a skull speaking over there. The King: Wait a minute, you’re bothering me with your stories of a skull speaking there, do you think I‘ll believe you? It’s not possible. Anyway, I’ll come, but if it’s not true, I’ll chop your head off. The fisherman, he is sure of himself, he takes the king, the ministers, everyone. Fisherman: Skull, skull! Tell the king what brought you here? Skull: … Fisherman: Come on skull, please speak, what brought you here? Skull: … So, the king chops the fisherman’s head off, the head falls on the floor, it rolls and rolls, and rolls, it comes right next to the skull. Skull: Head, hey, head! what brought you here? Head: The word. |

Delphine:

And I liked this story because precisely of this fear of speaking: what is speaking? What should be said? What shouldn’t be said? Do you have the right to say anything? Are you going to have your head chopped off if you say something that you shouldn’t? Perhaps it was my fear of speaking that made me to tell that story, it was one of the first ones I used. And then, after that, what tales did I tell? I found stories, I looked for them in books, my bookshelves are full of books, I read, read, read, a lot of stories. And then, I chose the ones that touched me.

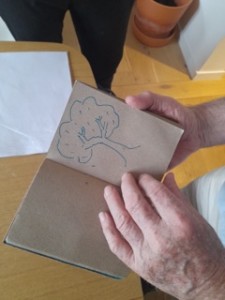

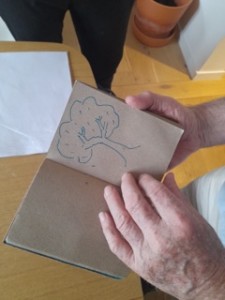

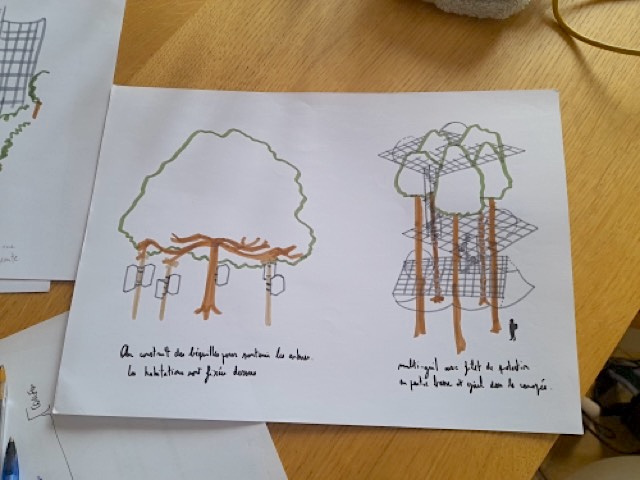

12. The little notebook with trees. Maxime Hurdequint, Maxime Touroute [14] and Louis Clément.

Scene 1: All three of them drink coffee at Louis’ home.

|

Maxime T. : I am a computer expert and I do also artistic photography projects. Here are several ones of them. And some software I have encoded. Maxime H. : Ah! Louis : Ah!… I am interested in mapping. I do it on masks. I build African mask out of papers, fairly simple things, which I then map with a video projector, adding colors. Maxime T. : Ah! Maxime H. : Ah!… Here are my drawings. Louis : Ah! Maxime T. : Ah! OK, super, but we don’t know what we could do with them. Louis : Why not tell a story? Maxime T. : Yeah… Maxime H. : Yeah… Louis : No, it won’t do. Maxime H. : I’ve also this, that’s cool and funny.. |

|

|

|

|  |

Maxime’s little notebook with trees

Photos: Nicolas Sidoroff

Scene 2, sometimes before, Maxime H. and another person.

|

Maxime H.: Draw me a tree on this notebook. The other person: Hell no, I don’t know how to draw and all that, and then, frankly, a tree, no, that’s not possible. Maxime H.: Surely you can do it, and then, if it’s ugly, in any case it will remain anonymous. As soon as you’ve finished your tree, you can look at all the other trees that have been drawn before, frankly, there are some cool ones. The other person: OK, I’ll draw a tree. Maxime H.: I find it funny to see the richness of the different trees. |

Scene 3: During Maxime’s architectural studies.

|

Maxime H.: Here we are, guys, I’ll ask you to draw a tree, and then we will hang all your drawings on the class wall with a little text I’ve written on the meaning of drawing trees. Each student draws his/her tree. Maxime H.: A student: What should we look for? Maxime H.: If there are roots going into the ground, if there are leaves or not (because many people draw trees without leaves), if the branches are going down, if the trunk is thin, if there is a hole in the trunk – it’s a great classic – and finally, there are absurd things : if there is a bird on the left branch, but looks to the right, that means something. But it’s impossible, it would never happen, A student: But it’s exactly what I’ve drawn, this thing! [General laughter] |

Scene 4: in 2015

|

A Japanese friend: Here is a present for you: a little notebook. Maxime H.: Thank you. I don’t ‘know what I am going to do with this notebook. The notebook I had before was nearly full when I lost it in the Paris metro. I’m going to do it again with this new notebook. I tried to do it with other things, like doing it with fishes, anyone can draw a fish, but the results were not very interesting. Someone suggested to draw a teapot, or a window, I tried but frankly, I never came up with anything other than a tree. Yes, it’s true, the fishes are less interesting! |

Scene 5: return to the first scene with Louis Clément, Maxime H. et Maxime T.

|

Maxime H.: It clicks! Louis: It’s great, we could do that, but we could get people to draw the tree on their smartphone with their fingers, and then we’d send it, and you could do an arboretum, where everybody can see everyone else’s trees. Maxime T.: We will call it the Live Drawing Project. |

13. Delphine’s story (continued). The Tale of Tom Thumb.

Delphine:

A friend of mine, Florent Fichot, who is an actor, suggested to me that I do something where I would tell things on the trapeze, and so, I was reciting some passages, from Peter Pan for example; it was called “Souffle court” (short breath). We played it at the Théâtre du C2 [15] (in Torcy, in Saône-et-Loire).

Then, there was the story of Tom Thumb on the trapeze. Not the story of the real Tom Thumb, right? But Jacques Prévert’s “Petit Poucet” (“The Ostrich”) [16].

The Tale of Tom Thumb

|

When Tom Thumb, abandoned in the forest, sowed pebbles behind him to find his way home, he had no idea that an ostrich was following him to eat all the pebbles one by one, “ram, ram, ram”. Tom Thumb looks back, no more pebbles! It’s a sorry state, no pebbles no house; no house no returning home; no home no daddy-mummy. Then he hears a noise, he hears music, a racket. He pokes his head through the leaves, and he sees the ostrich dancing and singing, and she looks at him. Ostrich: It’s me who make all this noise, I’m happy, I’ve eaten… Tom Thumb: You have a magnificent stomach. Ostrich: Yes, I ate lots of stuff. Come on! Get on my back, I go very fast, I’m going to take you far away. Tom Thumb: But my mother and my father, won’t I ever see them again? Ostrich: Did your mother beat you sometimes? Tom Thumb: My father used to beat me too. Ostrich: Ah! he used to beat you! Wait a minute! Kids don’t beat their parents, why should parents beat their kids? I can’t stand violence against children. Did he ever beat you? Tom Thumb: Yes, Father Thumb also beat me. Ostrich: You know what? Father Thumb is no good. And your mother, instead of buying big hats with ostrich feathers, she’d better be taking care of you. And your father, he is not very smart, do you know what he said to your mother the first time he saw her? He said: ‘she looks like a big pond, it’s a shame there is no bridge.’ Everybody laughed! Tom Thumb: I laughed, but my mother slapped my face: ‘you can’t laugh when your father says that’. Ostrich: The thing, boo!! |

Delphine:

At this point, I fell off the trapeze and broke my hand.

I think that I was taken by emotion looking at the audience. I fell off the trapeze and broke my hand, as a result I couldn’t speak anymore. The problem with working the trapeze, and telling a story at the same time, is that you have to be there with each part of the body, in the hands, in the legs, with each support point, you have to be concentrated. Except that I was telling a story at the same time, I lost focus and I fell.

14. Delphine and Storytelling, Maxime, Architecture and Drawings, Yovan and Composition.

Delphine:

My wrist was broken, I was operated on in Montceau, and they failed – you should never go to Montceau, you’ll know now – they failed me, I had to have another operation, so that lasted a year. As a result, I’d to earn a living.

Scene: Telephone call with the Venerable stroryteller

|

The Venerable: What do you intend to do? Delphine: I’m banking on storytelling. I’m going to tell stories, I’m capable of it, since I did it on the trapeze.. The Venerable: You know, it’s a sign, if these things happen to you, it might be because you have got something else to do besides trapeze. |

Maxime:

Visual arts are hyper wide in range. I don’t know if it’s a rule I’ve set up for myself, but I hadn’t explore that much outside drawing, so some of my friends told me: “Well, try to open up your practice a little.” I think it was good for me to gain confidence little by little with small formats, and gradually, I’ve become more at ease with large formats. As I’ve been doing a lot of skateboarding, and my brother makes skate art, he sculpts on skateboards, he introduced me to that, so, I did some skateboard art, I must have produced about ten of them, and then, recently, I was commissioned to do one on a big surfboard. I think it’s a question of feeling at ease, and after that, you can move on to bigger formats. What’s also amazing about skateboards is having the object in your hands, and being obliged to move with it, to move around it, whereas with the sheet of paper, it’s really only the wrist that’s moving. Here, there’s a relationship with the object, even if you’re not producing the form… I’m discovering all this gradually, bit by bit, as I become more comfortable with my artistic or illustrative approach.

Yovan:

When I compose, I often use a sound that develops in a given time. Sometimes I have to stretch it out a bit, make things longer, and sometimes a bit shorter, that’s why the repetitive side is convenient, and it’s also what you want, an electronic dimension. Normally, when I compose pieces, I have a beginning and an ending, I know where I’m going, and I like to have a little constraint especially for the music I compose for other’s projects or collaborative projects.

Delphine:

So, gently, I started telling stories and, in so doing, also becoming more self-confident. I think that you are completely naked when telling a story: slips of the tongue, tone of voice, all this tells things about yourself. I felt that it was for me a very delicate issue: being in front of an audience, being afraid of their judgment, of judging yourself. I’m very demanding, I’m very critical of myself, so I was very afraid of what I was going to experience with myself. Speaking in front of others, you’re committing yourself, committing a part yourself. I find that very risky, in fact.

Yovan:

And among the sources that have influenced me, there is a musician, actually not quite a DJ, called Débruit [17], who in particular did a project – KoKoKo! [18] – with percussionists from Kinshasa. It’s really interesting, precisely because he respects their work, he uses their music and just adds small electro touches, but doesn’t deform their music. What Débruit does inspired me well before that KoKoKo! project, but it is one of his most accomplished projects, because it really respects traditional music, and then goes for electronic touches to modernize it a bit.

Delphine:

With the trapeze, I gesticulate a lot, and as time goes by less and less, but it’s true that I move a lot, I engage my body a lot, and I work a lot with a double, often a musician. At the start, the guitarist Julien Lagrange [19] was the guy with whom I formed a trapeze-guitar duo, and he’s still participating in tale-guitar performances. That helps me a lot because we work things together, we set-up rhythm, it pushes me to work too, because when you are alone in your kitchen, you do it, but it’s less easy than when you meet someone to work with, so it helps me to be two. Often, after working on the stories with Julien, I also do them without the guitar. It’s reassuring not to be on my own, and that’s how you build things up.

Maxime:

My main activity is as an architect, but I don’t consider that drawing is just a hobby. There are times during the week which are reserved for drawing, so these two activities coexist. One is more important than the other, but as I’ve participated in exhibitions and I sometimes had commissions, I’ve also been able to sell certain works. Of course, the artistic part of my life is not the one that feeds me, but at the same time, I’ve been able to go further with it. I began by having an exhibition in a café in 2020, where I showed several drawings I’d made during and after my trip to Asia. I also made some drawings on skateboards, I’d done one tryptic and one diptych of skateboards, again in that style. In 2021, I’d an exhibition in a restaurant shared with another artist, I used the theme of the Mayas, because I’d been to Mexico. I had done for this exhibition a triptych of 3 skateboards, and a diptych of 2 skateboards with another artist working in a completely different universe. The same year I participated in a skate art exhibition in Roubaix, I sent in a diptych on the theme of Japan, some people got interested and bought it. It was very funny: a lady offered it to her husband, a former skateboarder and she said: “He is a fan of Japan, he loves skateboarding, I felt it was his style. We’ve put it in good place in our living room.” I was delighted.

Delphine:

I turned primarily to young audiences, I thought it was less judgmental. In a way, it’s harder, because if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work, that is they’re not going to pretend that it’s good. There is something about children, where if it doesn’t work, you know it straight away, there’s no two ways about it. And at the same time, there’s less judgment in relation to references, to labels, to what already exists.

Maxime :

Then we did a group exhibition in 2022 with my brother and another artist, where this time it was only skateboards that we sculpted. We decided that for each of us, there would be one skateboard we would do entirely ourselves, another that we would share with one of the other two artists, and the third would be shared with the other artist.

Yovan :

I work with Cubase. It’s not obvious, people don’t understand why. Everyone’s on Live. When I am on my computer, I don’t use Live often, in fact I never use it. It was always a bit of a struggle to say: “Well, I am on Cubase”. And during the first residency we had in Lyon, the sound engineer told me: “Ah! but I’m working on Live, you have to learn Live”, and finally he was a bit at a loss and so was I. We found a common ground and he saw that I had the latest Cubase version with the same functionalities, he understood quickly, and he showed me how to adapt the pieces in 7.1 [20] for a spatialization. I’d never done that, it stressed me a bit at first, so I said: “Well, that was an interesting thing to do.”

Delphine:

You have to be very demanding about what is told and by whom: if you tell a story that has been already told by such-and-such a person, or that comes from such-and-such a place, it might be poorly seen. For example, to tell a story that has been written by Henri Gougaud, because he’s a guy who takes up traditional tales, and puts them in his own name, you can’t do that. Or take up a story told someone else, you can’t copy-and-paste. You have to be careful with what you do, in fact, you can’t tell just anything. You have to respect everyone’s work, always say what’s the origin of your stories, from where it comes, from what country, from what culture. And as with any work, I think that as soon as you put your foot in it, the more you realize that there is work to do, it’s without end.

Maxime:

And last year (2022) we had a collective exhibition of surfboards at the Lyon City Surf Park near the Décines football ground. It was the opening vernissage of this sports facility, and they had asked 20 artists to draw on surfboards. I produced this work on Moroccan theme, because it’s quite well-known in the world of surf, I was inspired by Moroccan arts and I added the sea at the end.

Delphine:

When I speak of rhythm, it’s the rhythm of narration. Because often, there are moments when it’s almost singing, there are refrains that are repeated, and an ending. It has to grow in intensity, it has to decrease. There’s a real rhythm to the creation of a story. What is hard with the “Tale for a Common Future” is that it’s a very long story, so it’s more difficult to get into a rhythm.

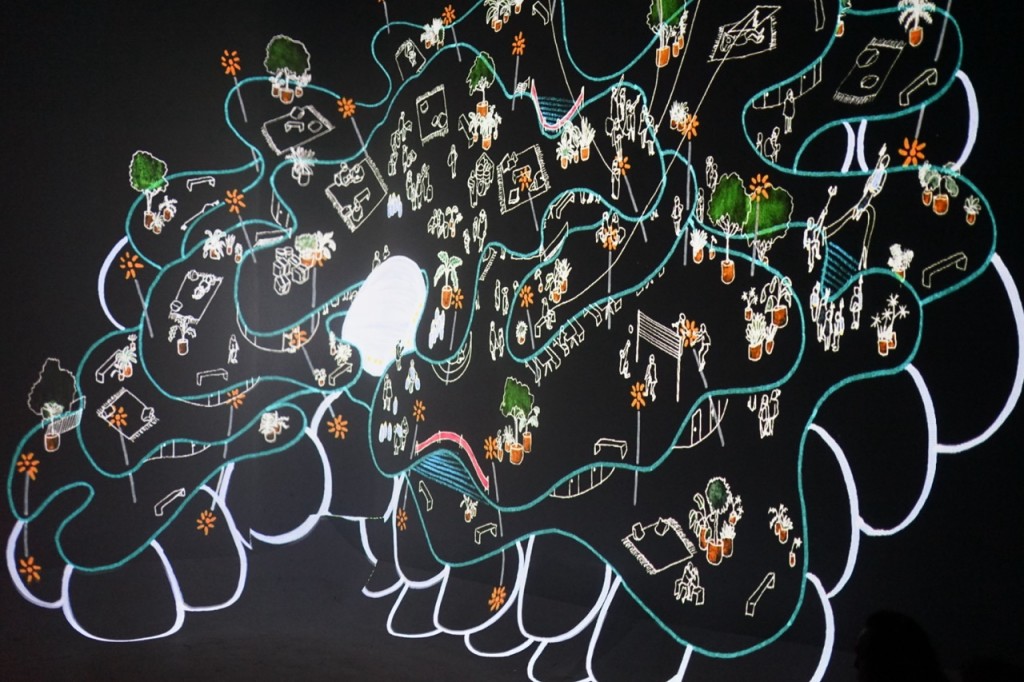

15. The Live Drawing Project

Louis:

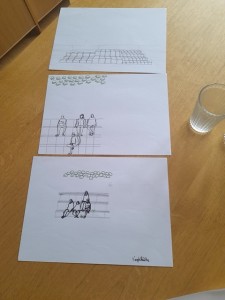

And then, I switched to video projection, and I started to design this first project that worked correctly, it was the “Live Drawing Project”, which was clearly the result of a meeting with Maxime Touroute, Maxime Hurdequin, and me. I met Maxime Touroute at a mapping workshop, he had just arrived in Lyon, and each one of us had in turn to present ourselves, and he said that he was working as a developer for Millumin. Maxime Hurdequin is my cousin, so, we’ve known each other since early childhood.

Maxime:

With the three of us, we organized a lot of working time together. At many times, even though we were working side by side, each one of us would work on our own. But there wasn’t this feeling of distance between us. With the Live Drawing Project, the heart of the matter remained the computer, it was really Maxime Touroute who coded, and then there were a lot of tasks that came into play: the communication part, the project management, preparation, set-up.

Louis:

In fact, there are three software programs that exist to do « mapping » and work very well, Resolume that I use, Madmapper which was designed by Swiss people and well known in the trade, and Millumin that tried to find a place in the performing arts.

Maxime:

It will be quite different with the “Tale of the Common Future” where the branches join together at the end during the residencies, and the rest of the time there is not much need to communicate with each other.

Louis:

And we thought that it might be to have people draw in order for their drawings to appear on a screen in real time.

Maxime:

For the Live Drawing you need to know what you are capable of doing and whether you can really encode as you go. OK, there, Louis, do you think that we will get there doing this on this interface?

Louis:

Well, no, it’s impossible, we cannot do it.

Maxime:

Hop ! So, you must have a lot more exchanges, because, the skills are much more linked together, it’s a constant ping-pong.

Louis:

And one month later we participated to the “Fête des Lumières” in Lyon.

Maxime:

During the “Fêtes des Lumières” in Lyon, it was in a bar, the Club des Lumières. The bar tender had stated: “I’ll give you 150 bucks for three days and you make me an event ‘Fêtes des Lumières’.” So we showed him our idea, I had made three drawings to explain it, and Maxime Touroute, did the coding every night for ten days, and it works very well. And what’s more, people would have enough to do, and only make one or two drawings and that’s it. We thought that when we proposed a little theme, draw a flower, draw a tree, we thought that people will have their own task at hand, and only make a small drawing, and that’s it. In fact, not at all, people get really interested, they stay for an hour drawing next to each other, saying: “Look at mine, look at mine!” And in the end, we realize that the more drawing themes we gave, the more people ideas people had, or they wouldn’t follow the proposed theme at all. I think we had found a really open tool. It’s true, we can’t deny this, that people had the tendency to look at their own phones in an individualist way, but because they were drawing right next to one another, they were also exchanging words with one another. And then there were those who didn’t draw, they looked at the big screen where the drawings were projected. We realize that when we passed between the people, things happened, people chatted, they showed each other things, it gave them ideas. We thought: “Yeah, that’s cool, we have got something there that’s rich”. That’s what we developed with Maxime Touroute and Louis, this tool, the Live Drawing Project, a project of participatory drawings that we enriched as we went along.

Louis:

And after that, it got rolling, we are now at our 140th projection.

Maxime:

With the Live Drawing project, when we use it, it’s really a big remote control. Maxime Touroute provided lots of keys: there is a key to change the color of the drawings, one to make them bigger, one to make them smaller, etc. And you can make crossfades, and things like that, but we are not really telling a story; we simply animate the images to avoid always having the same visuals, but it’s not narrative. By contrast, the “Tale of the Common Future”, with the Resolute software, and the fact that there is a storyteller, is really very narrative.

Louis:

We have been touring about everywhere in the world, it has worked super well.

Maxime:

This has been going on since 2018 until now. We had other gigs in 2019 and 2020. It became gradually better remunerated; we were able to buy a video projector, get an association to take care of the administrative side. So, little by little we became more professional. We travelled to Canada, to Denmark. Then there was the Covid confinement, so we developed tools specially for the confinement, by organizing remote communication events. This was for us a good source of revenue, we did it again with Denmark, this time in tele-conference. We are present in many countries, lately in Burma for example.

Louis:

And I told myself at some point that I would like to tell stories with this interface, to be able to do something participatory, and also tell a story so that the spectator would play an active role in shaping the narrative. As it happened, we did our first residency four years ago at LabLab in Villeurbanne [21] (a suburb of Lyon). That’s when we started to use this tool to tell a very short story: the coming to life of a digital anomaly. It was a very short 15 minutes tale, maybe even shorter. It took us four or five days to put it together. At that time, there was no tale yet. There was just a text projected on the screen, as with subtitles for a moving image. The public would draw things before entering the performance space, for example stars. In fact, what we wanted to test was the different types of interaction with the public, how we could get them to participate beforehand, during the projection, while looking, how to make them stop, etc. This residency helped me a lot afterwards in writing, and particularly interacting with the public. Maxime Hurdequint participated in the creation of the basic concept and after that he was doing the management of the project, publicity, looking for places to do it, he did quite a number of budgets templates, when we had to get people to sign, etc.

16. Delphine: Two Tales

Delphine:

With Julien, now, we present the tale of “Peter and the Witch”, it’s a traditional children’s story. I mention this one because it’s very rhythmic, between what I say and what he plays.

The Tale of Peter and the Witch

|

In a village, there is a witch. |

Delphine :

There is also

The Tale of the Gingerbread Man

|

It’s the story of a gingerbread man made by a woman, she puts him in the oven, and he escapes through the window, runs away, runs, runs, and everybody is running after him, and he runs, runs, runs. And the fox, he is waiting for him at the other end, he entices him with big praises, so evidently, he trusts the fox. He gets on his back, and the fox, “crrrr”, eats him. (At this moment, we have to be together, when he devours him.) “Crrrr, hop!… He’s eaten him!! |

Delphine:

So, Julien and me, we have some very well synchronized cues between us. He performs very near me, we know each other very well, he knows how I tell the story, so, we can improvise things together. We work a lot together face-to-face, even though we also do a lot of work on our own. I can give him the story that I want to tell on paper, or in a book. He brings his own stories too, and he says: “Ah! I’d like to hear that story, I think it’s cool, and plus I’ve got a musical universe for it”. I work a bit on my own, and he work a bit on his own, about roughly what we want to do. And then, we work on getting things in place. And we say: “Let’s do it!”

17. Origin of the “Tale of a Common Future”

Scene 1: The telephone rings at Delphine’s home. It’s Louis Clément

|

Louis: My name is Louis Clément. The association Antipode gave me your name. I would like to do a spectacle in which you imagine how it would be in 100 years, but in an ideal world. Delphine: Ah yes! No doubt about it, we are in this ideal world… Louis: 100 years from now, it’s been done! Delphine: OK, and how did we get here? Louis: I often tell stories, I’ve got the knack for it, I’ve done it with lots of students, because I participate a lot in artistic and cultural education residencies, and what I often talk about is trying to change the world on my own scale: again, it’s utopic on my part, but then it’s something which carries me along. How can I change the world? I can’t invent very cheap renewable energies, I can’t invent a totally carbon-free means of transport of the future, as for example the cargo-bike. So, I thought that I would just like to get people to reflect on their future and above all to try to go in the opposite direction to everything that’s a dystopia, to try to start with something where, basically, you think about a future in which everything goes well, and how is it possible to achieve this.. Delphine: What you say does me good. Because at the moment I’m in the dark, immersed in punks’ stuff, in things where the world is… Sometimes I think I’m going to throw a bomb on this world, I mean, we’re going to blow up things, when you realize what’s happening in the world, it’s just “aaaah!…” Sometimes, it seems that there are people to kill, there are things to blast, anyway it’s got to stop, period. I hang out with the world of punks, no future. Louis : Through my reading, I got a lot of inspiration from stories telling us that basically it’s thanks to thinking that you achieve to do things. In particular Neal Stephenson, who is science-fiction author I quite like, who developed a theory called hieroglyph theory: it has to do with technological innovations, and thanks to science-fiction you are able to make major technological advances. His favorite example is the fuel for rockets, he explains that it’s a science-fiction novelist who said that it would work in such and such a way, and then afterwards, a researcher started to work on this idea using this writer’s intuitions and succeeded in creating the first rocket fuel. I like to tell this story to the students I work with or to the public, I like to stress the fact that, basically, if you want to move towards a desirable future, you need to think about it first. So, the first stage to having a world you want is just to reflect on it. Delphine: In fact, it’s cool to imagine this, it counterbalances the dark ideas. OK say that in 100 years we will be in an ideal world, and you do everything possible to get there. It’s not a question of criticizing everything that’s wrong, of pointing the finger at what doesn’t work, even though you know so many things that are wrong. No, we’re going to say, OK, in 100 years’ time we’re in a cool place. So, OK. I don’t know what I’m getting myself into. Well, yes, I’m interested. Louis: Well, you’re interested, go on, let’s do it.. Delphine: But you don’t want to see what I am doing beforehand? I play at the media library in Mâcon, on such a date, for children and in the evening for the general public. Louis: Ah! I cannot in the evening, I will come at the performance for the kids. |

Delphine:

So, Louis came to see my Jabuti performance at the Mâcon multimedia library: a trapeze performance, actually. We put the trapeze back on, because I’ve got a friend who is also trapezist. I’ve got a circus network around me. Jabuti was a spectacle of storytelling-trapeze-flute. It was a stroll: we went strolling with the public around the media library and led them to the trapeze. So, he came to see the performance, and that’s how we met for the first time.

Louis:

So, that’s how we crossed paths. Anyway, I arrived a little early before the performance, we had a chat, I explained the project, how it will happen, etc. After that, she presented her project, I had to go back to Lyon before the end of the performance, so I didn’t have time to debrief at the end.

Scene 2: New telephone call from Louis to Delphine.

|

Louis: Hello, hi.. Delphine: Hi. Louis: I saw your performance, which I thought was very good. So yes, it’s fine with me, if you are still willing to do it, OK, let’s do it. Delphine: OK, let’s do it. Louis : Let’s go. |

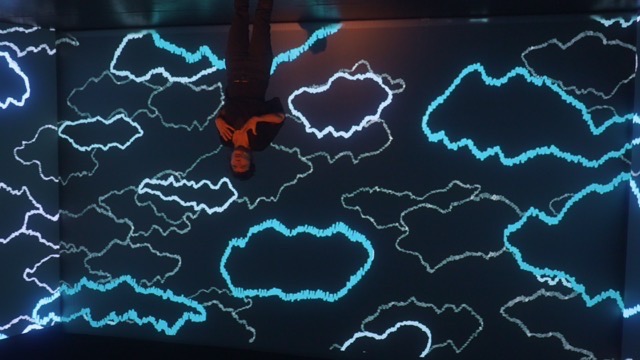

18. The AADN Immersive Project

The project of the Tale for a Common Future was initiated by Louis. It was his first real spectacle, he had at first few ideas that were still brewing, he knew what he wanted to do but he had difficulties putting his ideas into concrete form. So, when we started talking about it, he had in mind a first team and above all he was looking for funding, in any case, so that we could get places to enable us to create the immersive aspect of the spectacle. A first proposal was put forward, it came close, but it didn’t work. Then, once we got the funding from AADN for this immersive project in planetariums, let’s say in certain towns in France, we started to talk about writing the spectacle, because it was about one year before the first performance.

Maxime:

It started that way. Louis had the intuition to bring us together. In 2019, we organized a residency to try to tell a story using Live Drawing. We made a 5-minute piece, with very, very simple graphics, frankly, it was great. Telling stories became a possibility, but at this point we didn’t go any further. It gradually germinated along the way.

Louis :

And then there was the call for proposals by AADN (Arts & Cultures Numériques) [22] – I was a benevolent member of its Executive Board. They launched a call for immersive creation. It interested me a lot because I started going to see immersive full dome spectacles, and I thought it was pretty crazy, well, it was rather amazing! The immersion that was felt in front of these images aroused my interest. The AADN point of view was to bet on collective immersion, that is to get many spectators to participate in an experience, rather than to have an individual immersion as in virtual reality (with headsets). I liked the idea of going against individual forms of immersion. We’re talking today of the « Metaverse » [23] it means that it’s either about immersing yourself individually in a collective thing or it’s about collectively immersing yourself in a work: you’re all together.

Maxime:

So, it’s Louis who really comes up with the concept, he knows already what he wants to do, and who he wants to work with. We found a first storyteller, but in the end, we didn’t necessarily get the grants we wanted, so we ended up finding a second storyteller, Delphine, and Louis had already found Yovan for the music, who he knew very well. And we got the immersive grant in 2021.

Louis :

We answered the AADN call for projects, I don’t remember the exact date. I took a certain number of decisions: I started by telling this story, I came up with the name of “A Tale of a Common Future”, in retrospect, I think that it speaks to a lot of people. After a first refusal to our proposal for the AADN Call for immersive projects, we resubmitted a project. And this time we got it and the AADN agreed to take us on as a delegated production, which meant that they’d help us raise money and to get performances. And from that moment we have to produce written proposals and start the residencies. I’d been working with Maxime Hurdequint with the Live Drawing, we couldn’t do without his drawing skills, I asked him to make the sets. I thought that a musician was needed, so obviously I asked Yovan Girard, whom I admire a lot, he made a lot of music with a sensibility that I like. He usually composes strictly musical pieces, but he had already done a theater piece with someone. I know he can do it too. We’ve known each other since early childhood, my parents and his parents are very close friends, my mother and his father went to high school together, I think.

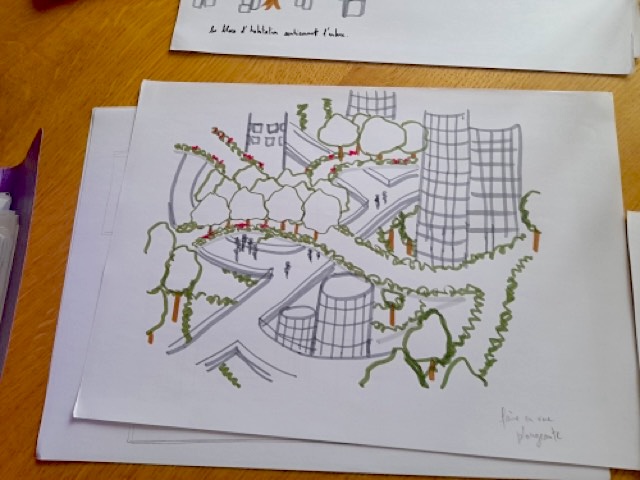

19. The “Tale of a Common Future”

Louis :

So, I set up a calendar for creative actions, we decide on dates, we start doing things together, etc. I continue in parallel to seek more fundings on my own. While this Call to immersive projects grant brings us some money, it’s not enough to pay everybody all the time, and what’s more, I ask people to work outside the residency periods. We’ve submitted I don’t know how many applications to various organizations. For example, we submitted three times a proposal to the Hybrid Creation in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes before getting something from them, and also we applied to the CNC (Centre National du Cinéma) and we were successful, as a result we obtained a substantial amount of money. Thanks to that I can breathe a little easier, because I’ll be able to pay people properly for their creation, this is for us a great chance.. And then, we also got some funding from SACEM (music author’s right society). And we were able to do another residency, at the LabLab, and to pay the Enghien-les-Bains Centre des Arts residency, that was not otherwise renumerated. This residency lasted two weeks, because the place by chance was available. They would provide the place, but that’s all, they didn’t do any co-production, they didn’t give us any money for that.

Before finding the title of the “Tale of a Common Future” (Conte d’un futur commun), I was thinking that the reactions of the public should be able to inflect the story’s unfolding. If it was written, we would have arborescent scenarios, with multiple choice trees, this was going to be potentially very complex. And then, there was that idea of a story told around a fire, with people participating, that kind of thing. What pleased me was the opposition between the tale as one of the oldest forms of “art” with its manner of telling stories, and the participatory side, the smartphones, the projection, you had to find a balance between the two. So, I decided that it could be a tale.

Delphine, Maxime, Yovan and I started to work together on this project. I really had already the whole universe of the tale in my head. The first time Delphine and I met, I had the whole unfolding of the story. I knew where it starts, what you are going to see, and how it all ends. In fact, I didn’t really know the storyline, but the places where it happens.

20. Louis, One Year to Reflect

Louis :

For a year, practically nothing happened, there were no meetings or anything else. I was thinking on my own, in a rather introspective way. Nothing specific was emerging, but I read an enormous number of books, no longer just for “pleasure”. I made a huge list of works to read. These are all references to concepts, people, thinkers, projects that inspire me, from people who would talk about how they were writing about this topic.

During this year of thinking about the project, when decisions had to be made, it was all in my head, at no time had I written down anything. I formalize things in my head, I just say to myself: this is going to be like that, we’ll start there. And then there was this idea of going to visit places where there are communities living in harmony with their environment, and that, in fact, cannot be done in a hurry: one would do a complete tour of the environment, in the forest, the mountain, through the airs, under the water… And then, I thought, on account of their importance, the city should be a big thing, which will not disappear, so we needed to find an interesting way to inhabit this town. I read a lot of stuff on re-wilding in fashion, like Baptiste Morizot [24], all those people speaking about how to give back a place to nature in the city.

21. The writing of the Tale, Louis and Delphine

Louis :

With Delphine, we meet a first time for two days. At the beginning, I come with my story, but in fact I really have only the places of action, and Delphine is the one who’s going to knit everything together, the relationships between the characters, how they are going to be, how they’ll talk to each other, and that helps me a lot. I present my ideas to her and how they might be developed: I want the heroine to go there, and there, and there…

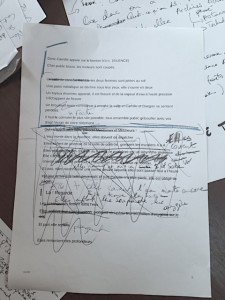

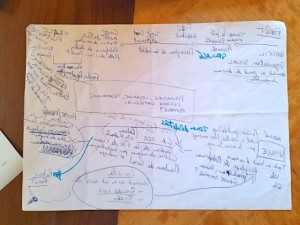

Delphine:

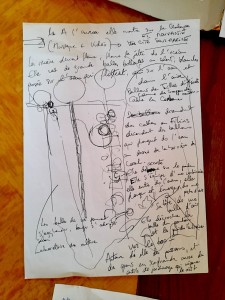

I draw, I write, and then, on my own I go over it again, I reimagine what it looks like, and I find a way to say it. And then, when I’ve found it, I can fix it on paper, and I put the texts on my computer. But after that, I keep modifying them a lot.

Photo: Nicolas Sidoroff

Delphine :

That’s why I have lots and lots of texts on my computer. When I am working in the residencies, I need to have written papers that I cross out, that I correct directly, you see, for example here, it’s all corrected. I am lost if it’s too much a shambles. It also has to be clear in my head, that’s why I write a lot of texts. Writing the tale starts always with paper, because I’m in the habit of writing by hand. Louis is on the sofa and says to me: “OK.”

Scene 1: the first working session between Delphine and Louis.

|

Louis: OK. Let’s start with the arboreals. Delphine: We need a heroine. Louis: There’s the question of whether it should be a girl or a guy. Delphine: Neither, as far as I’m concerned. Louis: Should we use the principle of saying “iel” [he and she at the same time in French.] Delphine: For me, it’s a little complicated to put in place, because of the conjugations behind it and the understanding by the audience is a bit tricky. I read books which use “iel”, which means “he and she”, in order to avoid having a feminine or masculine character. Many feminists use this formulation. It’s complicated when you have a public that doesn’t know, children, for example, you say “iel” and they are not going to understand. Louis: We can decide that it will be a girl. Delphine: Yes, but with a name that can be applied to both genders. Instead of using he and she in the text, you could use the first name of the person. Louis: I propose Camille. [25] Delphine: I agree. Louis: I’ve got all the places we’re going to visit: arboreal, after that the city, after that the coral, … I’d like Camille to go over there, over there, and over there and I don’t know where Camille’s going to go in the end. Delphine: We could add the idea of « magnets » (compasses) that people go to see to determine who are the ones who heal. And also, prairies, plants, and it could end up underwater. Louis: There’s this idea of the Great Council that’s probably located in the city Delphine: I’m noting everything you say spontaneously on paper and keeping it in a file. I keep everything in bulk, even the things we’re going to reject in the show. This is the pile of the entire « Tale of a Common Future ». You see, it’s a mess! Some of the sentences are very clear, I write them down because they seem right to me, I sometimes found them orally. Louis: I describe where it will take place, what we want to happen, where it’s going, and what can be found each time, and you, you’ll transform it all into a story. It’s you who will write the text, the major part of the story. Delphine: I note : “Forest, going through the forest. The train station. The village. The city. The grassland.” I propose to have the grassland before the sea. And then, at the end, that Camille doesn’t return home. We have to find something that involves the audience, that make them evolve throughout the performance, so that they come away from it as though they’d been on a journey. I want people to come away shaken up, that they could say “we went on a journey to a world unknown to us”, a world that brought back some memories, that made us ask questions about ourselves. Louis: What I like is this idea of an initiation rite, it’s an initiation journey. Delphine: You see that I’ve even annotated the body positions: am I facing the public? Do I turn around? We can also work on the stage directions, it’s also an important dimension. |

Photo: Nicolas Sidoroff

Scene 2: the same, a little later.

|

Delphine: In this scene, Camille goes down into the submarine city. Louis: Yeah, you see, we could have bubbles floating outside and then there could be cables falling into the water. Delphine: I’m drawing it. |

Photo: Nicolas Sidoroff

Scene 3: the same, biocracy.

|

Louis: Concerning climate control, it’s the idea of piercing the clouds to make them rain. Delphine: You see, “technological solutionism”, I know I have to put it somewhere, but I don’t know where. They are like that: biocracy. Louis: Somebody who really inspired me about biocracy was Camille de Toledo [26]. I went to one of his lectures, “The Witnesses of the Future” as part of the European Lab. In fact, what I really liked in this, was that he was talking about a future where people were going to ameliorate the world all the while changing it. I was really touched by the emotional side of this. Additionally, it was something easily feasible in the world we live in, that is, it was to decide to give nature the rights to be represented as a legal entity in the same way as a corporation. Basically, this gives to nature the right to sue people who destroy it. I found that very clever because it’s something that rests on something really quite minimal. We always tend to think that you need to make enormous changes in making the world move. And in fact, no, it’s really only the small details that count, thanks to a system that already exists, you can change the world. Delphine: Camille de Toledo, here he is, he imagined that in the future, there would be houses that would have been destroyed in order to make zones of carbon rain. Then, the people who were not happy with this would take it to court. This story is very moving to me. There is a kid who says: “My father came back crying, he had tears in his eyes, and I wondered why he was crying like that, why he was so sad, what happened?” In fact, he was crying from joy, and he said: “The bees are no longer dying, if the bees stopped dying, it means that we are on the brink of achieving what we want.” He imagines that there’s been a real change, about women too. Camille de Toledo is the one who gave us the idea to launch all these lawsuits: lake Annecy against the owners of the lake, the Danube against the Vienna town hall, the North Sea against the Russian tankers, the Upper Mediterranean against the Suez Canal, the Primary Forests Association against the coal producers. It was also important to me to speak out, even if it got me back into the not-so-cool stuff. It’s true, when you get back into it, ouch! you say to yourself, that just isn’t acceptable! Louis: Well then, I find that perhaps what you said is a little too negative, it implies that there’s something negative in this world, in this perfect world. “Perfect” here is in quotation marks, it’s not perfect but it’s a desirable world. |

Scene 4: the mudslide

|

Delphine: Then, what is our heroine doing there? What’s happening to her? Above all, what is the basis of the technique? Louis: You write, you use up a lot of paper, you’ll write a lot of things that in the end will not be included. Delphine: We don’t have an ending, we’ve got nothing, we’re off on something whose beginning we know, but without knowing where we are going. What causes Camille to leave in the end? Louis: A mudslide. Delphine: A mudslide isn’t obvious to me as a resolution to the problem of the end. Louis : Well, we’ll chose that anyway, because it seems to be most fitting. |

Scene 5: the propel stretch.

|